Geraldine Brooks on Writing History

The voices of the unheard are always the most intriguing to me, the ones that were denied an opportunity. So where do you find them?

Hear from two-times Pulitzer Prize winning author Geraldine Brooks. Brooks' novels are complex narratives steeped in history and anchored in fact that often contain fascinating unsolved mysteries.

In conversation with Fiona Morrison from literary studies at UNSW Sydney, listen about the pleasures and challenges of writing, why she loves writing history, how she gets into her creative flow, and of course her books which include People of the Book, March and Caleb’s Crossing, and her new novel Horse.

Horse glides effortlessly across three places – 1850s Kentucky, 1950s New York City and 2019 Washington DC. From a discarded painting in a roadside clean-up, forgotten bones in a research archive, and Lexington, the greatest racehorse in US history, Horse is a sweeping story of spirit, obsession and injustice in America.

This event is presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and UNSW Arts, Design & Architecture.

Transcript

Ann Mossop: Welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas podcast. A place to hear ideas from the world's leading thinkers and UNSW Sydney's brightest minds. I'm Ann Mossop, director of the UNSW Centre for Ideas. This podcast was recorded on the lands of the Bidjigal and Gadigal people. We pay our respects to their elders past and present, whose sovereignty was never ceded. The conversation you're about to hear, Geraldine Brooks on Writing History is between Pulitzer Prize winning author and journalist Geraldine Brooks, and associate professor Fiona Morrison, and was recorded live. I hope you enjoy the conversation.

Fiona Morrison: Hello, everybody. It's my very great pleasure to introduce to you in fact, a person who needs no introduction, Geraldine Brooks.

Applause

As I was saying to Geraldine backstage, there's been a really quite marked, wonderful, deeply pleasurable interest in, and warmth about, this conversation. And, of course, that is met by the wonderful success of the novel that we're here to talk about tonight, Horse, but there's also something about the way that we hold her here, I think, and that all kinds of readers, colleagues, peers, friends from from long ago, people in reading groups, people in the book trade, there's a tremendous interest and warmth. So that's lovely to be associated with Geraldine just at the moment particularly. So journalist of wide experience, from cub reporting on the races in Sydney, to war correspondents from Middle East, and points of the compass. A writer of nonfiction, journalism, and book length work. And now the author of six distinctive novels – it’s a body of work, an oeuvre, as they say – for the most part, historical fiction. Can I choose one of the many aspects of this career that I've just summed up that are interesting, and ask you to tell us a little bit about the move from nonfiction writing to writing fiction? Why was this important or necessary? And how did it work?

Geraldine Brooks: Well, it is a very quotidian answer. I had a baby.

Fiona Morrison: A biblical answer.

Geraldine Brooks: And I didn't think that was particularly compatible with my previous life of being woken in the middle of the night by an editor in New York saying things like Khomeini has finally kicked it, get up and write something, and then go to Tehran. Or Gaddafi just bombed something, and, you know, go to Libya. So I realised that I needed a new gig. And I thought that I’d just switch to a different kind of journalism that, much to my dismay, nobody ever called me up and said, why don't you go and sit by a swimming pool with George Clooney and do a celebrity profile? They were still saying, you know, would you like to walk across the, you know, Afghan border with some Pashtun warriors? And I, you know, I'd be nursing my son and go, no, I would not. So I realized that it was time to look for something else to put food on the table. And I was incredibly lucky to win the Kibble Award for my second book of nonfiction, Foreign Correspondents, and it came with a very nice check. And the idea of that prize is to encourage women writers, and I was really encouraged when I looked at the check. And I thought, I'm gonna take some of this, and I'm going to use it to buy time.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah.

Geraldine Brooks: And see if this idea that's been banging around my head for 10 years now could possibly be a novel. And that was the story of Eyam in the Peak District, and what happened in this town, when bubonic plague arrived, and the villages took the unique decision to quarantine rather than do what everybody else did, which was flee, in a dozen different directions and spread the contagion. And I had thought maybe it was a nonfiction book, but there wasn't enough on the historical record because it was a village of illiterate lead miners and shepherds and they had not set down an account of their experience. So you couldn't really write any more than a pamphlet on the actual known history, so the only way to tell the story was to engage with the imagination of what it might have been like. And so I sat down, and I wrote three chapters, I think, and the ending. And I sent it to my nonfiction agents. And I didn't hear anything. And I thought, oh she hated it, lousy, I better, you know, better go on that walk in the Afghan mountains. And then she called back and blow me down, she'd sold it. And then I had no choice. I had to write it.

Fiona Morrison: To a deadline.

Geraldine Brooks: Well, pretty much yes. And you know, and then, you know, incredibly luckily for me, somebody wanted to read it. And so I got to keep doing it.

Fiona Morrison: And that's the book that, of course, has had a huge uptick in sales.

