The Politics of Science

...in the United States we know that the public opinion polls show that a large majority of Americans do feel that we need to have meaningful action on climate. Probably about 70% according to most polls, and yet there seems to be relatively few consequences at the polls for politicians who don't do it.

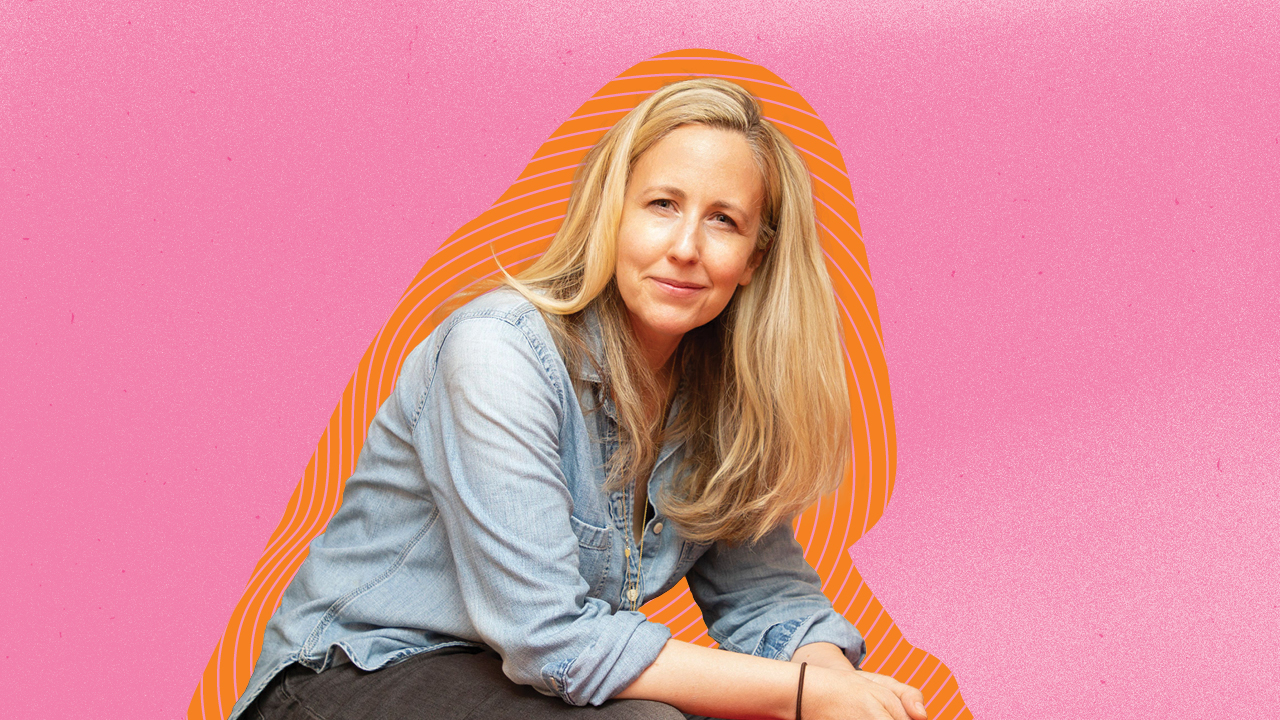

More than anyone, Naomi Oreskes understands the politics of science and how public understanding of science is created. In her 2010 book, Merchants of Doubt, the internationally renowned geologist, scientist, historian and author drew several parallels between the tobacco industry’s denial of science, and similar tactics used by the fossil fuel industry to create uncertainty about human-induced climate change.

Now, in her latest book Science on a Mission, Oreskes looks at how military funding has shaped what we do and don’t know about the oceans.

Hear Naomi in a conversation with UNSW climate scientist Matthew England, as they explore the enduring challenge of what scientists can do to maintain public trust in their work, and how the community can be more discerning about what they choose to believe.

The Centre for Ideas’ International Conversations series brings the world to Sydney. Each digital event brings a leading UNSW thinker together with their international peer or hero to explore inspiration, new ideas and discoveries.

Transcript

Ann Mossop: Hello, and welcome to the Centre for Ideas podcast, I'm Ann Mossop, director of the UNSW Centre for Ideas. The conversation you're about to hear, The Politics of Science, is between scientist, historian and writer Naomi Oreskes, from Harvard University, and Matt England from UNSW Sydney. It's part of our International Conversation series, where writers and thinkers from around the world join leading UNSW researchers, to explore new ideas and discoveries. Our host tonight is Scientia Professor Matthew England, from the Faculty of Science at UNSW Sydney, where he's also the academic lead of the International Universities Climate Alliance. An oceanographer, Matt's research looks at large scale ocean circulation and its influence on regional and global climate from the tropics to Antarctica.

Matt England: Thanks, Ann. I'd like to also start by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which UNSW Sydney sits. I pay my respect to elder's past and present. So welcome everybody to this conversation with the wonderful and brilliant Naomi Oreskes. Naomi is a leading voice on the role of science in society today. Naomi Oreskes is a professor of history of science at Harvard University, where she also holds an affiliated professorship in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Naomi is well known as a columnist in Scientific American, where she talks about the role of science in society, climate change, politics, and all sorts of issues that we'll get onto later on this evening. She's also the author of many books, including Merchants of Doubt, and Why Trust Science? Naomi, it's great to see you again.

Naomi Oreskes: Great to see you. Thank you, Matt.

