2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege

If we're talking about a 'reckoning' in 2022. More broadly, citizenship – it isn't just about your passport and your ability to move in and out of the country. It's about your place in the political community, having your voice heard and being part of the decision-making process.

Government agendas are not always shaped by what governments want to do, sometimes government agendas are shaped by what citizens get together and decide to do.

Australian voters ousting a nine-year-old Coalition government. A step towards instituting a First Nations Voice to Parliament. Grace Tame. Entrenched structures of authority have been challenged at home and around the world this year. But what will the impact of these momentous events be on the way we live, and the way our domestic and international parliaments govern? The Conversation’s latest collection of insightful essays from leading thinkers, 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege, unpacks this very question.

Hear Tim Soutphommasane, Professor of Practice at University of Sydney and Michelle Arrow, Professor of Modern History at Macquarie University as they explore the potent forces that continue to shape our world and how those with the privilege of power don’t always prevail in a panel discussion chaired by The Conversation’s Senior Editor, Sunanda Creagh.

To purchase the book, 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege, head here.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and The Conversation.

Transcript

UNSW Centre for Ideas: The conversation you are about to hear – 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege – features Tim Soutphommasane, Michelle Arrow, and Sunanda Creagh, and was recorded live.

Sunanda Creagh: Thank you, everyone for coming along tonight. Now, I just wanted to say that welcome to tonight's event, which is launching our book 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege. This event is presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and The Conversation. My name is Sunanda Creagh, I'm a senior editor at The Conversation. And I wanted to start by acknowledging the Bidjigal people who are the traditional custodians of the land on which we're meeting today. I also wanted to pay respects to elders past and present and extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are with us here today. So The Conversation, as you may know, is a website, we publish analysis and articles by the leading academic minds in Australia. So we're always going to the top thinkers and scholars to help us better understand issues in the news, issues in policy, and the world around us.

Every year, we produce a book showcasing the best of the essays that we produce every year. And this year's book is called 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege. And it's really drawing on those two themes which were such a big part of the year that we've just had. So that book is what we're launching tonight. And we're here joined by two academics who are featured in the book, tonight's star studded panelists. Now, you might have come tonight expecting to see a few more people on the stage. And I should just mention we’re down a couple of numbers. We were quite excited to have Professor Bronwyn Carlson, a Professor of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University, here tonight. Unfortunately, she's unwell and couldn't make it. Another person who is unwell and couldn't make it was Professor Richard Holden, who is a Professor of Economics at UNSW. Both of those authors are featured in the book and I really urge you to go and read their essays, very, very interesting essays.

Let's talk about who we do have here tonight. So my first guest here is Tim Soutphommasane who is a Professor of Practice, Sociology and Political theory. And a Director of Cultural Strategy at the University of Sydney, is a political theorist and a human rights advocate. And from 2013 to 2018, Tim was Australia's Race Discrimination Commissioner. His thinking around patriotism, multiculturalism, national identity, has been influential in debates in Australia and in Britain. And he's the author of five books, most recently on hate, and has been a columnist for The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The Weekend Australian. And I'm also joined by Michelle Arrow, a Professor of History at Macquarie University, and a fellow of the Whitlam Institute, author of three books, including The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia, which won the 2020 Ernest Scott Prize for history. So thank you very much for joining us tonight.

So we're going to start with a few questions up here. But as I said, please do feel free to send in questions via slido and I will look at them on the screen and ask them as they come in. But Tim, I thought perhaps you could get us started. You're in this book writing about diversity and the makeup of the new, relatively new, Australian Parliament. You know, we had the election of people like Sally Sitou, Michelle Ananda-Raja, Sam Lim and Zaneta Mascarenhas. We also had, you know, Gordon Reid, Jacinta Price. So a lot of people said, This represented some progress towards a more multicultural and more diverse parliament. But I'm wondering, what do you think that will… to what extent does this represent a reset?