Geraldine Brooks: It's an ill wind,

Fiona Morrison: The year of wonders, the wonderful year. And at that moment, then, a certain kind of modality of writing history through addressing the gaps in the record, and that's the work of fiction, in your work, that from that moment, these six books emerged, and many more, of course. I want to come back to the question of the gap in the historical record as the, kind of, the challenge that you address, and the genesis point of so much wonderful work, by picking up foreign correspondence. I was looking at it in preparation for speaking to you, and I was really struck by the transnationality of that work, and it made me think a little bit about… I work on Christina Stead, and she was a powerful commentator on American life and the 30s and 40s. Though both Australians and Americans are occasionally very uneasy about her ambiguous position in that work. Are we at a point now, from your point of view, where you are a writer living in America, and it's quite acceptable and usual and kind of practicable, to have many different connections, locations and identifications, is it possible to be a worldly writer now, easily?

Geraldine Brooks: I think, you know, we grow up in this country in an incredibly privileged position compared to people who grow up in the United States. I believe that we grow up uniquely turned out towards the world, and curious and receptive to everything that comes in. And I didn't understand particularly how valuable that was until I saw the opposite, which is the incredible insularity of American society, where there's, there's a kind of a nostrum that they are so very interesting. Well, you know, they kind of are interesting, but they don't need to do what we do, which is accept all the incredible culture and richness. You know, their eyes will glaze over, if you say, I just came back from Eritrea. Whereas here, somebody will say, oh, yeah, I know, Eritrean, and they live down the block. And, and so what was that, like? You know, and I, I don't want to stereotype that it's a stereotype and it's, it's rooted in something real. If you look at American TV, foreign news is really contracted to a spec. It's very sad to me that CNN, like, you used to be able to go and see some foreign news and quite well done by some really wonderful foreign correspondent. It’s all just blather about the latest outrage of Donald Trump and three different people giving the same opinion. And anyway, that's… I don't know if that answers your question.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah. I mean, what's striking is your effortless, it seems, modality in addressing a range of different situations and a range of different historical questions. What is striking is that the Americans are happy. They love you, too. I mean, there's the love here, but the Americans are also… their insularity and xenophobia doesn't stretch to Geraldines from Sydney.

Geraldine Brooks: I had a you know, it was lucky for me when I wrote March. If I had been an American they would have put me in a box, I would have been either a Yankee or a Southerner.

Fiona Morrison: Yes, yeah.

Geraldine Brooks: And then half the country wouldn't have been interested in what I had to say.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah, that's so interesting. I had not at any point in reading March, had thought of that as a possibility. That's really interesting to hear. Such a powerful book. So, tonight, you've described your coming to fiction as emerging from or perhaps scaffolded by, gaps, or void in the historical record. Has there ever been a time when a continuous or powerful narrative available in the historical record has swept away? Have you been subjected to archive fever?

Geraldine Brooks: Oh, every book, every single book, and you know, that the risk is that you get swept out to sea. And you’re following some train of research that is absolutely fascinating, but has no business in the story that you set out to write. And so you have to really swim hard against that current, because I think you really do need to let the story tell you what you need to know and not just take something that was just too good to leave out and cram it in there. So I try and resist that. Yeah.

Fiona Morrison: I was trying to second guess what that might have been in Horse, which of course, seems beautifully structured. A victory of structure. And there were so many options, but it seemed to me Cassius Clay was one of them. And Ten Broeck was the other, of being swept away.

Geraldine Brooks: Well, they were gifts, it was a gift that… but honestly, it was the horse.

Fiona Morrison: Yes.

Geraldine Brooks: I… the idea… I stumbled on the idea, a very auspicious moment, because, you know, it was my midlife crisis, of falling in love with riding and rather ill advisedly acquiring a horse before I knew anything about how to ride or care for a horse. And then becoming so obsessed with both learning to ride and care for the horse and, and not wanting to do anything else, including my day job, which was trying to finish the book about King David, who suddenly was a very boring fellow. And, you know, it was getting rather parlous financially, and then I heard about this 19th century racehorse that had a particularly interesting twist in the Civil War period. And it was a gift. And I took that to my editor and said, next book, and he wrote me a check. And so we were all good. So it was the horse, but then I didn't know that the horse was going to lead me into you know, I think I said in the afterword, it couldn't be a book about a racehorse, it had to be a book about race, because I learned that the thoroughbred industry, which was an absolute obsession, in the mid 19th century in America, was built on plundered labor of skilled black horsemen. And then I couldn't not. I mean, I could have centered the story on these really interesting white guys, Cassius Clay being one and Ten Broeck the other, and the painter Scott. I could have centered the novel on them, but I think that would have been an unconscionable erasure of the true black history. So…

Fiona Morrison: It’s really interesting. The couple of questions I have take us to the horse and I'm not, I'm not, you know, dodging the question of race. Certainly, I want to come back to it. But in Australia and Australian history, of course, black stockmen…

Geraldine Brooks: Yes.