Matt England: So I want to start actually, by going back to early in your career, it really fascinated me when I learned that you actually, were a mining geologist for some time there, you worked in Australia. So I want to start by asking you, you know, what got you interested in science to start with and geology in particular, and what was it like, working as a mining geologist in the outback of Australia?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, I was one of those kids who collected rocks and bugs, and just always liked being outdoors. And so geology was a field where you could be outside and still do things that were intellectually interesting and stimulating. And you could travel the world and all of my mates from university all went and worked all over the world, in all kinds of different places. And so I landed in Australia, and I worked for Western Mining Company based in Adelaide, and working out in the bush at what is now Roxby Downs. And it was a great experience. It was amazing. It was different. I was the only woman geologist on the staff, certainly, times have changed for the better in that respect. But it was a great experience. It was so exciting to be working on a project, on an ore deposit, that had been discovered, but really wasn't understood. And it was a quite complex and confusing ore deposit. And it was a reminder that there are a lot of things about the world, we still don't understand. I sometimes feel as if all the big questions in science have been answered. Or I remember I had a mate who worked for a different company who said that he could remember sitting around a campfire in the northern part of South Australia, and people saying, oh, all the big ore deposits have been found. And about a year later, you know, Roxby Downs was found. So it was a reminder that the world is exciting and complicated. And what makes science great is that we discover things we didn't know about before. And we learn new things every day, and that was a great experience. Great way to start a career.

Matt England: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, earth sciences, I mean, oceanography, atmospheric sciences. It all involves studying our planet. And that involves going to remote places sometimes and, and trying to dig up stuff or dive deep into the ocean and measure things that haven't been measured before. It's a great field to be in. But then I'm interested too, that you then moved into, not just being a scientist, but actually studying how science works, you start to think about putting forward hypotheses, dissent and disagreement, you know, what constitutes certainty. Now, what made you start to think about the history and philosophy of science, if you like, rather than just being a scientist?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, I think there were several things, I was always interested in what you could call the bigger issues around science. And I was always interested in history, the arts, literature. So as an undergraduate, I had a really hard time deciding what to study in university, because I had these interests that people told me didn't go together, like history and science. So it was sort of exciting when I discovered that actually, they do go together, but also partly the experience of Roxby Downs. Because we found this ore deposit that didn't fit into people's standard models of ore deposits, and the rocks we were drilling, which were all under the surface, there was no surface exposure. So the only information we had was from drill cores and geophysical data. And these rocks, if you go to college and study geology, you're taught there are three kinds of rocks igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. These rocks were none of those. And we had big fights actually about what it was we were looking at. And the geologists who first started working on the project, thought it was one thing. And then a group of younger geologists of whom I was one, we thought it was something else. And it was actually really hard to say that, because the social structures and the social hierarchies in the corporation made it hard for the junior geologists to speak up. And so it was a really early lesson in the social dynamics of science, and the ways in which social dynamics influence what we see, what we think we see, how we interpret what we see and what we feel we can say. And so that early experience was really formative for me in trying to better understand how it is that scientists actually come to conclusions about the natural world and how we make sense of the things we're observing, especially when they're unexpected.

Matt England: I think it's impressive, you stepped back at that stage in your career and thought about those things. You know, I think a lot of scientists, we bury our head in the test tubes and the microscopes, and we want to discover stuff, and stepping back and thinking about that process of validation, and so on, again, in your work through I mean, obviously came out of a conflict that made you thinking about that, trying to get your ideas through. But, you know, do you think that scientists need to keep stepping back from their work like that, and thinking about how they, you know, get to, you know, establish facts and claim something certain. I mean, we often hear people say, science is never certain. But I think that's not the case at all. There are fundamental laws of physics, and we… sometimes I think scientists don't speak enough about those facts, because we are working at the edges of uncertainty.

Naomi Oreskes: Well, absolutely. And I think, you know, a lot of times people think of certainty as a yes, no proposition, you know, zero or one, either it’s certain, or it's not. But of course, it's really a spectrum, there's a very wide range of degrees of certainty. So there are certainly things in science that we know, beyond any reasonable doubt, and that are extremely unlikely to change in the future, then there are other things where we're really quite confused. And it's important to be honest about our confusion, because we can't learn new things if we pretend we already know all the answers. I think, for me, really my whole career since that early experience has been about stepping back. And it's been about thinking through, why do we study the things we study? How do we study them? Why do we decide that certain kinds of methods are better than others? And how do we judge evidence? And what do we do when we have disagreements among ourselves about evidence, and so really, everything in my work is about that stepping back. And I definitely think that science would be better off, if more scientists did that. Because there is tremendous pressure, because science is competitive. There's tremendous pressure to sort of charge ahead and not look right and not look left. But sometimes we really need to step back and think about these larger questions. Otherwise, you know, we plough forward and we make mistakes. And then that's when we end up with mud on our face, and that's when people say, oh, but you got that wrong. And then scientists get all perplexed because they don't know, they don't know how to answer those questions about, well, what do we say when we make mistakes? Because when people and we do, in fact, make mistakes.

Matt England: Right. That’s really well put, I mean, in a way the establishment of that scientific understanding is this process of actually building upon knowledge. It's sometimes those mistakes that actually lead to the discoveries later on, they can be really important in that process. I want to talk a bit about people running headlong into discovery. This wonderful book you've written, Science on a Mission, I was really blown away by the amount of detail you dug up. It's a book, charting the history of oceanography, in particular, in the United States, post World War Two, it goes through what the navy funded in terms of oceanographic research, and in some cases, the scientists were opportunistic, and took that funding and, and tried to make curiosity driven discoveries. They wanted to understand the system they were looking at, in other cases, it muddied the water to have that funding from the navy. And so do you want to talk a little bit, Naomi, about what got you interested? I know you're at Scripps for a while. And so that possibly was the start point. But what drew you into that topic, the Oceanography in that cold war era?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, there were two things and one was intellectual. Yeah, that was practical. And I always think it's good to talk about the practical stuff so that young scientists and historians know that it's okay to have practical reasons for doing things. So the intellectual reason came out of my early work on plate tectonics. So my PhD dissertation and my first book was about the development of plate tectonics, and particularly about the contrast between an early debate that had taken place in the 1920s over the theory of continental drift, which was mostly rejected by scientists and then contrasting that with what happened about 30, 40 years later, when the debate gets reopened, and scientists conclude that yes, indeed continents do drift and continental drift theory gets mobilised as part of the larger plate tectonic theory. So that was a really important study for me, because it was an example where you could actually look at two different debates and say, well, why didn't scientists reject this idea in one case, and accept it in another? So we don't have controlled experiments in history. But it was close to a controlled experiment. And one of the things that came out of that study was that the debate gets reopened when there's a new body of evidence. And that new body of evidence comes mostly from the oceans. And it comes mostly from work that is funded by navies, particularly the US Navy, but also the Admiralty in Britain. And so I became interested in well, why was the navy so interested in the deep ocean? How did that come to be? And why did this evidence become available after World War Two, which had not been available before? Because scientists were always curious about the ocean. It's not as if scientists suddenly woke up one day and said, oh, we should really be interested in the deep ocean. No, I mean, scientists have been interested in the deep ocean since the ancient Greeks, but they didn't really have the capacity to study the deep ocean until they got help from navies and help both in the form of ships and also money. So that led me to have this interest in oceanography, how did 20th century oceanography develop? So that it developed this capacity to study the deep ocean, which I mean, oceanography, you know, is older than the 20th century, obviously, they were great oceanographic expeditions in the 19th century. But they didn't, they weren't able to study the deep ocean very much. So I got interested in that, and that became the idea for a book about deep sea Oceanography in the 20th century. But in addition, as you say, I was living in San Diego, teaching at the University of California and at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. And I had two young children. And I really needed a project where I could go to the archive in the afternoon and still be home for dinner. And so that combination of a big intellectual question and just a really practical place to do my work at a time when I had a young family, those two things came together in a really, in a really helpful way.

