Polly Toynbee: An Uneasy Inheritance

There's a kind of need to believe that people have got their just deserts, that we live in a society that has some kind of justice, and it's quite hard to accept that really isn't so. It's really against the odds for somebody to rise up.

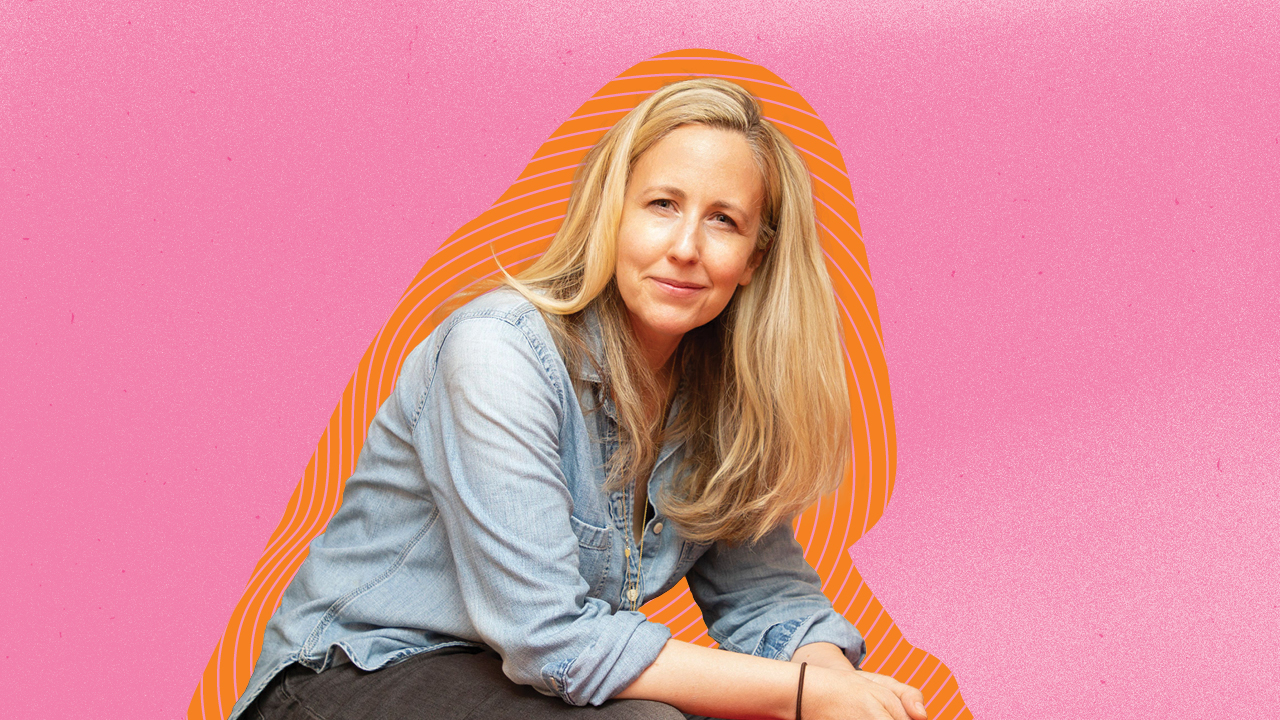

Is it possible to come from privilege whilst striving for a fierce socialist agenda? Polly Toynbee believes so. The prolific British Guardian journalist, commentator and broadcaster unpacks what it means to be privileged in Britain and Australia, and whether the deepening class divide can ever be transcended.

In an evening of conversation with journalist Nick Bryant, Polly opened up about her latest book, An Uneasy Inheritance, detailing how she still grapples with her charmed family history, and how she endeavours to dismantle the rigid class systems of Britain with her prolific writing.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and supported by Adelaide Writers’ Week.

Transcript

Nick Bryant: Good evening. What a lovely crowd. It's so fantastic to see such a full auditorium. Thanks very much for coming along. my name is Nick Bryant. I'm a former BBC correspondent, still in recovery after covering four years of the Trump presidency - the first instalment of the Trump presidency.

Audience reaction

Oh, let's, let's hope. Let's hope it's the only instalment.

Alas, I'm not David Marr. He was supposed to be here tonight, but David unfortunately is ill. He's suffering from Covid. I spoke to him this morning. He's still testing positive. He's regretting using the free tram service at the Adelaide Book Festival - the super spreader is on wheels - and he's gutted not to be here tonight. He was looking forward to it. And, we wish him well. We wish him a speedy recovery.

I want to begin by acknowledging, the traditional custodians of the land upon whose land we meet - the Bidjigal people. I would also like to pay my respects to elders, both past and present, and extend that respect as well to any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are in the audience tonight.

It is such a pleasure to introduce Polly Toynbee. When I joined the BBC 30 years ago, Polly was a giant not only of the BBC but of the British media landscape. She was the BBC's social affairs editor at the end of the Thatcher years, which certainly gave her an awful lot to talk about. Before that, she had established a great name for herself in the in the women's pages of the of the Guardian, the iconic women's pages of the Guardian.

After she left the BBC, she went to the Independent and then went back to the Guardian, where for the past 25 years, she really has established herself as one of the great thinkers on the left of British politics and one of the great public intellectuals of British life as well. She has written, a fantastic book. It's called An Uneasy Inheritance: My family and Other Radicals.

Getting to know Polly's family was fascinating. There are some amazing cameos as well. There's Bertrand Russell in there, there's Decca Mitford. There's even a naked Boris Johnson, which perhaps we'll get Polly to explain later. I mean, reading this book, I must say I thought there were about 5 or 6 screenplays in it, which seems appropriate on the night of the Oscars. It's an absolutely wonderful book. Please join me in welcoming Polly Toynbee to Sydney.