Fiona Morrison: In all kinds of regions, but particularly associated with, you know, labor movement protests in the Northern Territory in northern Western Australia. It's an extraordinary story. I mean, at the risk of, well, with pandemic television as my excuse, I found myself returning to a film very close to my childhood heart, which was The Man from Snowy River.

Geraldine Brooks: Oh, yes.

Fiona Morrison: And more recently, with the same excuse, I watched Farlap. Although not all the way to the end, because it's too hard.

Geraldine Brooks: It’s depressing.

Fiona Morrison: Yes. But I found more context because of your portrait of the high stakes of the American racing industry from, you know, 80 years before the events of Farlap. I'm curious about the big horse as the collecting point of a nation's interest. You know, much painted, beautiful, the very form of it, the very figure of it. But Lexington, of course, emerges in this much earlier period. And the cultural context and stakes are different. Nevertheless, is he another version of the Big Ticker? That speaks to and for a nation. Is that how you found it?

Geraldine Brooks: I think it goes back to the earliest records of human artistic creation, the first images people drew on the walls of caves were horses. We've always been drawn to them. There's an affinity there. And of course, you know, in the mid 19th century, it was an agrarian society, everybody had a horse. Or they were very, you know, one generation removed from having horses and people love competition, and, so, you know, everybody raised their horses, they used to race them down the main streets. That's how the American Quarter Horse came to be. But the national obsession was with these extraordinary four mile heat races. And if you imagine, you know, we consider the Melbourne Cup, a very long race, these were three times as long and they and the horses would do them up to three times in one day. So you're talking about incredible endurance and strength as well as blistering speed and tactics, the jockeys had to have incredible tactics, and the horses had to respond to that. So these were extraordinary animals, and I think it was a much more interesting competition. And also they didn't race them as such babies as we race horses now. I think Lexington was, he was a celebrity so extraordinary that when he died, they they ran his obituary over three issues of the racing paper, going back over every detail of every race that he ever performed in and then every, every one of his progeny, what their, you know, racing prowess was like. This horse was really beloved, people like General Custer would come to the, you know, make a special pilgrimage to the farm to admire him. And President Fillmore came to watch him race, you know, so he's a big deal horse.

Fiona Morrison: Extraordinary, as you so beautifully evoke it in this novel, that animal in the cultural imaginary in quite that way, painted, recounted, and as you suggest the animals there but the shadowy lives closest to the animal, the human lives closest to that animal, are rendered invisible. Although there's tantalizing evidence for missing.

Geraldine Brooks: So yeah, so the main character in the historical spine of the novel is Jarrett who was the horse’s groom, and he was an actually existing person who had been enslaved, was emancipated, finally, and we know this because there are records of his starting to get paid for his labor on the farm, and he exists in a painting. Unfortunately, nobody's seen this painting for 150 years, but there is an apparently wonderful painting, the best by all accounts, that the artist Thomas Scott ever did, of Lexington, in his old age being led out by Black Jarrett, his groom. And so that's what made me think about this young man and his relationship with the horse, because once you know something about horses, you understand that it's not the owner, it's not the trainer, it's not the jockey, it's the groom. It's the person that's with the horse every day, feeding and mucking out and brushing, that has an intense relationship.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah. And an affective relationship between those two, which I think I use to negotiate some of what I find very tragic about the end is that I hold with me as a reader. The work you do on Jarrett's relationship to Darley, Lexington… yeah, it's something to hold in the work, I think.

Geraldine Brooks: Well, I think it's the central love story.

Fiona Morrison: Completely. And there are resonances in Theo's relationship with Clancy, the dog.

Geraldine Brooks: Yes.

Fiona Morrison: That and I do. I do want to come to that. One of the things that's really interesting in the way that you work on the question of Lexington, is the threads of the novel pick up various ways in which the horse might be represented. So it's fascinating the surface depth relationship, which is of the painter who is thinking about depth, but Jess in the present, who is thinking about the articulation, which of course, for a literary critic, you see articulation, you think, I'm going to overreact now. Because it's about naming but also about taking apart the pieces and putting them back together. And so in a sense, do you come at Lexington through art and through science? Was that conscious? Or did you?

Geraldine Brooks: Yeah, it was very much, you know, I was attracted to the story, the historical story, and I learned about it from the gentleman from the Smithsonian, who had just delivered the skeleton which had resided at the Smithsonian, and at first, as a kind of treasured exhibit of this famous racehorse, but then as the Smithsonian's mission changed through time from being a kind of cabinet of curiosities to being a scientific research organization and an educational one. They weren't really interested in Lexington as the specific famous horse, they were interested in this skeleton as an example of Equus caballus, sitting in the hall of mammals next to a skeleton of a rat, and a fox, you know, just the species. And so the history of the particular horse had been erased over time. But the scientific business of how do you prepare bones and why, at the Smithsonian do you not articulate a skeleton any more, you carefully prepare the bones and you put them away in a drawer, so that they can be measured and sampled for DNA, and then, you know, and 50 years from now, something else that we don't know about, some other scientific method can be used to tell more about species. And that's what people are interested in now. And, you know, for me as a as a novelist, and as a former reporter, I was just attracted to the idea of writing about somebody who does that work, because I love to get up in other people's business and spend time behind the scenes and, you know, have an excuse to go into the back rooms.