Matt England: Yeah, no, nice. And thinking about what you just mentioned, in terms of deep sea oceanography, it's a very hard place to get to. So isn't it a good thing, the scientists of the day, in a way hitched a ride on the navy probes and on the navy vessels? It was opportunistic, as you mentioned in the book, but I mean, was it a bad thing that so much of this oceanography came from… what complications did it create for that community?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, it was both good and bad. And that's really the argument of the book that there are trade offs. So the good part is what you exactly just said, that the navy… navies support both in terms of equipment, ocean going vessels, deep submersibles, and also money, funding, made it possible for scientists to study the deep sea in a in a way that it had never been able to do before. And so in that sense, the navy support was greatly empowering. It was really enabling, it enabled scientists to do things that they simply would not have been able to do, had they not had that support, and a lot of really big scientific questions about deep ocean circulation, about life in the deep sea. And about plate tectonics, were answered in that time. So it's an extremely productive period of scientific work. And that's partly why I was interested. I wanted to understand this period of really great scientific productivity. But, and here's the but, was the trade off. So most of the scientists who worked in that period, and many of whom were still alive when I started this project, so I was able to talk to them. They all talked about this as a really great period, a golden age of oceanography. But what they didn't talk about or what they got nervous when I asked about, were all the things that didn't get done. The questions that didn't get answered, things people were interested in, but couldn't study, because the navy said, that doesn't fit the mission profile. And what we see in this study is that the navy is very clearly defining certain things that absolutely interest the navy, and the navy is absolutely willing to empower scientists to do those things, and the scientists who do them feel empowered, and they would say, oh, the navy's not telling me what to do, the navy has given me all this freedom. But also other scientists who want to do other things, and are actually in some cases told no, you can't do that. Or discouraged from doing it, or there's simply no money to do it. And what I argued at the end of the book is that that has real consequences.

Matt England: The history of oceanography, right back before this period is sort of steeped in geopolitical opportunities, if you like, you know, early colonialist voyages across the ocean, were some of the first measurements and even today, geopolitical or navy based funding, you know, sets the agenda sometimes. I know, in Australia, we've got a big Antarctic Survey going on. It's not the way the scientists would do that survey though, so it's a really tricky issue. Opportunities there, but I do hear what you're saying, it can be tarnished, it can be restricted in ways that the scientists, you know, that their science has held back. And if you have a big airport built on Antarctica, for example, for a geopolitical reason, and the science that's undertaken there, is nothing compared to that funding being spent in other ways, then it's clearly bad for science and scientific knowledge.

Naomi Oreskes: The main argument I'm making is not so much to think of navy funding as being bad. As to think of it as being limited. That it has certain constraints, as everything in life does. And so really the book, in a way, is an argument for diversity, diversity of funding sources so that we don't put all our eggs in one basket and neglect other potentially important questions that also need attention.

Matt England: Absolutely. It did get me thinking when I was reading the book, the way the NSF, the National Science Foundation, for example, in the United States, or the Australian Research Council here in Australia, these funding agencies that do support that pure, curiosity driven, blue sky discovery research is so important. Do you see issues there in terms of, I mean, over the years, the NSF has been, you know, cut back and then sometimes boosted in funding? Is there a trade off between the two?

Naomi Oreskes: No, not necessarily. I mean, if anything, I think, I mean, it's hard to generalise. But I would say in the 20th century, they kind of went up together in the United States. So I don't think it's a trade off in the sense that there's a finite pot of money. I think it's more a trade off in the sense that if there's an ample source of funding from a particular patron, scientists are going to flock to that, because they say, look, there's all this money here. And we see this, I mean, every time there's a crisis in the world, whether it's COVID-19, or September 11, you see scientists flocking to move into that area, because they see support. And it's a totally understandable thing, because without money, you can't do anything, right? But I think the scientific community as a whole, has been maybe not as sensitive as they might be to what some of the costs of that are, some of the losses. That if you flock too much to glom on to a deep pocketed patron, other things are going to get missed. And it's not so much a question of basic or applied science, because the navy did fund a lot of basic science, in areas that were of interest to the navy. But what they didn't fund were areas that were not of interest. So it's not basic versus applied science. But it's really about what are the driving missions of the institution that's funding the science?