Tim Soutphommasane: I would say that, broadly speaking the election in May, and it feels like an eternity ago now does represent a significant reset to our politics. And we've seen some of that coming through the political debate and the parliament already in these first six months. And men, many would say that it's a welcome reset to it was striking to me in the immediate aftermath of the election, that much of the commentary focused on the teal revolution and the injection of gender diversity in particular into the Parliament. And, again, it feels like a long time ago now but think about the issues that were driving the teal phenomenon. The concerns about climate change the concerns about government integrity, and not least, concerns about harassment and the treatment of women in workplaces. So that's where much of the commentary immediately after the election landed. But looking at the parliament from my perspective, I was struck by the different kind of injection of diversity we also saw alongside that which is, of course, around our ethnic and cultural diversity. Now Australia's parliament for a long time hasn't reflected Australian society. And you could make this criticism on a number of measures – on class on occupational backgrounds, certainly the case when it concerns ethnicity and cultural diversity. Australia's population today has an estimated 24% of people who are from non-Indigenous and, sorry, non-European and Indigenous backgrounds, but you don't see a quarter of our parliamentarians coming from such backgrounds. In the last parliament, barely 5% of parliamentarians in Canberra had such backgrounds. So we're not talking about missing the mark. When it comes to representativeness by the breath of a hair here we're talking about a very wide miss.

So many watching the election in May worst struck certainly I was by the new levels of diversity that that were that was elected. About 15 of the 227 MPs and Senators in Canberra can be described as having an Indigenous or non-European cultural background – the big question is whether this is a sign of things to come, or whether this is just a one off or an aberration, bearing in mind that many of those elected from those backgrounds were elected in marginal seats that they weren't expected to win. And, and many of them indeed, from Western Australia, funnily enough, so whether or not this will be a sign of a more permanent shift in our political culture remains to be seen. So we've seen a reset, but we're not yet seeing a definitive change to our political culture. So I guess there's an element of caution that I'd advise here.

Sunanda Creagh: And not yet an accurate reflection of broader Australian society.

Tim Soutphommasane: No, that’s right, I mean, we're still some way off. We're talking here about a level of representation that is still far short of the 24% figure that I cited. One of the positive aspects of this is that when you think of Indigenous representation in the parliament, yes, you're seeing a very healthy level of representation there. Something slightly better than what the proportionate representation of Indigenous backgrounds would look like if you were to transplant or think about the overall look of the Australian population and what it would look like if you were to have it there in the parliament.

Sunanda Creagh: Mmm, Tim touched there, briefly, on one of the big issues driving that teal vote, which is that, women's anger, and this is the exact issue that you're featured in the book talking about Michelle. You talk about the march for justice, that real upswell of women's rage around issues around safety, abuse, harassment assault. Now, we should say that upfront, we cannot discuss the specifics of the Brittany Higgins and Bruce Lehrman case, but we can discuss the impact that Higgins and Grace Tame have had on the debate. So what is the impact? We had that big upswell? Where did it get us? Where did it lead to?

Michelle Arrow: Yeah, I mean, I think you can draw a line between Grace Tame being made Australian of the Year and that speech that she made when she was awarded that honor, and the kind of election of the teals in in May 2022. Because I think one of the things that you don't, it's not immediately apparent, I think when you look at all the teal candidates, is all the work that was going on behind the scenes from a number of you know, hundreds of women in particular who were very active, very exercised, I think, particularly around the march for justice, I think the march for justice energized women across a number of different age groups. And you saw both young women who were part of that March and part of that activism, but also older women, and they're the ones I think, who are often kind of running those community based campaigns around the teal independents. So I think, you know, if we look at the sort of timeline, Grace Tame makes that speech, she's Australian of the Year. She was very, I think what was so powerful about Grace Tame is that she refused the sort of cultural script of shame around survivors of child sexual abuse, in particular. She kind of said, I'm not ashamed, I'm not going to be ashamed. I'm going to talk about it. I'm going to advocate for survivors. And that was tremendously powerful, I think both for men and you know, male and female survivors, but it was also the ignition point that encouraged Brittany Higgins to go public. With that story. It also then sets off other kinds of disclosures that you know, remember in March 2021, there were just stories everywhere.