Fiona Morrison: As a reader, it was wonderful to go with Jess. I mean, it was wonderful to spend time with Theo in the art, in art criticism, but the backrooms of the Smithsonian…

Geraldine Brooks: What a place!

Fiona Morrison: What a place.

Geraldine Brooks: I mean, it is just incredible. So the museums downtown in Washington on the mall are just, it's not even the tip of the iceberg. It's the tip of the tip of the iceberg. And then out in suburban Maryland, there is miles more, there's storage, pods of art, and scientific and color types of every species known to have existed, and all these research labs and scientists working on everything you can think of, from art restoration, to DNA research, and then there’s the Osteo Prep Lab, which is where I got to hang out and learn that… you know, all this high tech, high test science, with every bit of equipment you can imagine, they still use dermestid beetles to clean the bones, because that's the best thing they have come up with. They do it causing the least damage to the tissue.

Fiona Morrison: Yes. So it was the smell that you evoke, in the novel, was that what it…

Geraldine Brooks: Yes! It’s pretty whiffy in there. And they have to keep it quite humid, the bugs like it humid. So the thing looks like a gigantic refrigerator, except when you open the door, it's warm in there, and very smelly.

Fiona Morrison: It's an extraordinary journey and in the novel, from the genus horse, of which Lexington becomes the example, although they lose the content of that, through the naming process. It's a process of articulating names till you get to this horse. It seems to me important that Jarrett Lewis also acquires his name…

Geraldine Brooks: Yes.

Fiona Morrison: As a kind of profound moral arc as well, in a way. Coming back to Jarrett, there's so much to say, I think, it's such a rich seam of discussion about your interest in, and deployment of first person. I was reading the work and then we're in the ghastly business of moving house. so I got my trusty audible out. And I was very interested to see the different voices being used in the audio book.

Geraldine Brooks: Yeah, this is really amazing, because I've never had this before, but they actually have a cast read the book. So there are different voices for the different characters. And I really like it. it's the first one I've actually been able to listen to. Because usually, no matter how fine the voice actor is, there's always something that doesn't sound the way it sounds to me in my head, but in this case, it's really wonderful to have a British Nigerian reading Theo.

Fiona Morrison: Reading Theo, yes.

Geraldine Brooks: And an Australian woman reading Jess.

Fiona Morrison: I can really recommend it, everybody. I mean the book, well the book first, but that… what of course it does is, it makes me think a lot about the voice, which I think is, the voice is the access point to the past, the past coming alive through voice and how you accessed it, particularly Jarrett, because he was almost, in my mind, the furthest away.

Geraldine Brooks: Yeah, yeah, definitely.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah.

Geraldine Brooks: Yeah.

Fiona Morrison: Do you want to talk a little bit about coming up with Jarrett's voice?

Geraldine Brooks: So the first thing I did was, I took everything that I feel about horses, and gave it to Jarrett. So that was a lot. And then you have to really do the work, which is, what do we know about people in Jarrett's position? And that's where you have to dig very deeply because of course, people in Jarrett's position didn't get to write their own story, or, you know, generally speaking, the voices of the unheard are always the most intriguing to me, the ones that, for whatever reason, were denied an opportunity to become literate. And so where do you find them? And sometimes, you know, and tragically, the only place you can hear them is in court where they took verbatim testimony. And you can hear people speaking and that's particularly true for women in early colonial America, where women were always being hauled into court, and accused of terrible crimes like being a scold. One of my favorite court cases, I can identify with this woman so much, she hauled in, because she was caught abusing the guys who were supposed to be repairing her house, and they weren't doing a very good job and so she was standing in the street, giving them what for. And so they hauled her into court for the terrible crime of criticizing a man in public. So lucky, that's not still on the books, because we'd all be…

Fiona Morrison: More and more tempting.

Geraldine Brooks: But, you know, this is not funny, but what you find when you there is, you know, women who were very aware that they were getting the wrong end of the stick in this society, and they are quite angry. And dare I say it, they sound like modern feminists, and you know, people have said, oh, you know, Geraldine Brooks’ women, they are just sound like modern feminists. Well, hello, go and read some 17th century court documents, because we were not the first generation of women to know we were getting a raw deal.

Fiona Morrison: And that comes through testimony, comes through the direct… well, as direct spoken voice as you can have recorded.