Applause

Polly, here we are, two Brits in Australia talking about our national obsession, which is class. We make assumptions about people the moment they open their mouths. We listen to their accents, the coded language that people use. Are your class antennae sort of out of action here in Australia?

Polly Toynbee: Not really, because I'm always very suspicious of countries that say, oh, we don't have class here, and I'm actually talking to lots of Australians. They all say, no, I'm afraid it's just another myth. But it's a very important foundational myth for Australia as it is for America. And of course, America is one of the most unequal places you can find.

So I think there is class everywhere but to different degrees. And what's really depressing in Britain is that it's going backwards, not forwards. And that's really what shocked me most.

Nick Bryant: That's something we'll get to speak about later. I'm fascinated by what made you write this book. You were doing a BBC documentary, as I understand it. The producer suggested to you that you actually sort of ruminate on your own background, but that was something you were slightly reticent to do.

Polly Toynbee: Absolutely horrified. I've never written about myself until this point. I've often written about class. I've written about society in all sorts of ways, but never about myself or my family - ultimately shied away from it. I was doing a program called The Class Ceiling, and in the course of that, interviewing a lot of experts who were sociologists, social scientists of one kind or another.

And I would ask each of them, well, tell me about your own class background. And suddenly they would reveal all sorts of things about themselves. And then the producer and I started more or less stopping people in the street. And anybody who asked has a story to tell. If you say to somebody, ‘Think of a time in your life when you've either been too posh or not posh enough.’ Everybody, when they stop and think, has a story to tell. That's either an embarrassment or a pain of some kind or another.

And it is a way of starting a conversation with people you don't know. That opens up so much about themselves, their lives, their family and the world that we all live in. So after I've been doing this for a while, getting very interested, wherever I was going, I was saying to people ‘Tell me.’ - this magic question ‘Too posh, not posh enough?’.

The producer said, ‘Look, I'm sorry, but you've really got to say something about yourself’. And I thought, well, they can hear my voice. They've probably got a pretty good guess as to what my origins might be. But no, I don't want to talk about myself. Much too embarrassing. You've got to say, he said, describe your family, your background, where you come from.

So in a kind of very, very - as short as I could make it - I said, ‘Well, I come from a long family of professors, teachers, writers, campaigners, politicians, and they have passed this on from generation to generation. They are the sort of people, as a social class, you might think in the Middle Ages, would be the ones wearing black and carrying the quill pen and running the administration and, the bookkeeping and all of that. Always, always professionals, well-paid, successful, landing on their feet, well-educated, educating their children for generation after generation.’ And I stopped it there.

But after I'd done this program, I felt I had to go and think about this, to think about being thoroughly, totally middle class or upper middle class, thoroughly privileged forever - as many of my family as I knew about - was something to contemplate and something to discuss and something to come to terms with in a way, particularly as all of my family have been on the left. They've all been radicals and campaigners, all the way back to passionately anti empire, passionately pro-Irish home rule everything, cause they were always on the left side and all of them lived with considerable embarrassment about the hypocrisy of how do you manage to be a well-off professional person and yet be on the left.

And there are lots of wonderful biographies, autobiographies, memoirs people have written about how they've made it up from being working class and stories about rags to riches – or not necessarily riches.

And the wonderful book I've been reading recently, you've probably read – Lemn Sissay, the great poet. His memoir about coming from a childhood in care, really brutalised childhood and making it up to being a great poet. Now, those are great stories. But I thought, well, nobody's actually written about being middle class forever, about staying exactly where you were born and what privilege means. Right?

Not underprivileged, but about privilege. So I felt I had to face up to it and do that thing and be honest. I mean, of course, in the course that I went searching for any working class relationship I've got of any sort at all. Not a twig, not a branch, not a root. Nothing. Nothing. I had one Australian great great grandmother who had been a governess, but it turned out she'd come from an extremely well off family, had just fallen down a bit in the world, and then married very well in Australia.

Nick Bryant: One of the interesting things you say in the book is how British people invent a working class background. Sometimes there's a kind of a delight in finding that. I'm delighted that you have introduced us to your family because they're an extraordinary bunch. I mean, some of them are a world famous. I mean, tell us about Toynbee Hall, for instance. Not to be confused with Tammany Hall in New York, Toynbee Hole in the East End of London. Tell us about Arnold Toynbee. Tell us about some of the women as well, because, you know, we tend to think it's this is a kind of male story, but there's some extraordinary women in your background as well.

Polly Toynbee: The Toynbee Hall is a wonderful community centre in the East End of London. It's a very peculiar place. It's a little model pastiche Oxford College, dumped down in what was then the very poorest bit of the East End - no longer. And my grandfather, Arnold Toynbee, the historian, his uncle was called Arnold when I was a young social worker and academic in the East End, working together with his friends Henrietta and Samuel Barnett, who were great progenitors of all kinds of good social movements.

And he died very young, they said, of diseases caught in the East End, but I've no idea if that's true. And so they founded Toynbee Hall and called it after him. And since then lots of members of my family and various people have been there and worked there. That it's where, actually lived and worked, and said where he learned his socialism in the East and William Beveridge, Lenin spoke there.

It's had a whole throughput of people, on the left side of politics who go and work there and learn, because they were mostly middle class people learning about working class life by working in that community centre.

Nick Bryant: And William Beveridge, the famous architect of the welfare state, really, and the brains behind the National Health System. These Arnold Toynbees are fascinating - one of them is a historian who I think maybe not coined the phrase ‘industrial revolution’, but popularised it. And then there's another historian, Arnold Toynbee, legend in the historical field in Britain, who appeared on the front cover of Time magazine. I mean, you know…

Polly Toynbee: Yeah. Well, the year I was born he was on the front cover of Time magazine. He was -became an enormously popular historian. He wrote 12 volumes of A Study of History, where he was trying to account for the rise and fall of civilizations. Why? What made civilization burst out in some places, not in others? What made it rise and fall?