Michelle Arrow: Around the parliament and the kind of treatment

Sunanda Creagh: Canberra culture

Michelle Arrow: The Canberra bubble, all of that kind of stuff, became just, you know, it was sort of in the news cycle for weeks and weeks. And then of course, we then see the march for justice. And then I think what happened after the march for justice was that people got organized, you know, that there was a real, and I think it's interesting in the teal campaigns, a lot of it wasn't necessarily foregrounding gender equality, they were really foregrounding integrity and government and the question around climate change, but implicitly, I think in their, gender, in the ways that they talked about the kinds of virtues and values that they would bring to Parliament, they were kind of echoing very old style rhetoric that women have been using to justify their participation in public life since women got the vote. You know, women have this quality of decency and virtue. And it was interesting that a lot of the teals talked about, they felt duty and responsibility to run, you know, I remember Zoe Daniels’, great, “If not now, when? If not me, who?”, you know, like this idea that they had to take a stand for the sake of their children, for grandchildren to save the planet to make sure that, you know, there were some integrity measures introduced into the parliament. So I think that we can draw a direct line. And I think we can also say, in the ways that Labour ran its campaign in 2022, it was a kind of feminist campaign in all but name, it was very much centered around care. And I think, again, that was appealing to those women who had been, had experienced the brunt of the sort of burden of care during COVID, and all the lockdowns. And then, you know, delivering to those women, I think, has been a really important part of what labor sees its role as a new government. So I think you can make an argument that it really transformed, you know, Australia's political culture, that moment.

Sunanda Creagh: We're talking about such big issues here, you know, government integrity, climate change, women's safety, and so on. You know, it wasn't that long ago that, we the public, debate was focused on what was really described as sort of culture wars stuff, you know, not these huge issues, almost like a distraction from those big issues. I mean, Tim, when you were the Race Discrimination Commissioner, the debate was squarely focused on 18C, and the reform of the Racial Discrimination Act. I mean, do you feel, Tim, that we've moved on from those cultural wars, and that we've had a bit of a political reset more broadly? Or do you feel like this is a temporary lull because we've got a new government and there's a new platform, and then those issues will come up again?

Tim Soutphommasane: I'm sure that the culture wars won't disappear entirely, but the intensity of its prosecution is probably abated. And that's because it's not really something that I would imagine being top of mind for Anthony Albanese and the Labour government right now, nor does it fit with the temper of the time. So for some of the reasons Michelle has explained, I would say that right now, the main reference points for political debate are geopolitics and the economy. We were living through the consequences of Putin's invasion of Ukraine and the effects that it's having on power prices and the like. You'd need only just think about the G20. summit this week and questions about China's rise and how Australia responds to such issues, will continue to dominate a lot of policymakers' attention and thinking.

And then you think about the reality of the economic challenges that face the country right now. For a generation, if not two, inflation seemed to be a problem of the 1970s. Low interest rates seem to be the new norm. Now we're being challenged with a very different reality. And then any government that doesn't try to provide some answers to these questions, will, I think, be judged very harshly by an electorate that is looking at higher power bills, higher costs of living, higher mortgage repayments. So I suspect, as it is, in many other countries at the moment, the economic realities combined with geo-political challenges are going to define our debates in a way that the culture wars will not.

Sunanda Creagh: Well, speaking of hard realities, I mean, there's, you know, a lot of these policy issues that you touched on as well, Michelle, you know, around childcare, you know, jobs, the jobs summit, which we've had. There's sort of an energy around policy reform. And we have a government which has signaled it is eager to prosecute its policy platform. Yet it's faced with this big problem, which is the structural deficit, you know? These expensive programs at a time when our budget is in need of repair, to some extent. So how does the government – I'm interested from either of you – how does the government solve that particular chestnut?

Michelle Arrow: Yeah, it's really tricky, isn't it? Because they have come in promising a set of, you know, policies that were designed for better times, you know, for example, the stage three tax cuts are the obvious one there. And, you know, it would be smart to unwind those because they do help create a structural deficit, they overwhelmingly favor high income men, they don't, you know, necessarily help the vast majority of the population. And they are, you know, the government does need money to do some of the things that they want to do. There are, there's been a sort of systematic underfunding of a number of things. I mean, I've been in my role as the Vice President of the Australian Historical Association, we've been doing some advocacy around the National Library, the National Archives, you know, all of these institutions that have seen their funding over the last decade just deteriorate to the point where they're barely able to function. And where's the money going to come from? You know, it's not at all clear where that's going to happen. So I think that, you know, threading that needle, and perhaps, you know, unwinding those in a way that doesn't look like a broken promise, I think is going to be really complicated, but probably really necessary.

Yeah, I mean, I think that's one of the most important ones. And I think also, you know, that there will be starting to be calls for I mean, at the moment, the focus seems to be on things like workplace participation, childcare, those issues. But I do think at some point, they're going to have to grapple with the question around what to do with job-seeker payments, you know, those, raising those to a level that is not so you know, keeping people well below the poverty line, and again, where's the money for that gonna come from?