Matt England: Absolutely. When you say that I'm reminded of a different institution funding science that goes towards your book, Merchants of Doubt. And it's a very different topic. But I want to go too quickly, if we can, you know, this ExxonMobil research in the 70s. Back in 1977, they did the early calculations, kind of in parallel with the early calculations from the scientific community of what greenhouse gas emissions would do to our planet, they had predictions of how things would play out, that are now decades old, we've seen 40 or 50 years play out since that research was done. And it was all very accurate. And yet, it took 40 years for that to be exposed. And that’s a terrible example of now funded research from, in this case, of fossil fuel, big emitter, discovering something, and sitting on it, in a way keeping it secret. Is that the case with that research? It was kept under lock and key when it was first produced?

Naomi Oreskes: I don't think it was exactly kept secret. I mean, we actually… my research associate and I, Geoffrey Supran, have a new paper coming out on this, hopefully going to come out very soon. It's not so much that they kept it secret. I mean, actually, ExxonMobil has tried to accuse me of accusing them of suppressing science. And that's not my argument. It's more about what I call the context of motivation. What is it that motivates scientists to do work? And that can include motivating the funders, right? And so what we see is that in the early period of the climate change research in the 70s, and early 80s, ExxonMobil was quite motivated to better understand this problem, and to think about how climate change was relevant to their business model. And we see them funding good scientific research, and we even see some of that being published in peer reviewed journals. But there's a point at which they begin to realise that it's actually really bad for their business model, and that they have a really big problem. And around that time, around 1988, 89, we see them shift gears very dramatically, and cut off this very interesting research program that they had funded internally, and move into the space of climate change denial. And so this is really important, I think, for scientists to understand because I'm not saying that corporate funding of science is necessarily bad. The private sector has funded great research in many areas of life. I mean, there's a long history in the United States of corporations like General Electric, Westinghouse, Eastman Kodak, I mean, Eastman Chemicals funding, really good scientific research. But one does have to think about, what is the motivation? What are they trying to achieve? Because what we see in the ExxonMobil case, is that when they start discovering things that are bad for their business, that's when they stop funding the science. And then, and if they had just stopped funding science, I would say, well, okay, I mean, that's the right of any private corporation to decide if they do or don't want to fund science. That's not really the problem. The problem is that they move into the space of disinformation.

Matt England: Yeah, absolutely. And that's a great point to talk about. Your very famous book, Merchants of Doubt, published in 2010. Came out as a documentary in 2014. And there's a new edition around 2020, I think. This was an amazing piece of work. I want to start though again, asking you, you know, what was the genesis was the very early part of that book, what got you interested? What came to you as a revelation, if you like, for starting that book?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, that book was an accident. I never set out to study disinformation. At no point in my life did I ever say wow, disinformation is a really interesting topic, someone should study it. No, quite the opposite. I was working on the history of oceanography, and the work on the history of oceanography had led me into the early work that oceanographers like Roger Revelle and Dave Keeling had done on the issue of climate change. And in doing that work, I found myself surprised to learn how deep and how extensive the oceanographic work on climate change was, and then it went back to the 1950s. And so I started to become more educated about the current state of climate science, this was in the early 2000s, and to realise there was a big gap between what the scientific community was saying about climate change, which was that it was happening, that it was already underway, and that it was absolutely being driven by greenhouse gases and deforestation. And that there was really no debate about that, versus how it was being presented in the mass media and by politicians who were presenting it as a great debate. And I was naive enough to think that the politicians and the journalists were just uneducated, that this was a problem of the public understanding of science. And in my own defence, I would say, I think that's what everyone thought it was then, it's certainly what all the scientists thought. That if we just explained the science better, more clearly, less complicated graphs and charts, plain English, we could explain this and everybody would understand, and then we would get to work on solving the problem.

So I did a little analysis on the state of the scientific knowledge and the state of the scientific consensus just to kind of double check my own impression. So my impression was that everyone I knew thought climate change was real and underway. There didn't seem to be any big debate when I went to, let's say, scientific meetings, like the American Geophysical Union. But I wanted to check that because you know, our impressions can be wrong. And so I undertook an analysis of the peer reviewed scientific literature asking, how many papers – published papers – disagreed with the conclusion of the IPCC, that most of the observed warming was due to the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations, and what I discovered was, none. So I published this paper in Scientific Magazine… I now know, in hindsight, that that was the first paper to analyse the scientific consensus on climate change. And in fact, people now credit me with inventing consensus analysis. I'm not sure that I knew I was doing that, but I guess I did. And when that paper got published, I started getting attacked. I started getting hate mail, threatening phone calls. People filed a complaint with my university, and I was attacked by a US senator. And one of the strangest days in my life was when I got a phone call from a reporter at the Tulsa Oklahoma register, asking me to respond to this attack on me by the US senator from Oklahoma. And I remember it was right around the first of April, because I remember thinking, is this an April Fool's joke? Like I truly had no idea what was going on. And so I always say this was my Alice Through the Looking Glass moment, I had walked into the world of climate change, disinformation and denial. I didn't know it at the time. But what I discovered was that this was not a problem of public understanding of science. This was not a problem of scientific illiteracy. This was a problem of deliberate, organised disinformation. And so I started digging around a little bit. One thing led to another, I met Eric Conway, who had independently discovered the same phenomenon with respect to the ozone hole. And he had some notes on it that he had never written up. And so we started comparing notes, one thing led to another, and we ended up writing Merchants of Doubt.