He concluded that it always fell through its own corruptions and its own errors and mistakes, and that there was no necessity for civilizations to fall except for their own corruptions. So he became immensely popular and, a sort of Fukuyama of his day, in a way.

Nick Bryant: And he had two really amazing sisters as well that often got sort of airbrushed out - I don't know whether you've read Anna Funder’s Wifedom, but there's a there's a kind of element over that in this story.

Polly Toynbee: He was brought up, he was brought up - very educated mother who'd been at Cambridge University, but of course, hadn't been able to collect a degree because in those days women couldn't. But she got a First without being able to claim it. And, and his father went mad very young. So his mother was left alone with three children to bring up, and they perched with a rather grumpy relative who was an old sea captain.

And they all had to get scholarships to get into good schools and good universities. And so there was Arnold, who became a professor then his sister Jocelyn became, professor of archaeology at Cambridge. And their younger sister, they slightly despised Margaret because she was only a don at Oxford. She never got professorship. But so all the way through, there have been these sort of tremendous academic overachievers.

Nick Bryant: And there's in Australia in the mix as well.

Polly Toynbee: Indeed.

Nick Bryant: Tell us about Gilbert Murray, whose father was actually the speaker of the New South Wales parliament I think, a campaigner who tried to abolish the death penalty here and tried to abolish enforced transportation.

Polly Toynbee: Yes, yes. Absolutely.

Nick Bryant: Tell us about his son, Gilbert.

Polly Toynbee: I mean, I think - he was an Australian. His father was called Sir Terence Murray. Sir Terence Murray's father had been sent to Australia as paymaster general as a reward for fighting in the Battle of Waterloo and was given a chunk of land, in Canberra near Lake George and his son – it was amazing - reading David Marr’s book I understand it a bit more - was sent off at the age of 20 to be a magistrate and in charge of a large district.

But they were all very… they were they were radicals by nature because they were Irish Catholics. That's where the sort of inspiration for, that instinct to be on the left, to be for the underdog, came from. But they were all highly educated and really cared about education.

And when he came to Australia brought huge numbers of books with him. And he did very well - Sir Terence Murray did very well - and had cattle and land, and then he took to the drink and, there were droughts and floods. He lost everything he had. And in the end had nothing at all and died quite young. And, really died of drink.

His son was Gilbert Murray, the one who was married to the governess, Agnes. After Terence Murray died, she took Gilbert back to London where they lived in relative poverty, but again, very sort of educated, genteel poverty. And he had to win every scholarship all the way through. And he got scholarships to Haberdashers House, scholarship to Balliol, and became the Regis Professor of Greek at Oxford.

And he was also a tremendous campaigner for every sort of cause, as his father had been, and certainly in Australia, he was he was a vegetarian, teetotaller, passionately anti-colonialism of all of all sorts. Tremendous Irish home ruler, anti capital punishment for women's votes, all of those things which his father had been to. His father had actually spent a lot of time collecting Aboriginal languages for fear that they would die out, and had been the, you know, very pro indigenous rights.

So that was their background and why they were all kind of the same state of mind of being on the left. But then drink was also part of the story. They were all drunk, temperance, drunk, temperance, all the way down too - which was another part of the family's story.

Nick Bryant: And here's where one of the screenplays come into play. Because Gilbert Murray married into the aristocracy, didn't he? And it wasn't any kind of aristocracy. It was the aristocracy, the Carlisle family that owns Castle Howard, which you'll have probably seen on shows like Brideshead Revisited and Bridgerton. I mean, it's this extraordinary journey from Australia into the kind of upper reaches the upper echelons of the British aristocracy.

Polly Toynbee: Yeah, absolutely, because he wasn't that grand, but he was very clever, and he was with a radical set of young people on a picnic in, in Oxford. And this incredibly grand woman came up to him, the Countess of Carlisle, and said, ‘Young man, I believe you are a teetotaller’. He said, ‘Yes’, ‘I believe you are a vegetarian’, ‘Yes’, ‘I believe you are a radical’. He said, ‘Yes’. ‘Right. Then you will come and stay with me in Castle Howard’. She was off the left herself, despite being immensely grand. She was again a great, Irish home ruler, which is a thing that's split the Liberal Party at the time - and took him in a group of his friends up to Castle Howard where he fell in love with her daughter and married her - Lady Mary Howard.

And so that was the sort of various aristocratic gifts of the family. But they lived again, a life of… they gave away half of their money. They gave away half of his income and fought lots of radical causes. And when that was a general strike, they, you know, they were supporting the strikers and they were very much always on the left.

Nick Bryant: Tell us how your family was regarded - obviously now it's regarded as well, it's almost like the Kennedy family of the British left, in a way. But I wonder how they were regarded at the time by some pretty reactionary conservative forces. I think Arnold Toynbee, the historian, immediately comes under fire from some of the really sort of right wing historians at Oxford and Cambridge and all that kind of stuff. I mean, it was a it was a family that was in the fight for generations.

Polly Toynbee: It's important to remember that, that their causes were all hopeless, lost, useless causes. They were eccentrics and mavericks and regarded as, you know, generally weird for having these views. And so always remind myself and say to anybody else, they won and won and won again. In their own lifetime - I mean, Gilbert Murray stood -there was an Oxford seat and he stood for the Oxford seat.

Endless campaigns within the Oxford Union, on capital punishment, on every good radical cause. And he lost, lost, lost again every time. They all lost the Oxford seat their causes in their lifetime. But in the end, I would say to them now if they were here, ‘Look, in the end, you were on the right side and you won. And in the end, it is always worth battling, even if at the time you feel it's a lost cause, it's not’. Except for the big one.

Nick Bryant: The big one.