Geraldine Brooks: Yeah, so I didn't find anybody like Jarrett, you know, he…the interesting thing for me as a piece of learning, researching this book, was that the skilled horseman had a very unique position within this barbaric institution of enslavement. In that, their skills were very much appreciated by the thoroughbred owners, because so much of those guys, prestige and wealth came from these horses. And they actually deferred to the expertise of the black horsemen. And that didn't mean that these men couldn't be ripped out of their families and, you know, moved against their will. But they did have a relative privilege, in that they could travel across state lines, they could accumulate property in their own name. And that allowed many of them to eventually buy their own emancipation before the Civil War. So, they were not likely to end up in court at all. So I just had to rely on some very scanty sources, there's a couple of oral histories, and you have to take those with a big grain of salt because the oral history is being taken by a white person. So how much can the black interlocutor really say about you know, bad treatment and so forth. But you learn, you learn things. And then in letters, the thoroughbred owners write, you learn about the life of the black horsemen, because they're describing you know, I'm sending you my Hark because he's an expert at this or that, you know.

Fiona Morrison: Their mobility… so that the imaginative work that is so empathetic and important, in and around Jarett, is about imagining that strange and interesting position of some power, but enslavement.

Geraldine Brooks: Well, he’s got the advantage of doing work that he loves, which so many enslaved people didn't. And so that gives him some agency. And then you have to imagine what that would be like if that was stripped away for any reason. And then the precarity of his situation and not having control of his destiny until quite late in his life.

Fiona Morrison: Yes. And that's certainly a narrative drive too, for the reader, who if you happen not to know what happened to Lexington, I was constantly worried about what was going to happen to Lexington and the blindness. And you don't know what happens to Jarrett that, that that is a narrative drive too. There's a lot to be reading on for but that is one, the safety in and around precarity of those two. One of the audience questions that has come in, picks up some of this material and asks us, sort of, a situated question from here. So from the audience, in your new book, you face up to Black/White relationships in the US in a way that is illuminating for me – this is the questioner – especially the late interaction with Leo's neighbor. What can the UNSW community take from your book in terms of actions to decrease discrimination against Australian First Nations peoples?

Geraldine Brooks: So yeah, so what happened was once I realized that I would be writing about race in the 19th century, but that I was also going to have this modern strand of the narrative in the present time, around the science, because I wanted to write about the science, I thought I cannot leave the question of race in the past as though it's something that's over and done, because it's so not. And that was a drumbeat that was happening the whole time. I was working on the book because George Floyd was murdered by Chauvin and Breonna Taylor was shot in her bed, and Ahmaud Arbery, was gunned down just for going for a jog and, and on and on and on, and my, you know, friends and neighbors on Martha's Vineyard, who are a very privileged, you know, a very talented segment of the black community, I have learned, you know, from knowing them over the years that that is absolutely no protection from the things that come at them, because of the color of their skin. You know, people will be pulled out of their own fancy car by a racist cop who doesn't think a black person would have a fancy car like that, or my neighbor, Skip Gates, Professor Henry Louis Gates, who, you know, absolutely esteemed Harvard professor and also TV star, dragged off his own porch in handcuffs for the crime of trying to open his own front door one night. You know?

Fiona Morrison: Shocking.

Geraldine Brooks: So this is the reality, and it just drives me crazy. when people say, why are people so obsessed with slavery, that's over and done with. It is not. You know, in living memory, schools in Virginia, closed rather than integrate. And that deprived people who were teenagers, the year I was born, got four years without any education. What are the costs of that in a human life, that's still being paid. But people are not able to do the simplest thing to acquire the ability to rise into the middle class, which is buy your own home, because they were denied credit by banks. And that was, you know, it was completely blatant and open redlining. And you know, everybody needs to know these things. And the question is, what can we do here? We need to know these things, too. We need to face up to the the structural discrimination faced by First Nations people. And to me, one of the most pressing issues is Indigenous literacy and closing that gap for the children of this country. It is disgraceful that there is still such a wide gap in literacy between First Nations kids and white kids.

Fiona Morrison: Yes, thank you for that. That's a wonderful insight into the moment of writing, which is, often it seems the charge of writing history and I think there's a character who refers to this, Leighton horse, and you're going to tell me what it is. And I'm reaching for it, writing history is about, in a sense addressing social change. So that the right writing of historical fiction is always about the present.

Geraldine Brooks: I think, you know, I think it is, I think it is. And this was something I got from my late and much missed husband because he was very, he was the real historian in the family. He said, I went over to the dark side when I started making things up.

Fiona Morrison: But grateful you did.

Geraldine Brooks: He was so exercised by the reverberations of history and how history is not finished. And I think, you know, his book, Confederates in the Attic, which was about the unfinished legacy of the civil war in America. Everything that he wrote about in 1996, is coming to fruition right now.