Matt England: And the ozone story was short lived, in a way, because the solution came along, and the agenda to stop the science getting out was… it's multi-decadal, right? This campaign against climate research still goes on today. Nobody denies the ozone hole is there, that we needed to get rid of CFCs to fix it. When I look back on those decades, for me, the biggest surprise is not that these big emitters orchestrated a campaign to keep polluting. That's not the big surprise. The big surprise to me is that it's lasted so long, it's dying out. We can't pretend it's on the decline, for sure. But how did they get away with it for so long? Why would a person on the street trust a CEO of a fossil fuel company, when they speak about climate physics? How did it last multi-decades?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, I think there's several dimensions to this. I mean, one way it worked, and this is something that we documented in the book. Is that the corporations were very smart, they were very clever, and they hired very talented public relations and advertising firms. And they knew… and they modeled what they did on the tobacco industry. And they knew from the tobacco experience that if a corporate CEO stood up in public and said, oh, fossil fuels are great, that that wouldn't pass the laugh test, that we would all know that that was not objective or independent. But if they could find scientists to say it for them, that could be effective. And that's what the story of Merchants of Doubt is, the merchants of doubt, are not the CEOs of ExxonMobil and Chevron and Saudi Aramco, they're the scientists who were recruited to do the dirty work, right? And these scientists were mostly physicists, and they were mostly motivated by right wing political ideology. And so it's that nexus then of the corporate interest and the political ideology, that becomes very powerful, and then that's another part of it. So they don't make the argument by saying, fossil fuels are great, and you should love us, what they say is that, if we restrict fossil fuels, it will threaten our freedom, or will threaten the American way of life. And by making that argument, they're able to make common cause with a whole network of conservative right wing libertarian organisations and think tanks, and then spread the message to places like Australia, where they make common cause with right wing politics in Australia, and make it a political argument, rather than a scientific one, right? And that's a political argument that resonates with lots of people. So if you say to someone, those guys want to take away your freedom, those guys want to tell you what car you can drive and where you can live, and what temperature you can heat your house till or cool it, if you're in Australia, and whether or not you can eat a hamburger, right? And we hear this all the time. That's something that makes people say, oh, well, I don't want that. So they're very clever about tapping into people's anxieties, and tapping into people's cultural commitments, like the American way of life, right? And then there's one other component is that, this is a genuinely hard problem. It's not going to be easy to solve. And so if you tell people, well, don't worry, the science is unsettled. We don't really know we can wait and see. That's a message that lots of people would want to hear. It ties, it ties into what you know, academics call status quo bias, right? Most of us would rather be told, everything you're doing is fine, don't worry. Rather than be told, oh, no, actually, it's a big mess. And we have a giant problem. So if you think who's got the better message? The scientist who says, oh, my god, climate change is going to be a disaster, and we have to make giant changes in the way we live. Or the fossil fuel CEO who says, no, everything's fine, don't worry. Right?

Matt England: It's a reassuring message it's what people want to hear.

Naomi Oreskes: Exactly.

Matt England: And so when you talk about that, it makes me think about today, the tactics are evolving. And so one of the things I see far too frequently in the press is some big new tech technology that's been put forward, big vacuum cleaners, air pumps to suck down CO2. And I mean, the cost to do this just doesn't scale. Do you wanna talk a bit about these new tactics? You know, this one does resonate exactly with what you said before. And we see it all the time. You know, science does come along, you know, the pandemic, eventually a vaccine… quickly a vaccine was found. Science solves stuff. And that's kind of a problem here, because people see the climate problem and think, well, someday, somebody's going to have a silver bullet that just fixes this for us. And that's being tapped into, I think, at the moment.

Naomi Oreskes: Absolutely. So I don't generally like it when academics invent new words, I think it's generally obnoxious. But in this case, I actually have invented a new word because I felt like we needed it. And it's what I call techno-fideism, faith in technology. And I use the word faith advisedly, because it's about a kind of blind faith or an unwarranted faith. Because obviously, technologies do solve lots of problems. But the COVID vaccine is a good example. So it's really impressive what scientists did in developing effective and safe vaccines in a very short period of time. It's a huge scientific accomplishment. And yet we see that new variants, new strains are coming about because we still have billions of people on the planet who are unvaccinated. So unless you solve the social problem of vaccinating unvaccinated people in Africa and elsewhere, new variants will arise. And you will find that even the best technology in the world won't protect you from the disease. Or look at the United States where, you know, 30% of our people are still unvaccinated, not because the vaccine is not available to them, it is available and it's available free of charge. But because they don't want it, because they don't trust it. And why don't they trust it? Well, because some right wing politician has told them that scientists are no good, and you shouldn't trust those eggheads or other things. So if you don't get the social dimension of a problem right, you could have the best technology in the world and you might still not solve this problem. Now, the case of climate change, techno-fideism is a form of climate change denial. It's a way of kicking the can down the road and saying, Oh, don't worry, technology will solve it. Well, I think that in the fullness of time over the next 50 to 100 years, technology will solve it. But in the meanwhile, as we all know, we don't have 50 years to wait, we've already wasted 30 years. So we need to mobilise the technologies that we have right here right now, which is essentially renewable energy efficiency. Those are the big ones. Right. And it is amazing to me, you're absolutely right. I mean, just the other day, I saw a big thing in the newspaper about how the Biden administration is pushing fusion, solar fusion power as a solution to climate change. Well, I think one day, we probably will have controlled fusion energy, but think about it. We have been working on fusion power since 1943. And we have not generated one kilowatt of commercial electricity from it. We do not know how to mobilise solar fusion as a civilian, controllable civilian technology. And we have been working on it for more than 60 years, well, more than almost 80 years now, right? So why would we believe that all of a sudden, this technology is going to work in the next nine years? I mean, there's no plausible evidence to make that case. And yet, we see people… oh, fusion is the answer. And so there's a kind of pathology there, a kind of, I mean, it's almost a kind of neurosis in a way, to deny the problem and to deny the possibility of… I mean, actually, it's a bit of a mystery to me, maybe some psychologists can explain… I mean, why would otherwise intelligent people and because these are intelligent people, keep going back to this sort of, as you said, the silver bullet, the magic technology, that fixes all our problems, when that technology does not actually even exist?

Matt England: Absolutely. And some of the technologies that do exist will create fantastic jobs, economic growth, cleaner air, I mean, there's a whole lot of benefits. And look, progress has been made. I don't want it to be sort of all negative around that, but not enough. And I think there's still this scare mongering can, you know, well, in Australia, especially there's, you know, the message comes out, you know, the mining sector is going to be ruined by moving to renewables. Actually, it turns out, the mining sector is going to thrive with renewables, because there's a lot of, you know, silicon and lithium and other things that need to be mined.