Polly Toynbee: The big one. What would shock them most is that the one thing that has gone backwards, is social class. Is inequality. And they cared passionately about that, too. So that, in a way, the most important thing - we had a story from 1900 going all the way to the late 70s, of becoming more equal in wealth and in income, and in working rights and in trade unions and everywhere you could, might measure gradually becoming more and more equal.

Then Thatcher came in and the graph took off in the opposite direction. The middle to bottom wages were held down. The outsourcing of nearly all public manual jobs meant that pay in the public sector fell, and people at the top, the lid came off and started earning astronomical sums. And it has stayed that way pretty much ever since.

Came down a bit in labour time, back to where it was. And the idea that birth, that social mobility is worse, I think that would really shock them. Birth is destiny more certainly in Britain now than the year I was born. And we've always had the story, I suppose because the social history we're taught was a social history of progress, you know, trade union rights, everything getting better, people getting more rights of every kind, voting rights. And you sort of expected it to go on like that. It's how I was taught O-level history. And to suddenly find that it's stopped and it's not true any longer, I am still profoundly shocked by.

Nick Bryant: Yeah, we were talking before coming on stage. I mean, one of the reasons I haven't lived in Britain for the last 25 years is because of class and I always didn't like the idea that so many of the friends that I grew up with at my comprehensive school in Bristol were reconciled to their fate from a very early age, and the class system was very oppressive.

And I went to America because I, you know, I had the American dream as a bit of a myth, but there is this sense of possibility there and it gives America an energy. But there's a paradox. When I left Britain, you thought that things were changing. Margaret Thatcher was the daughter of a grocer. She didn't come from the aristocracy.

She went to Oxford, but she didn't come from the aristocracy. John Major, who took over from her, spoke about a classless society. He hadn't even gone to university. Tony Blair, he spent a lot of time in Australia, weirdly. His father was an academic in Adelaide. And some people regard Tony Blair as Britain's first Australian prime minister because he was famously classless and, really wanted to bring in that classless society. You had three prime ministers in a row who spoke a game of sort of getting beyond class and transcending class. And yet, you know, two of the most recent prime ministers of both being Old Etonians, you know, well, what went wrong?

Polly Toynbee: Well we've had five Old Etonians since the war, which is extraordinary.

Nick Bryant: And 20 in British history.

Polly Toynbee: Yes. Amazing - what went wrong? I mean, a lot of that is veneer. I mean, I, you know, growing up in the 1960s, Beatles, all of that, everybody said, ‘Look at young people now. They're all classless, aren't they?’ And a lot of it was veneer. It's about looking more alike, wearing more the same clothes. But the really important things - about opportunity, about to what extent your parents set the course of your life, to what extent you're going to not get the education you should get because your parents haven't had that education, to what extent you're always going to earn less because you haven't had that education. And, that's what's so dispiriting that it is now the case that what you inherit matters more than it did when I was born. And so I think people are often deluded. We like to pretend we live in a meritocracy.

It feels better. And what's sad is that often people at the bottom end also believe they live in a meritocracy and will say, ‘Well, if only I'd worked harder at school. You know, I could have made it. And I just didn't try’. And they think they failed. Not ever that the system or the school failed them. There's a kind of need to believe people have got their just deserts, that we live in a society that has some kind of justice, and it's quite hard to accept that it really isn't so. That, you know, it's really against the odds for somebody to rise up. But of course, many people do, and many more people are going to university than did. Nevertheless, the injustices is very deep and worse than it was.

Nick Bryant: You brought up the inheritance from our parents and I'd love to talk about your parents. I'd love to talk, in particular, about your mum; a debutante, somebody who was presented to the King, married somebody who I think I'm right in saying, her father thought would be killed in the war. So it didn't matter that his social status was different from hers. Tell us about your mum, because she's an extraordinary character.

Polly Toynbee: My mum was great. She was wonderful. And she came from - her mother had some money from a the brewing family and they were sort of lower debutantes because even within each niche, there are the top debutantes and the bottom debutantes. And she always wasn't a very grand one. Nevertheless she was. And, she met my father, who gate crashed the deb ball.

My father was, he was perfectly posh, he’d been at Oxford and, but he was very unsuitable and disreputable and rather drunk. And her father, who was a colonel in the army… they rather liked him, but they did think he'd be killed because they married in 1939 and she was very young and they thought, well, it's going to be like the First World War and just as many people will be killed. But my father was very much on the left. My mother was on the left. Her mother was on the left. Despite this, rather grand… they were sort of liberal people and, my father was a communist. He was a communist, all the way through his time at Oxford. And before that, right up until the Hitler Stalin pact, when a whole lot of people had been in the Communist Party at that point, walked away.

But he stayed on being a radical all his life. He had deep feelings that the world was going to come to an end. He always thought world was about come to an end. He was a a millenarian in every kind of sense. So he was a founder of CND and felt passionately about that and brought us all to feel that we were very unlikely to make it into adulthood, particularly as we were his child actually, he was our father. So much so to the extent that when we went on holiday to Wales, driving off in the car to Abersoch, we had to turn around and come back again because my father had forgotten the large jar of suicide pills to kill us all when the bomb dropped, because he we'd all read Nevil Shute On the Beach, and we all knew about Strontium-90 and radiation sickness and what it was going to do with us. On the other hand, we used to look with some alarm at this large jar of pills. I think they were only kind of aspirins or something, but…

Nick Bryant: I read the use of the holiday in Abersoch and I thought because my family used to holiday in Abersoch year after year after year, it's this tiny bit on the on a peninsula in northern Wales, remote spot. And somebody told us afterwards or told me afterwards that it was the only place in Britain that wouldn't get hit by nuclear fallout in the event of a nuclear war. So perhaps that's why you finally went?

Polly Toynbee: Maybe that’s why! Right. In the next edition of the book that's coming into it? I never knew that.