Fiona Morrison: Yeah. So Tony Horwitz’s wonderful book, Confederates in the Attic. I remember reading it and thinking, surely not. What that brings me to, is a question that I have as a reader situated here, which is, the other country, which seems to be the South, something you and your late husband were both, you know, well versed in, is there a is there a cognate region in Australia?

Geraldine Brooks: Ah, I hope not. But it’s not, I mean, I think it's too simple to say the South, because within the South, there are oases of extremely progressive cities, like the city of Houston, extremely progressive, Austin, Texas, extremely progressive cities. And conversely, this kind of archaic conservatism has spread into the Midwest, for which I blame, in large part, the Democrats for abandoning the working class. And just leaving them with nowhere to go, as the Democratic Party fell in love with Wall Street and big money, and, you know, just let the union movement be completely destroyed. So it's not just North and South, it's red America and blue America, and it's a spotty map. And so you can't really simplify it like that. So used to be, when I was coming up, we had Bjelke-Petersen…

Fiona Morrison: Yes.

Geraldine Brooks: To kick around. And Queensland would have been the cognate. But I don't know. No, I don't think so. Any more.

Fiona Morrison: No. No, the map’s different isn't it? But in a similar way too, which is, that there are pockets of progressive kinds of thinking in all kinds of places.

Geraldine Brooks: Well, you know, I love that Western Australia just gave Morrison the boot comprehensively. So if Western Australia can do it, yay.

Fiona Morrison: Extraordinary. Campaign launch in Western Australia, that's it. One of the things that impresses… one of the many things that impresses me about the work is that despite the fact that it operates through this braiding of voices, as a small choir of voices that emerge, and this is connected to the first person interest, the mode that you adopt, you still sustain an enormous amount of time and space. And, broadly speaking, of course, the novel works with its chronological logic, both in the past 1850 to 1865, and in the present of Jess and Theo's meeting and relationship. Was there an architecture to where the voices came, that you were conscious of? Do you work architecturally, or is it instinctive, poetic…

Geraldine Brooks: This was a little different, because I was just taking out on trust that these three strands were somehow going to come together. And it took a long time to see how that would be. And I was starting to get a little bit desperate at one point, like, ahhh! What is the connective tissue that is going to bring these… and then it starts to emerge, and, boy, you know, what a relief. You know? But it comes from doing the work, it comes from sitting with it every day and writing and rewriting and thinking and rethinking and restructuring, and you know, so it's, it's all about heavy revision and not being wedded to one particular version.

Fiona Morrison: And I was admiring that, particularly that, the work coming into play there, then, as you get late into the work of the Civil War disruption, that that is just seamlessly managed, there's no flagging, it's an epic, in some respects, because of the time and space of the work. But as you come to close it, it is beautifully managed. So with those interleaved pieces I was having fancies of a kind of associative logic too, there's a kind of poetic logic sometimes, where the voices start to work, both together and even more distinctly as Jarett comes into his own name. One of the questions that an audience member has been very interested in, and this connects back to writing, writing history and the way in which it's inevitably a question of the present and the past in relationship. Are there any moments, events or stories from Australia's rich past that might inspire a book?

Geraldine Brooks: Yes. I started one, which was going to be about Jane Franklin, the great explorer and governor's wife in Tasmania, and she intrigued me so much. And then I abandoned it for two reasons. One was that she kept a diary, and she wrote down everything. So there wasn't any room for me. And then also, I couldn't, I couldn't come to terms with any way… you have to, you have to understand a character as they understand themselves. So, you know, I don't think anybody wakes up in the morning and says, I'm a really lousy person, and, you know, I'm going to do a hideous thing today, everybody tells themselves a story about why, what their actions are doing is well motivated, I think. And I could never understand how she could have adopted Mathinna, and then abandoned her into a system that she knew was so cruel, and that she had campaigned against. And if I couldn't understand her, then I couldn't write her. And so I had to give that one up. But there's another woman who intrigues me a great deal. I have to find something that's not totally bleak, because Australian history is so painful. I mean, we really, it was such a tough place, and we did such terrible things to the people and the land. And I just… I find it so much easier to write about other people's sins than our own. So, but there is one story that intrigues me a great deal and is not entirely bleak. And I think one day, I hope I'll get to tell that one.

Fiona Morrison: So, to be revealed.

Geraldine Brooks: To be revealed.

Fiona Morrison: Very good. Yes, watch this space. Coming back to the texture of Jarrett's relationship to Lexington, to Darley, then Lexington, were introduced to him early through, in a sense, his his father's gaze, and Harry, looking at Jarrett and noticing his extraordinary talent, his capacity to communicate with the nonhuman other, with the horse. You said earlier that that, in a sense, was drawn from your experience, do you want to talk a little bit more about the animal-human relationships in the book?