Naomi Oreskes: When I was in Olympic Dam, one of the things I did there was to work on the rare earth element component of that deposit. And everyone at the time said, oh, well, that's just academic, because there's no market for that stuff. And now, of course, the earth elements have become really important. But that's exactly right. And I think, you know, one thing that's important for people to understand, we have really good evidence that we could probably meet about 80% of our energy needs, with the technologies that exist today, solar, wind, storage, grid integration, demand, response, pricing, no miracles required. And yet, somehow, instead of really focusing on those technologies that exist and are available to us right here, right now, you know, we're being told to, sort of, bet the planet on the dream of solar fusion, or the dream of geoengineering. And I think that is a form of denial. And I think some of it does come from the same people who have fostered climate change denial all along, because you have the fossil fuel industry spreading the message that renewables can't do the job, that they're too intermittent. I like to say they say renewables are for sissies, right? You know, and it's a lie. It's a lie, but it's a powerful lie, and many people have been influenced by it.

Matt England: Yeah, absolutely. And some of those fossil fuel companies are the ones funding those grand crazy projects. It's a form of greenwashing, but it's also a form of delaying, reducing our fossil fuel reliance. So just on greenwashing quickly. Um, this is becoming big in politics as well, I think, in Australia our showing at Glasgow I think, was appalling, a few weeks out, a commitment to net zero, and yet the plan to get to net zero is completely absent of any mention of fossil fuel reduction. We've got huge reserves here, we can leave them in the ground. So, you know, what do we need to watch out for in terms of greenwashing? It's not just companies, it's also in politics.

Naomi Oreskes: Oh, absolutely. I mean, it's very convenient for politicians to say that they're committed to solving a problem, but then not actually take the hard steps that would be involved in doing it. So I think the important thing people need to understand is, first of all, this has to happen now, we've run out of time, right? I mean, if we had started working on this, back in 1988, when Jim Hanson first testified in the US Congress, that climate change was underway, when the IPCC was created, or in 1992, when the world signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, we could have largely solved this problem by now. I mean, 30 years is plenty of time to build solar plants and improve energy storage. So we've wasted huge amounts of time, and that's why there's a kind of urgency now, about acting now. And so any proposal that says, you know, we're going to do this by 2050, but we don't actually start until 2035, I mean, that's just not credible, right? Absolutely. then the other thing is the whole offset problem. So the language of net zero hides a multitude of sins. And I would not say that there's no place for offsets, I do think there are some forms of offset that are legitimate and can be valuable in figuring out the portfolio of solutions. But we see that many institutions when they claim that they're going to net zero, and we're seeing this from a lot of corporations right now, we've seen it at my own university, the net zero is achieved largely through offsets, in other words, paying someone else to solve the problem for us, rather than actually making the hard changes at home. And this is deeply problematic, because many of the offsets that are available for sale right now are not verifiable, a lot of them involve forests, where there's no guarantee that those forests won't be cut down 10 years from now, or burned down, or die. So the non verifiability of many offsets is deeply problematic. So I think people have to really be looking closely at the timescales of the commitments, and that their real commitments to stop using fossil fuels and switch to renewable energy, with offsets. I think offsets could be sort of like the cream on top, a little bit of extra help, the sprinkles, but they can't be the main thing, otherwise, it's just not credible.

Matt England: I just want to ask one more question on politics before we get off politics. I mean, in Australia, it's been very risky. To have a climate change policy at some points in the last couple of decades. I think we're now… we've seen three summers in a row of absolutely catastrophic events, bushfires, and then two years in a row of flooding rains that have been so costly and damaging that people are now expecting their politicians to lead. I mean, is that, is that what you're seeing in the US as well, is it politically risky now, to not have a good climate policy? Or… Yeah, what's the status?

Naomi Oreskes: I think it's very hard to say in the United States, because we know that the public opinion polls show that the large majority of Americans do feel that we need to have meaningful action on climate, probably about 70%, according to most polls, and yet, there seems to be relatively few consequences at the polls for politicians who don't do it. And we know that the fossil fuel industry is extremely powerful in funding anti climate opposition. So every time we've gotten to a place in the States, where it looked like we were about to have some kind of meaningful policy, the fossil fuel industry has come in, you know, like a tsunami of lobbying and funding to prevent it. And we also know that climate change is not the only area where the American people support policies that we're not getting from our governments. So it's a very difficult political situation. I think that right now, in the United States, the best hope for action is to work on the state level, because we know that many state leaders are committed to change, particularly large states like California, but also Massachusetts, New York, have a lot of economic power, and are responsible for a lot of greenhouse gas emissions. And one thing I talk about a lot in the United States, you know, we have, and I guess Australia has too, a huge rural urban divide. Like in the United States, we talk all the time about the red states and blue states. But it's not really… the divide is not really between states, it's really between urban and rural areas. Because even in so-called red states, the urban areas are blue, and urban areas are where most people live, and where most economic activity takes place, so it's where most greenhouse gas pollution is produced. And so if you could get cities to act on climate change, you could actually address a large part of the problem. And then cities can become models for states which become models for the nation. I feel cautiously optimistic, because we are seeing some pretty significant changes on the state level. And California AB32, the climate change emissions bill in California has been very effective in reducing carbon pollution. So we know it can be done, we have models for it. But I think we need to talk a lot more about the models. When I go out in public and speak, I find most people have no idea about any of this. We're used to talking about big scale international agreements. But the idea that there's really meaningful things that can be done on a more local level, I think that's a message that we need to get out a lot more.

Matt England: It's like a, sort of, almost grassroots politically, you know, growing from local through to through the state and national. Interesting. I want to change tack just slightly, I want to talk a bit about the IPCC. It's an institute, it's not an institution, it's an organisation that, that I think a lot of us have really admired and been part of, and the work they've done for the last 20 plus years, has been remarkable at overviewing the science, the state of play of the science of climate change, the impacts the vulnerability, and also, of course, the mitigation. And the recent article you wrote made the point, IPCC should shut down a part of its operation. It's done its job, we know climate is changing, we know it's real. Let's get on to solving the problem. Do you want to talk a bit about that? Did you get scientists contacting you up in arms about that idea?