Nick Bryant: Yeah. No, surely I might say Abersoch is not the Welsh Riviera. But it makes perfect sense of why my parents took us there. You speak of how your mum tried to escape her class. She did things like driving school busses…

Polly Toynbee: Yeah.

Nick Bryant: ...doing a lot of charity work.

Polly Toynbee: Yes, she did. Because she was so grand she never felt very educated. She hadn't been to university, and she didn't have any qualifications, but she did - she spent many years driving, driving school bus and running a whole scheme for the holiday scheme for kids and that kind of thing. Yeah.

Nick Bryant: And that's something that you did as well, isn't it? At the beginning of your journalistic career, you did it, and the end of your journalistic career you did it. Perhaps we’ll talk about that a little bit later, but you had a fascinating schooling. You went to a posh school in Bristol, which is my hometown.

You went to a comprehensive school in London, a fairly fashionable comprehensive school. You went to Oxford, you decided to drop out. Like your mother you seemed to be trying to escape your class.

Polly Toynbee: I think I was in a way - there were a lot of things I really hated about Oxford. I think, yes… and I left Oxford and I went and worked in a factory for a while. I'd written a novel already, which came out when I was at Oxford, and I thought, ‘I will live a life working with my hands during the day and writing wonderful novels at night’.

I quickly discovered why it is that people work in factories or laundries or, places that don't often write novels. You come home in the evening completely deadened and exhausted. And after that I went off for a while to… well I went to work for The Observer newspaper, which was a great newspaper, and was put on the news desk.

And I suddenly realised I actually knew nothing about the country that I lived in. You know, a middle class girl went to Oxford, lived in South Kensington. And so I took time off and went and took a number of jobs around the country. I worked in a car parts factory, Lucas's Car Parts factory in Birmingham. I worked in Port Sunlight for Unilever.

I worked in a hospital in London as a ward orderly. I joined the Women's Army for a bit. I did a number of jobs- just to get a feeling of what - not looking for poverty, but what ordinary manual work was life like. Meeting people, talking to people. And then I wrote a book about it, and I think I was a better reporter as a result of that, knowing about different parts of the country and about different sorts of people.

I never for a moment could imagine that I knew what it was like to be one of those people, but at least I knew what the work was like. At least at a time of many strikes in the 1970s, which I was reporting on, I understood why if somebody went on strike, they were being cheated of a five minute tea break, which the right wing press would make fun of - I understood how every minute of that five minute tea break was really crucial if you were standing on your feet on an assembly line all day. But then I went back and did it again from a position of much greater knowledge, over 30 years later, when I'd been BBC, BBC social affairs editor, I'd written about social policy and social research for many years.

I went back and wrote a rather better book and did that again. Took jobs... I took a flat in a council estate not far from where I lived at the posh end of Clapham, and this was in a very rundown council estate where I was able to rent a flat for a short time, and took whatever jobs I could get in the local Jobcentre.

And I took a job in a call centre in a cake factory, in a nursery, in a an old people's home as a carer, a care assistant. And by good luck, back in the same hospital where I'd worked over 30 years before, in the same grade of job, this time as a porter. Last time I'd been a ward orderly - and after I'd done it, I took my payslip from both occasions to the Institute for Fiscal Studies and said, tell me what's happened to my pay?

I've been the same grade of job in the same hospital. What's happened to my pay in that time? And they said it's fallen by about a third in real terms. And that described… although I'd written about it and broadcast about it in a rather abstract way,… about what had happened to inequality, that explained how it had happened. All the jobs in the hospital and in every other public sphere after Thatcher had been outsourced. It was to a company called Carillion, which fell apart, and then usually to agencies and often an agency working for another agency. I never managed to get myself in all those jobs, a job actually working for the state. They'd been outsourced in order to be able to pay people less, no longer unionised. And this is what's happened throughout the workforce. And that is how people are paid so much less than they were.

Nick Bryant: I found this a very moving part of the book as you’ve sort of described so evocatively the difficulties of trying to make ends meet on such a small amount of money in such difficult circumstances. And what struck me too, was your fear of being recognised. Polly is very well known in Britain, obviously. You were working in a hospital where you knew some of the consultants.

You had this job with the Foreign Office where you were working in the childcare - so you're walking down Whitehall and you're seeing these sort of labour grandees and these British politicians walking towards you. You think, ‘Oh, they're going to recognise me’. But you said you were invisible. And the fact that you've become a member of this kind of underclass temporarily makes you invisible to them.

Polly Toynbee: I mean, that was a good reason for doing it myself. It reminds you that you walk through a kind of Green Baize Door into another world. You're wearing the uniform, you're wearing the polo shirt with the emblem of your company. You're wearing cleaner’s tabard, and you become something else. So that in the hospital, for instance, I mean, a number of those consultants had interviewed often when I'd been at the BBC, and I knew them quite well.

But if I was pushing a bed or a trolley or a, somebody in a wheelchair, the consultants would pass you by just not notice you. You were this person in the hospital uniform and that was it. You were your class, your category. And certainly walking along Whitehall where, you know, it was Labour times. And I used to be in and out of those departments all the time.

Terrifying when down the road came Peter Mandelson, Philip Gould and a number of other people I knew very well. Peter gave me - and I was wearing a kind of.. it said Kinder Quest - tabard. I had a double buggy and two toddlers on straps, and we were walking down Whitehall and into Horse Guards to take the kids out into Saint James's Park to play.

So Peter Mandelson looked at me for a moment. Just for a moment he thought he might know me. And looked away. ‘I couldn't possibly know somebody like that. How could I?’ And it was a great relief to me, because I wouldn't have known what to say to my co-workers either. It was altogether desperately embarrassing because I couldn't, in the course of doing this, sadly, tell the co-workers what I was doing because it would put them in an impossible position where they would have felt they ought to tell their manager that I was, as it were, a spy. So I couldn't put them in that position so I could never tell anybody I worked with, actually that I was a journalist.