Geraldine Brooks: Well, animals are incredibly important to me, I get enormous joy from them, not only my companion animals, but through promoting biodiversity, on my own land, and then within my community, working on the Conservation Commission, it's just, you know, this will be a very lonely planet, if we keep going the way we're going, you know? We will be alone and then we won't be because of the web of life. So it's just incredibly important to me. And then the joy I get, you know, from my dogs and my horse, and it's always been dogs for me, but then horses came along and horses are such a different relationship because humans and dogs are on the same side, we're both predators, we’re both looking straight ahead for our next meal, whereas a horse is the next meal, you know? And a horse's eyes spanning this huge, more than 180 degrees they see, you know, they can see all the way around them, and they have to because something could be coming to eat them. And then to form a bond of trust between a predator and a prey animal, it's harder, and when it happens, it is just so rewarding. You know, when I first got my horse she used to run away from me, I could not catch her. And now she runs straight towards me and we lean into each other and there's just so much comfort in it. I get it. I hope she does.

Fiona Morrison: They’re powerful. I mean, I lived for a while in the southern highlands. That's as close to a horse as I've more or less… apart from my passion for The Man from Snowy River, the closest I’ve come. But um…

Geraldine Brooks: Can I just say one thing about that?

Fiona Morrison: Please do.

Geraldine Brooks: No one in their right mind gallops a horse downhill. I’ll just leave it there.

Fiona Morrison: Well, Geraldine, I have to share with you that as part of research for talking to you, I found myself listening to Tom Burlinson talk about the fact that every year he goes back to Snowy River, talks to the master of horse and goes on a ride for a week with fans of the movie.

Geraldine Brooks: And I bet they don't gallop downhill.

Fiona Morrison: They… no! They said, did you do it? He said, yes, I definitely did it. Was it as dangerous as looked? No! And I thought, how is that true? So there's a whole side conversation about The Man from Snowy River fandom…

Geraldine Brooks: I also… there's a side conversation that we haven't had about the treatment of equines.

Fiona Morrison: Absolutely.

Geraldine Brooks: And a lot of horses died during that shoot. So it might not have been dangerous for him. But it was dangerous for some of those horses.

Fiona Morrison: Yes. And what comes up through your work is the persistent note of the terrible risk in 1850, and in 2020.

Geraldine Brooks: It’s worse now! I think it's worse now because particularly in America, I mean, it's way past time for reckoning about how racing is conducted in the United States. And I know that it's true here, there's been a lot of deaths of horses in the Melbourne Cup and I hated being the racing cadet because I saw so many horses die on the track. But in the United States, they have practices that are completely banned in other countries. You know, there's there's so much room to improve equine welfare. And also, you know, they waste these beautiful animals, if they're not winners, they're often discarded at the age of five. And my horse has a pasture mate who's an off the track racehorse named Screaming Hot Wings. And Screaming Hot Wings just had his 33rd birthday. So when you realize that a racehorse has so much to give, I mean, he's still sound, we still take him out trail riding. He's a lovely, lovely companion horse, and he's been loved and cared for. And this is what a horse can be. Not something to be just tossed away.

Fiona Morrison: So framed in this extraordinary act of empathetic imagination, the reader comes through and to questions of race, questions of the animal Other, questions of gender with respect to various things that Jess has to negotiate. Broadly speaking, then, the book has experienced terrific success, and I wondered how you saw the success of this work? I mean, all of your work has been successful, but this one…

Geraldine Brooks: I'm really, you know, I'm incredibly relieved, because I thought that there was a much greater than 0% chance that I was walking into a… as a white woman writing about black lives. And I'm just incredibly encouraged that black readers have thought that I've done the work okay.

Fiona Morrison: And that's what's coming through in the reviews, it seems to me, which is that there's an enormous… it's like the steadiness and patience of Jarrett's voice, the thing I admire so much in this work, which is that you walk so steadily and carefully into that space. And the reviews seem to me to be answering that they're steadily and carefully seeing the work, the work of imagination, but also the research.

Geraldine Brooks: And, I think, you know, I'm in empathy, and there was a moment, I think, when people were inclined to… and appropriation is a real thing, and I'm not going to minimize it, and I'm not ever going to come out and wear a sombrero and make fun of that, because I believe that we really need to have that conversation and that reassessment about this space for other voices. I hope that people will read my book who wouldn't otherwise engage with this material, who wouldn't pick up, you know, a book by a young author that they didn't know and, you know, hopefully I can do some work in that space, provided, you know, I do it respectfully, and if I didn't do it right, I'll hear about it. Luckily, so far I'm only hearing about it from people who think I've been very unfair to the police and to Fox News.

Laughter

Fiona Morrison: It's very, very tempting to respond to that. So having… with my eye on the time, I'm having to put aside a variety of questions I have concerning stopwatches, Jackson Pollock, and all points North, East, South and West. There's a lot of audience interest in your next project broadly conceived.

Geraldine Brooks: Yes. And I wish I could tell you about it, but I can't. It's happening. And it's not fiction, and it's set in Australia. So that's all I'm gonna say about that.