It's also disturbing to see the way the NDIS is being discussed, because we saw, you know, as the robo debt Royal Commission is unfolding at the moment. And the kind of, the way that the people who were targets of robo debt were really being talked of as burdens on the system, you know, undeserving of their payments. We're talking about NDIS recipients in much the same way at the moment. There's a lot of political debate around, oh, it's a big blowout, and it's going to cost a huge amount of money, and how are we going to pay for it and all of that sort of stuff. And I think, again, the government needs to kind of retake control of some of that narrative, I think, to frame that correctly as an investment that benefits a large number of people. So I think, you know, they are dealing with a lot of things that were designed for a different economic set of circumstances and unfolding… I mean, it's like 2008, 2009, you know, labor gets into power, there's a global financial crisis, which, you know, forced a large reconceptualization of what they were planning to do, and kind of limited what they could do.

Tim Soutphommasane: Well, I think there is a reset happening. And sorry, to return to that ‘R’ word, which is better than the other ‘R’ word, recession. But you saw in the budget that was handed down by Jim Chalmers, that you didn't see a widespread splashing of cash, which has become a default expectation of many people when it comes around to budget time. And when people do face challenges. The default expectation is, well, the government's got to do something, the government's got to give a handout here, or make a payment or do something to ease the burden. And what strikes me with the approach that Jim Chalmers and the Labour government’s taken with this first budget, is they've been very clear that they're not going to go down that path. That Charlmers is trying to tell a very different story and really taking the time to explain to the Australian public that there's a new economic reality, there are storm clouds gathering. And the best way of controlling cost of living rises is going to be to get on top of the inflation challenge.

But ultimately, fiscal arithmetic boils down to two things, it boils down to revenue and expenditure. In order to get budget repair, you've got to do either, or combination of two things, one, raise more revenue, two, cut your expenditure. And I suspect there's going to need to be a more sustained conversation around revenue in particular. So the stage three tax cuts is going to be central to this debate. We're talking about billions that could be saved there. And it wouldn't surprise me if there is a deliberate move to take this to a future election and make that part of an election contest. It's very clear already that the Labour government does not wish to break promises that it made at the last election. And if it is going to depart from its current policy settings, it will seek permission from the electorate to do so. Because the big fear at the back of, I imagine, many Labour politicians' minds is, the kind of scare campaign that was run so successfully against Labour in 2019. And this is the old bogeyman of Labour not being good economic managers, squandering Australia's wealth and so on.

But if we move away from the politics for a moment and think about the policy questions, I would say this, you know, we should be having debate about whether, for example, we should, we should have super profits, taxes on on some of our mining companies, who, and natural resources companies, who may be making a windfall right now from the export of gas. These are questions that have been deferred and haven't properly been debated in public. Right now seems to be a good time to be having that debate, given what we're seeing with power prices and, and the pain that many people will be starting to feel in their power bills and the like, very soon, if not already.

Michelle Arrow: And I think, sorry, I was just going to add, too, the industrial relations debate does seem to be something that's long overdue as well. I mean, I think people can be very aware that everything's gone up over the decade, except their wages. Profits have gone up and wages have not. So I think that the current industrial relations debate is a pretty important policy reset for a Labour Government, obviously, to kind of restore some of the balance in the industrial relations system that's been very much weighted towards employers rather than to employees.

Sunanda Creagh: Great, we've got a few questions rolling in. So I might just go to one of these. There’s an interesting one here, noting that the world population’s just reached eight billion, you know, that's just happened this week. Most people alive today live in Asia. How and when do Western societies step back from their power and privilege? And what might global norms look like in the near future? I mean, I did think this does speak to a question, a very live question about geopolitical power shifts. I don't know if you, Tim, have any thoughts on this?

Tim Soutphommasane: Oh, well, yeah, we've got to wrestle with this, right? And just think about the G20 summit this week, and the optics of that. 20 years ago, the leader of the People's Republic of China probably wouldn't have featured in the commentary about world summits and global diplomacy. Xi Jinping is now one of the central players in global politics, and rightly so. So I would say that the debate, or the discussion, that we might have around the rise of China and how Australia responds is very much part of that question of how we reconcile with new realities. The reality is that many of us would have been accustomed to, certainly me, while growing up, would have been to think of the United States as the undisputed superpower in world politics. There’s a clear challenger emerging, and that has emerged now, and the question is going to be, how will these two powers reconcile this? How would they work this out? You know, is it going to involve conflict? Or can it be managed? And that is a central question of our time. And I don't think any of us really know just yet how it's going to play out.