Nick Bryant: Peter Mandelson, of course, this great Labour grandee who represented a seat in Hartlepool, a working-class constituency. A famous story, an urban myth maybe, but he went into a chip shop, he said, ‘I'll have the guacamole with the fish and chips, please’. He was looking at the mushy peas. Which speaks of a class in Britain.

Polly, I wonder whether class has been superseded by other ways of identifying ourselves, by race, by religion, by gender, by sexuality? In the hierarchy of sort of self-definition, does class still occupy the pole position in Britain?

Polly Toynbee: That’s another reason I wanted to write this book in a way. Identities, different identities are at risk of taking over from the bigger question of class, because the disadvantages often multiple disadvantages as an intersectionality of being both, you know, a single mother, a woman, and maybe, with not a very good education, let alone if you're black as well, multiple deprivations.

And I think there's been too much emphasis, in a way, on the separateness of each kind of disadvantage you can have, when overarching it all is the big one. And it brings all those things together. And I think in politics, a danger perhaps of people becoming so interested in the particular, victimhoods or… of different kinds that they forget that the class struggle still really matters. It is really important. And, it covers all of those things.

Nick Bryant: Because you have this paradox at the moment, both in Britain and America. I mean, you've got a New York billionaire tycoon who is a hero of the Rust Belt, a working-class hero of the Rust Belt. And in Britain, you've got this Old Etonian populist, Boris Johnson - we should explain the nudity story at some stage - you saw him as a baby when it was when he was an adult - you have this paradox with some of Boris Johnson's strongest support comes from the working class. How do you explain that?

Polly Toynbee: It was Brexit really. It was a kind of - there was a kind of genius in the Brexit campaign. It was, ‘take back control’ for large numbers of people who felt they really had lost control of their lives. Their pay had been held down for a long time. Life had got harder. Their children were less likely to own a home.

Their public services were worse. They felt a deep sense of grievance. And so the brilliance of the Brexit campaign was to make them feel that this was all somehow due to Europe, either Europe or the elitists who supported Europe. And also, Boris Johnson is a charismatic character. He's very good at engaging people. He will say anything to anybody, even if they're completely contradictory.

So he had this line as well, which was very successful, of saying, ‘I'm going to level up the country’. You know, ‘The North will be levelled with the South’, and talked a sort of language of social democracy, which was bizarre. And of course, once in power, he had absolutely no policies whatever that began to touch any of the things that could really make a difference, either regionally or in any other way to that, to the many great inequalities.

But it was a clever combination and he made people laugh. Not many politicians make people laugh. He had - has, he may be back- authenticity in the sense that he's kind of authentically himself in a way that Trump is, too. I mean, Trump isn't pretending to be anything different to what he is. And I think people like that about it.

They feel all these other politicians being so careful, so cautious to say the right thing, not to say the wrong thing. And these kind of ‘devil may care’ people have what seems to them to be sincerity. Of course not. But I think that's the sort of magic that they tap into.

Nick Bryant: You talk about how social mobility has actually got worse and yet the policies of the left, and this is true globally, I think, have become more timid in talking about social mobility and certainly more timid in proposing policies to address it. It's like they have made major - in America Clinton made major ideological concessions to Reaganism, Blair made major concessions to Thatcher, in Australia labour politicians are still traumatised by the 11 years of John Howard - how does how does the left get out of that kind of trap?

Polly Toynbee: I think there's always the fear that Britain is an essentially conservative country. We may be just about to find that that's no longer the case. Failure of Brexit may have broken something in a way that I think we may be about to see something that is not just the normal pendulum of politics, but a really fundamental change in that rejection of the Tories this time.

But we shall see. But I think you mustn't underestimate how much labour, how much Tony Blair did. He was very careful how he seemed and how he talked. But, you know, he said he would abolish child poverty within 20 years. Well, by the time he and Gordon Brown left they had almost got halfway there, which is pretty impressive after the depth of poverty that they inherited in 1997 - a million fewer pensioners in poverty, a whole tax credit system brought in, 3500 wonderful Sure Start Centres, which are kind of family hubs for families everywhere for early years teaching, realising that, you know, every pound you spend on early education, early years, will yield far more in a child's development than - everything later kind of becomes remedial. And that was brilliant. It really just got underway and that moment the Tories came in, they swept it all away.

There are very few of those left, so I wouldn't underestimate what Labour achieved and I'm very optimistic about what Labour will achieve next time. Even though they will be ultra cautious all the way through the election, promise very little and keep saying what they won't do more than what they will do. I'm optimistic that, it's going to be on the up.

Nick Bryant: I love the optimism of your book. I want to open up to questions from the floor very soon. If we can get the microphones ready and I'll go onto Slido. I thought Slido must be a Australian invention because of the ‘o’ on the end of it, but apparently that's not necessarily the case. Before I go to the audience, I want you to talk about The Uneasy Inheritance, your book title. Why is it and why is it uneasy? You speak of an oppressive virtue. So tell us what you mean by that.

Polly Toynbee: It's quite oppressive virtue that some of the... my relatives were very virtuous and very good, and they were quite hard on their children. They weren't very good parents. But the uneasiness is really about myself and about other people on the left who are middle class and don't quite know how to cope with that. I mean, you mentioned a bit of research - just as my book was coming out, I managed to get it there, there was some research that the London School of Economics did, and they asked a whole lot of people who were senior management or professionals, to describe their own class background. And something like 47% of them said they were working class. So the researchers said, well, how can you be working class?

And they would say, well, my parents were. Well, okay, yes. But quite a lot of them would say, actually my grandparents were. And one of them even said ‘My great grandfather was a miner’. Because of the need to believe that you have, the place, the privilege that you have - and I think we all live with that - all of us who are middle class, we want to believe that we're here through our own merit.