Naomi Oreskes: Of course, and I knew I would and I have to say, you know, actually, I had the idea to write this piece probably fully five or six years ago, after the previous report, and I didn't because I knew that it would upset my friends in the IPCC. But I felt finally, okay, this needs to be said. So here's the thing. You know, I sometimes work as an expert witness in legal cases, and one of the things lawyers will say to expert witnesses, when you get posed a question, answer the question, and stop. And this is something that we all have tremendous trouble doing. And scientists especially have trouble, because we always, you know, we always know there's more to ask, and there's that third decimal place, and there's some detail that we haven't worked out, there's some aspects of the model that's not really satisfying. So it's always possible to keep asking more questions and do more work. But in this case, I think we have to remind ourselves that the IPCC is not a scientific research organisation. It's an organisation that was created with a very specific task, to inform policymakers about the threat of dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system. And under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to which the IPCC is part. The question was specifically asked, what is the level of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that constitutes dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system? Well, we've answered that question. We know because we're seeing it. It's happening, as you said, floods, fires, hail storms, droughts. This danger is now here, it's present. It's no longer a theory. It's a fact. So the IPCC, the scientists involved in it have done their job, they have answered the question that was posed to them. So my argument is they should declare victory, they should say, pat themselves on the back, say, you know, we did what we were asked to do. And how great is that? I mean, how often is it that people in life actually do what they've been asked to do? And then say, and we don't need to keep focusing on the physical science. Because when you do, it actually contributes to the narrative that we still don't really know. And I've had people ask me that question. Well, if we know the answer, why do we need a seven or an eighth IPCC report? Right? So I think it would be incredibly powerful. I mean, think about it, for the IPCC to say, yeah, you know, we actually have answered this question, we're going to close down working group one, which deals with the physical science basis. And we're going to focus attention on working groups two, and three, which focus more on the impacts, the effects, and the solutions, because that's where our attention really needs to be now. How do we help people cope with the impacts? Because, sadly, that's where we're at. And how do we stop it from getting worse?

Matt England: Yeah, no, I think it's a good point. And I know scientists, part of the working group one, who share this view, and I thought it, I think a couple of reports back, I found myself thinking we've nailed this, we know the emissions pathways we need to take and it sends a message, like you said, that we're still trying to work out whether, you know, to what extent this is really happening, and I think it would be a powerful statement, I think, to some of the scientists who think it's not the way to go, it doesn't mean we take away the machinery of the climate model intercomparison project, for example, that puts together the projections, we need those still to play out, we need, you know, downscaling to resolutions that get the working group two sector, the information they need. So it's not about closing that down. It's about that first report, the science of climate change, as you said, very beautifully, it's been nailed.

Naomi Oreskes: I have always assumed that there are scientists out there who agree, but just don't haven't spoken up in public. So I'm kind of hoping that my writing about it, us discussing it, will maybe encourage more scientists to come forward and say, hey, you know, that really makes sense. And it's exactly as you said, it's not a call to end climate science. I mean, there were a group of scientists who accused me of that. And that's just silly. Of course, we're going to keep doing science, but we can do science in our universities, in our national laboratories. We don't need the IPCC for that. But we do need the IPCC to play the unique role that it does play in that interface between the science and the policy.

Matt England: We're running low on time. And I there's been a few questions coming in. And it's been great to talk about all the topics we've had so far. But we've had a couple of questions coming in from the audience, and thank you for those. Some of them relate to your work in Why Trust Science? So another book you wrote, particularly about advocacy, and I'm gonna just give you one of those questions here, if I can. As climate scientists, this is how the question goes, you know, can we still advocate or even join a political movement? Can we do this independently of our research? Is that ethical? The questioner goes on to say that they think it's possible, but the public may not perceive it to be. So what are your thoughts on that?

Naomi Oreskes: Yes, yes, and yes. Scientists absolutely can do this. And one of the things that sometimes makes me sad about science, is that we are very unscientific about these extra scientific questions. So in my experience, a lot of scientists and perhaps the questioner here, assume or believe or think that we will lose credibility with the public, if we become advocates for action. The evidence does not support that hypothesis. We don't actually have a lot of data on this. And so I've actually been working with a really great postdoc Victoria Colonia, who just got her PhD at ETH Zurich. And we have actually published an article on this already. And we're doing some more work, where we're actually asking people this very question, would you find a scientist less credible if they advocated for a policy solution? And so far the data that we have says, no, there are some differences between countries, and we're looking to expand our research to look more. But the evidence does not support the idea that if you stand up and say, there should be a policy action about climate change that that undermines your credibility. And if you think about it logically, why should it? You've done all this great work, the work leads to an obvious consequence, and so now you speak about that consequence. I mean, that's just logical. And this is the argument we made in discerning experts. It's not to say that a climate scientist should recommend, you know, what economic policy should be on inflation, right, because you're not an expert on that. But in the area where you are an expert, it's totally logical for you to talk about what the solutions are that could address that. And of course, that's what the ozone scientists did. And we never came across any evidence that Sherry Rowland or Mario Molina, you know, the great scientists… Paul Crutzen, who won the Nobel Prize for that work, we never came across any evidence that they had lost credibility, either with the public or with policymakers for that. They were attacked by industry, and industry tried to make the claim that they were not credible. So I think it's really important for us to realise that that claim can be actually part of industry disinformation.

Matt England: Thank you, Naomi. And I've got one more question that I had on my list that I want to come back to if I can. Again, I'm obviously reading your pieces in Scientific American avidly. One of the pieces that I was also interested in reading was your piece about kindness in science, you know, titled, Science Should Be Kinder to Each Other. And obviously, you're not talking about letting papers go through the pouring in their logic or, you know, lowering the bar of peer review, but you're talking a bit about how science is undertaken. I mean, there is a history and science of somebody who's a workplace bully, if I can even use that term, that they run a lab, they control everything that goes on in lab. Sometimes someone's bad behaviour can be rewarded in science. What comments do you have on that? I mean, how do we, how do we, I mean, obviously, a lot of institutions are getting on top of that, but still, a lot of it goes on today. So what was the point of that article coming out and talking about kindness and science?