Fiona Morrison: It's not fiction?

Geraldine Brooks: It’s not. Not the next one.

Fiona Morrison: And it's set in Australia.

Geraldine Brooks: Yes.

Fiona Morrison: Any more advances on that Geraldine?

Geraldine Brooks: Nuh. Not a thing.

Fiona Morrison: None at all.

Geraldine Brooks: I would if I could. I just, I can't.

Fiona Morrison: Yes. It's the moment where I, reluctantly, I have to say thank you so much for joining us tonight. There is a fantastic feeling in this room. And I hope everyone will join me in thanking Geraldine Brooks for coming tonight.

Ann Mossop: This event was co-presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and UNSW Arts Design and Architecture. Thanks for listening. For more information, visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

-

1/5

-

2/5

-

3/5

-

4/5

-

5/5

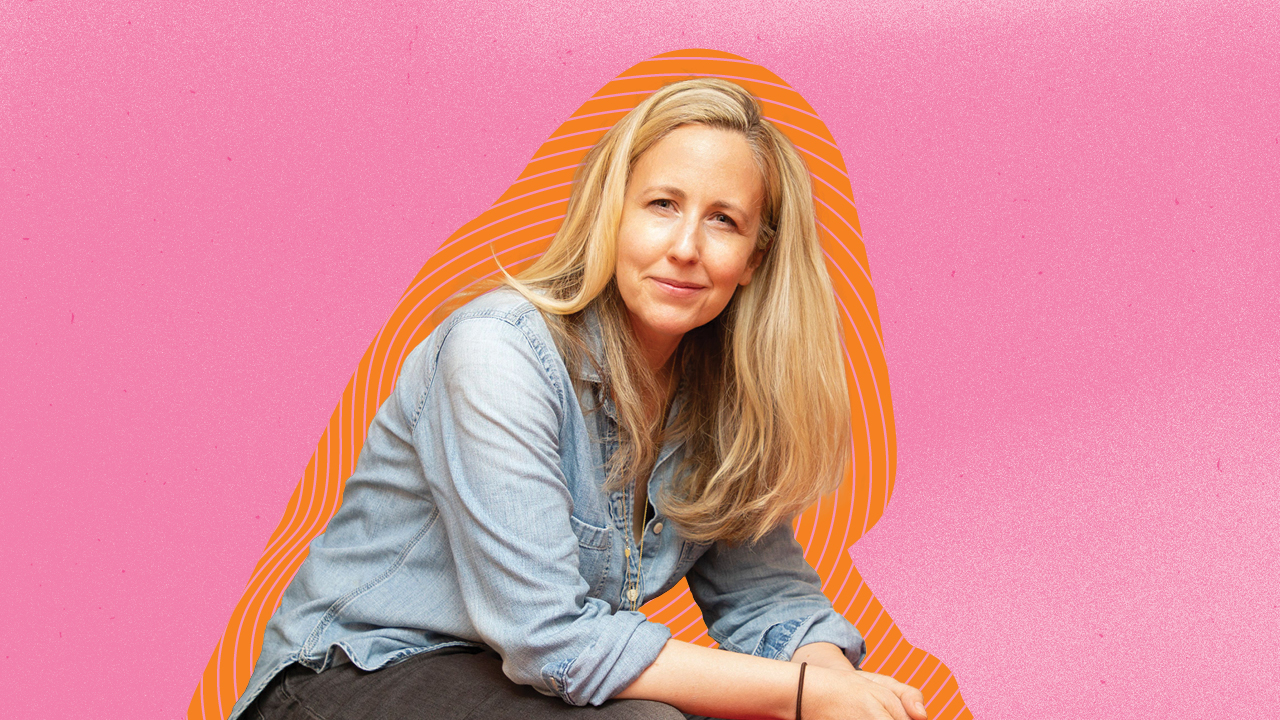

Geraldine Brooks

Geraldine Brooks AO is the author of six novels, including the recent New York Times bestseller, Horse, and the 2006 Pulitzer Prize winner, March. Born, raised and educated in Sydney, she worked for The Sydney Morning Herald, the National Times and The Wall Street Journal, for which she covered crises in the mideast, Africa and the Balkans. Her non-fiction works include Nine Parts of Desire and Foreign Correspondence.

Fiona Morrison

Fiona Morrison is an Associate Professor in the School of the Arts and Media at UNSW Sydney, where she has taught and supervised in the areas of postcolonial and world literatures, Australian literature and women’s writing. Her recent books include Christina Stead and the Matter of America (2019), Time, Tide and History: Eleanor Dark’s Fiction (2024) co-edited with Brigid Rooney and Thinking for Yourself: A Handbook for Interesting Times (Simon and Schuster/Ventura, September 2025) written with Michael Parker. She is currently working on a monograph on Henry Handel Richardson’s transnational fiction.