Well, someone like me will never know. I have no idea. If I've been working class I might have stayed as firmly where I was as I have in the life that I live. And I think that uneasiness is there with a lot of people, particularly if they have any social conscious, if they're at all on the left or the liberal side of things.

I mean, the English liberal side of things, not the Australian. They have a wish to believe in merit, in their own merit, but an uncomfortable sense, an uneasy sense, that they don't deserve the privileges that they have. And I think we don't, you know, I think we've probably… I would vote for some much more egalitarian party.

I don't think we do deserve to live lives that are so much better than other people's lives. So that's the uneasiness. And how do you cope with that? How do you cope with not being Mahatma Gandhi and giving away everything you've got? Because the Right are always on at you. They're saying, you know, ‘Champagne Socialist- hypocrite’.

But of course, if you are working class they say ‘politics of envy’. So they get it one way or the other.

Nick Bryant: I mean we now have intergenerational trauma. It's almost as if there's an intergenerational angst.

Polly Toynbee: Yes I think so. I think they all felt the sense of privilege - they were all brought up to feel. ‘Be aware of your privilege, be good to other people’, you know, ‘despise all of those other middle class people who are constantly contemptuous or making fun of working class people’, putting on funny accents, the terrible things that the well-off Right do and say about the working class ‘scroungers, skivers’, all the rest of it.

Nick Bryant: Jane please, question.

Audience 1: Well, it's an obvious one really. Because Australia has the second most segregated education system in the OECD on class lines. But we don't talk about it because Australia, alone in the Western world,, gives huge amounts of public money to private schools with no reciprocal obligations except to obey the law. And even then, as Four Corners last Monday, that revealed that's loosely, kind of obeyed.

And this is regarded as part of egalitarianism because it's about parental choice and aspiration. But now 41% of government schools in Australia are designated as disadvantaged. 3% of Catholic schools who say they’re sort of public really, although they charge fees and decide who they'll take and who they won't take and where they'll service, which communities they'll service.

And 1% of independent schools are called disadvantaged and yet it is the unspeakable issue in Australia. I'm a mad feminist. No one minds that. It's my defence of public schools that makes me unacceptable socially, as. And there are a lot of people in this audience who have sent their children to private schools will feel uncomfortable about what I'm saying right now.

But I would like your comment on this because it is Australia's shame. We are as blind to the effects of this segregation in our education system, and the outrageous funding of public schools. The school on Four Corners gets $6.5 million a year in public funding, while charging 53…

Polly Toynbee: I’m amazed! I never knew this.

Audience 1: No, no one in the world knows this. It's a great secret. And it is despicable, shocking. And it is bad for Australia's future as the lack of gun control in America is in America, and we are as blind to his effects as the Americans are, in my view. I'd love your comments on that.

Polly Toynbee: Well, thank you very much for telling me about that, because I didn't know it. I should have known it. I've never been to Australia before, I'm afraid. And I will certainly follow this up and find out more because it's very interesting. In Britain, as you know, we have our private schools which are called public schools, which between 6 and 7% of children go to. We have some grammar schools left, which is another very socially divided.. you don’t pay to go to them but socially divisive in the sense that children get huge amounts of tutoring to get past the 11 plus exam to get into it. There is a huge difference between schools in good areas and bad areas and people moving to more expensive houses next to good schools, which is a way of paying for education.

I'm very glad that the Labour Party, one of its radical pledges is to, is to charge 20 to 20% VAT on all private schools, because at the moment they get 20%, you know, sort of tax free. So, that money is going to be used for state schools. So that's a gesture in the right direction. I don't think they will get close to, you know, the idea of banning in private schools. They might get close to taking away their charitable status, but 20% onto the fees is a good gesture. But no, our education system is divided in ways that are very much to do with where you live. And, you know, you live in a poor area, you go to a poor school where it's harder to get teachers to teach. That's the fundamental part of inequality right from the start, I think.

Nick Bryant: I've got a question here, Polly. And, bearing in mind you have stood for Parliament, haven't you? Member of the social and... SDP, back in the 80s. If you were the prime minister what would be the first three things you would do to tackle and reduce, disparity?

Polly Toynbee: I would bring back Sure Start. I would absolutely. Every single area would have within pram pushing distance a wonderful Sure Start that will help families right from the start. Any child that's in any danger of falling back at all on language and reading… all of those things right from the beginning. Any problems the family have - because the best of the Sure Starts had everything - they had, you know, mental health help for adults as well as for as well as if the children had any problems.

And that's the big one I think I'd begin with. I'm in, of course, are, you know, hugely reform the benefit system to make sure that, at least put back the appalling cuts that have happened in the last 14 years under this government, that just rendered people in work – most of the people on benefits are in work, we have very high employment, but they're in rotten jobs that are very insecure and pay very little.

So I would start by reforming the benefit system and make sure that nobody falls below a tolerable a standard of living. And then I think I would probably again go for education next and go for further education colleges, which are wonderful places of great - for second and third chances for those children hasn't made it through to A-levels and, have really good skills and catch up for them because everybody always thinks about universities and A-levels and at least half of the children go to these FE colleges that have been absolutely decimated by this government.

Nick Bryant: Talking future prime ministers, there's a question here: What is the point of Keir Starmer? I'd ask a follow up to that: Is he going to win? Is this a slam dunk for the Labour Party? They've been out of power for a long, long time.

Polly Toynbee: The point of Keir Starmer is he's going to win.

Nick Bryant: But does that not that speak of the problem. I mean one of the reasons why Keir Starmer will win, presumably, is he's very risk averse. He's not really proposing that anything that's particularly radical, he's a kind of quite a conservative Labour Party leader in the kind of mould of a Blair.