Naomi Oreskes: Yeah, well, this is a really big issue. And I wanted to write about it. And it's a tricky thing to write about, because it's a delicate topic. But what I wanted to address was exactly what you just said, that some people think that because we need to be intellectually tough in science. And if a paper’s no good, if the arguments don't make sense, if the data are insufficient, we need to be able to say that and say, yeah, this paper doesn't, shouldn't pass peer review. So we need to be intellectually tough, we need to be, you know, hard headed. But sometimes people confuse that with being hard hearted, or with being a bully, or being a jerk. And, you know, I think when I was, sort of, growing up in science, it was taken for granted that great scientists were often jerks, as if that was somehow okay. And worse than that, as if somehow that was a necessary condition for being a great scientist. Well, of course, he's a jerk, because he's a brilliant scientist. And so what I'm trying to do is to decouple those and say, no, it's possible to be hard headed without being hard hearted. And it's possible to be brilliant, and to be intellectually tough, but still treat people with respect and dignity and kindness. And it's not always easy. I mean, it's not to say that we don't become impatient and occasionally, you know, say, wow, this is a piece of crap. But, you know, I mean, I mean, we all have those moments, but like, when you write a peer review, I mean, I was… I gave this advice just the other day to junior scientists, you know, write down exactly what you think including, you know, this paper makes no sense. And then rewrite it nicely, right? But the point is, you can be intellectually tough and still treat people with dignity and respect. And that's what I think we need to be working for. And to separate out not, to conflate being a tough scientist with being a nasty person. And also not excuse it, because the other thing that happens, and I'm sure you've seen this in the United States here with Eric Lander, stepping down from the Office of Science and Technology Policy, that sometimes great scientists get away with bad behaviour, with bullying and harassment. People say, oh, well, he's so brilliant, he's a genius, that somehow that makes it okay. But it doesn't make it okay, because we're trying to build a community. And it's not enough for one person to be brilliant. We have to empower and support all the people who contribute to the scientific enterprise, because we don't get science out of individual geniuses, we get science out of all the different people who work on it and all the different perspectives that different people bring to bear. And so that's why it's so important that we don't excuse, you know, harassment just because the person was brilliant.

Matt England: And your comments just now make me think of one more question I had for you before we wrap up. I mean, you refer to working with junior scientists. Do you want to talk a little bit about what you're working on at the moment? What's your next big project? What are your grad students looking into?

Naomi Oreskes: Well, my grad students are doing a lot of different things. And one of things I'm proud of is that my grad students work on a lot of different things. And I try as much as possible to really encourage them to pursue the things that they think are important and not like to just have them be my minions. But the big new project is my new book with Eric Conway, which will come out next year. So one of the things that Eric and I showed in Merchants of Doubt was that a lot of climate change denial is motivated by a defence of the so called free market. That climate change deniers often fear that if we regulate the marketplace, this will be a slippery slope to socialism, communism, tyranny, etc, etc. And so we started becoming interested in, well, why did they think that? Because it's a kind of strange argument, it's a slippery slope argument that history does not support, like the evidence from history does not support that argument. And it's also sort of weird because the free market doesn't exist, it's never existed, there have never been markets that just exist unto themselves. Markets are human institutions, they're created by people, and they operate under sets of rules and regulations. I mean, there are rules for the marketplace that you can find in the Bible. So the idea that you could ever have markets without rules and regulations just doesn't make any sense. So we wanted to better understand why intelligent people would think this, or as my husband likes to say, why would intelligent people tell you to believe in magic, the magic of the marketplace? Like that's pretty weird when you think about it, right? Anyway, we discovered a kind of scary story. It's sort of, I think of it as a prequel to Merchants of Doubt, but a long history of propaganda in the United States to promote the idea of the magic of the marketplace, and also to promote anti government thinking that the government rather than viewing the government as an expression of the will of the people to view the government as the enemy, as a threat. And so that's the book. It's a big book we've been working on it for, I don't know, just about six years now. And it's just about done and it will come out early in 2023. So invite me back to Australia, and hopefully I can do another book tour.

Matt England: That'd be fantastic. Naomi Oreskes, it has been great talking with you. I really enjoyed the catch up. Thank you for joining us tonight, and also thank you everybody for joining us online.

Naomi Oreskes: Good night.

Ann Mossop: Thanks for listening. For more information, visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Naomi Oreskes

Naomi Oreskes is Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University. A world-renowned geologist, historian and public speaker, she is a leading voice on the role of science in society and the reality of anthropogenic climate change.

Oreskes is author or co-author of seven books, and over 150 articles, essays and opinion pieces, including Merchants of Doubt (2010), The Collapse of Western Civilization (2014), Discerning Experts (2019), Why Trust Science? (2019), and Science on a Mission: American Oceanography from the Cold War to Climate Change, (2021).

Merchants of Doubt, co-authored with Erik Conway, was the subject of a documentary film of the same name produced by Participant Media and distributed by SONY Pictures Classics, and has been translated into nine languages. A new edition of Merchants of Doubt, with an introduction by Al Gore, was published in 2020.

Matthew England

Matthew England is a Scientia Professor of Ocean & Climate Dynamics at the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre, and Deputy Director of the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science. His research explores large-scale ocean circulation and its influence on regional and global climate – from the tropics to Antarctica, and from time-scales of seasons to millennia.

England completed a PhD at the University of Sydney in 1992 and held a Fulbright Scholarship at Princeton University in 1990. He has previously worked at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France and at CSIRO’s Climate Change Research Program. He has been with UNSW Sydney since 1995, where he held an ARC Federation Fellowship from 2006-2010 and an ARC Laureate Fellowship between 2011-2016. He is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science and a Fellow of the American Geophysical Union.