Polly Toynbee: Well, wait and see. I mean, he's there's some things that are more radical than Tony Blair did before he came in. He talks about class. Tony Blair would never talk about class. He talks about equality. Tony Blair would ever only talk about equality of opportunity, which is what the Right talk about as well. So I'm very optimistic that he and Rachel Reeves, who I think is great as well.

Nick Bryant: She's the Shadow Chancellor.

Polly Toynbee: Yes. She's the Shadow Chancellor… will be far more radical than we think. On the other hand, they are inheriting such a terrible situation. They're inheriting an immediate 20 billion black hole in spending. And that what the current Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has just done is to say ‘I'm giving away tax cuts now. I will take it back through spending cuts after the election’, because he won't be there and he won't even say what these spending cuts would be.

It leaves Labour with that to fill before they even start to do anything better. It's a very hard inheritance that they've got. But I'm optimistic that they will do the best they possibly can. And I haven't felt optimistic for a very long time. And I think you also have to remember that Labour suffered its worst failure since 1935 under Jeremy Corbyn.

You know, Corbyn was a catastrophe. He was unelectable, impossible. And Labour had to pull itself back. Nobody thought they could do it within five years. We thought it take ten years to pull back from that, to get to such a winning position in such a short time has been completely remarkable is true. It has been so helped by the conservatives and everything that they've done and everything that they've been and thank you Liz Truss.

Nick Bryant: Sir, please.

Audience 2: Thank you Polly. Long time reader, first time questioner. Late in my life I've come to a second career as a columnist of sorts. Only two so far in the Guardian. But one of the things in my previous life, I was looking at, things to do with, spatial conditions, and I've come to realise that the Left / Right continuum is not suiting us very well.

I'd like your comments about an idea that maybe it's a three dimensional thing now, like the triple bottom line, there's a social thing of Left and Right, but there's also an economic thing that runs through it at right angles to that. And then there's probably something that's environmental that runs from top to bottom, and that there's no such thing as people of the Left anymore. There’s is kind of diaspora of people in different ways, seeing the Left, and it seems to me that the only way we're going to move forward is to understand that it's much more complex than a simple Left / Right. That’s all.

Polly Toynbee: I think you're right in the sense that, I think the environment and the importance environment does change the dynamic enormously. And in some ways cuts through some party lines in that there are quite a lot - and one of the reasons that, you know, the conservatives will do so badly, is that there really are quite a lot of people in traditional conservative seats who are very worried about the environment, and they really care about the terrible things about, you know, the privatisation of our water industry through pouring sewage into the sea and into rivers, because of course, they've underinvested, and the indignation felt by these traditional Tory voters who might in their time have been kind of Thatcher supported or thought privatisation was a good thing. I suddenly pulled back and realised that that's not true. And also about energy companies and the need for investing in sustainable energy and all of that. So that is beginning to break the traditional Right / Left, if you like. And Left consists of a whole lot of different constituencies of people with different passionate feelings about things.

But nevertheless, when it comes to the hard economic questions: Who gets paid what? Who owns what? How much wealth has excess aerated into the hands of the top few percent? You know, during Covid that happened again, soared upwards. I think there is still a gut sense of social injustice about inequality itself. And that is a Left/ Right spectrum, if you like.

Nick Bryant: I think we've got time for one final question, sir.

Audience 3: I just want to question your optimism a little bit, because your account of Blair's many splendid achievements just brought into relief for me the ease with which all of that unravelled as soon as the global financial crisis hit and left… we found a government and a party and a tradition in a way which had no meaningful response to that.

No way of accounting for what happened. So this great fraud was perpetrated, that it was excessive government spending that had created the crisis. Hello. But the problem was that, as I see it, and this is why I ask about the future, the Labour Party, it seemed to me, had spent a lot of time in government enabling and lauding the activities of the city, of the financial sector and was therefore rhetorically, intellectually and politically defenceless when the blow came from that direction. Is there any evidence that the Labour Party has learned anything from that experience?

Polly Toynbee: Well, you're right about the unravelling and how quickly it happened that that very first budget in 2010 of George Osborne's and David Cameron's just got away so much, so easily with so little protest. And whether it was cutting benefits or whether it was cutting whole social programs, and cutting right into the NHS, which is on its knees. I think that this Labour shadow cabinet is thinking very hard about how do you nail things down, how do you make things so that they can't just be pulled all the way back?

I mean, in the end, you could only do that by nailing them into people's hearts, by making people feel that to touch a Sure Start program is unthinkable. I mean, they do think that touching the NHS is unthinkable and one of the reasons the government is doing so badly is that people are so shocked to have seen the NHS demolished in the way it's been, but not in any… They didn't dare touch its principles, they just underfunded it. And I think Labour is thinking hard about that. But in the end there is no difference except persuading the people that they want something better. And it is for this late future Labour government to persuade people that, there is a better way of doing things, showing that you can do it better, and making sure that it's never reversed again.

Nick Bryant: And the and the clock in front of me has just ticked down to zero. Please will you join me in thanking Polly Toynbee.

Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. For more information, visit unswcentreforideras.com and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

-

1/4

Polly Toynbee and Nick Bryant

-

2/4

Polly Toynbee speaking at the Roundhouse

-

3/4

Nick Bryant

-

4/4

Polly Toynbee signing books

Polly Toynbee

Polly Toynbee is a journalist, author and broadcaster. A Guardian columnist and broadcaster, she was formerly the BBC's social affairs editor. She has written for the Observer, The Independent and Radio Times and been an editor at The Washington Monthly. She has won numerous awards including a National Press Award and the Orwell Prize for Journalism.

Nick Bryant

During a distinguished career with the BBC, much of which was spent covering US presidential politics, Nick Bryant came to be regarded as one of its finest foreign correspondents. He has written for The Economist, The Washington Post and The Atlantic, and is now a regular columnist for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. He is also a regular contributor on the ABC. He is a history graduate from Cambridge University, who holds a doctorate in US politics from Oxford University.