Sunanda Creagh: So I just wanted to talk briefly about the Voice to Parliament, which we haven't quite touched on yet. I had hoped that Professor Carlsen was here, could speak a bit about this. But, you know, it's a big issue that we are all going to be asked to vote on sooner or later, there's going to be a referendum around this issue of Voice to Parliament. I'm interested in what you see, as the prospects there, you know, Australians have a record of often rejecting, you know, proposed changes to the Constitution.

Michelle Arrow: Yes, it's an interesting question, I think, as to how that's going to play out. I mean, I think a lot of historians have drawn the analogy to 1967. That 1967 referendum to, you know, amend the Constitution around Indigenous Affairs, was seen as, you know, it had an overwhelming success rate, I think something like 91% of the Australian population voted yes, in that referendum. So I like to think that it might be a repeat of 1967. And I think that a lot of people, if you've heard this statement and read the Uluru statement, I think it's almost impossible to disagree with it. It is such a beautiful piece of rhetoric, it's incredibly powerful. And I do think that people do have a, there is a strong reservoir of goodwill, I think, to grapple with what that really means and to acknowledge the long history of indigenous occupation and ownership of this continent and to understand that that does confer a significant, and particular rights, on indigenous people. That said, I think, while the government has put a lot of energy into putting that front and centre of their political rhetoric, you know, it's the first thing Anthony Albanese said when he was, you know, in his victory speech on election night. I feel like in some ways, the debate has gotten a little way on them, and I think that maybe it hasn't… you know, there's a lot of voices in that debate. There was Shaquille O'Neal, and then there was, you know, that we've got, you know, voices within the Greens Party who are kind of contesting the order of Voice Treaty Truth, despite the fact that Voice Treaty Truth is, in that order for a reason, you know, that it has to be done that way. And, you know, there are lots of advocates who will explain why it needs to be done in that way. But I worry that there's also a small but vocal racist minority who may well kind of mobilise a noisy, ‘No’ case. I do think, though, that most Australians will end up supporting the Uluru statement and supporting a referendum. And I do think there will be, I think it might, if we think back to the same sex marriage plebiscite, I think there was a noisy minority who sought to stymie that change. But I think most people will feel that as if they want to be on the right side of history. And I think that voting yes, is being on the right side of history, in this particular case.

Sunanda Creagh: Tim, any thoughts on Voice to Parliament?

Tim Soutphommasane: I mean, probably agree with Michelle there. I agree, there is widespread goodwill on this. But we should never underestimate the difficulty of getting a proposition passed at referenda. You need a majority across the country, but also a majority of the states voting in favour of a proposition. And the big question is whether there will be greater scrutiny and greater questioning of constitutional recognition once a date is announced. And once campaigning begins, because we know that there is arguably an instinctive conservatism to the Australian people, as demonstrated by the results of referenda and if the proposition isn't watertight and argued compellingly, and clearly, if there are sources of division, and Michelle has already mentioned a few of those sources of division, then the risk is that it doesn't turn out like 1967, but it turns out like 1999, and what happened with the Republic referendum, again, involving a proposition which related to an issue where there was majority support, and majority of people in 1999, wanted an Australian Republic. But we didn't see that referendum proposition getting up, the obvious distinguishing feature between 1999 and today, of course, is that you've got a government that is in support of change that will be driving the process. Whereas in 1999, you had John Howard and his government not supporting or in the case of John Howard, in particular here, not supporting a republic, and designing a process that focused on the particular model of Republic. So lots of questions still to be asked. But I agree with Michelle that there appears to be majority support for this within the Australian population. But will it hold up once there is campaigning and once there are questions are asked and what some of these elements do come out and, and campaign and raise questions or concerns, some of which may not necessarily be justified, and I'm referring here specifically to this idea that an advisory body, as proposed, would constitute a ‘so called’, third chamber of Parliament, which is not consistent with what the Uluru statement is putting forward in the form of a Voice to Parliament and an advisory body, not a third chamber.

Sunanda Creagh: One of the questions here says, the right to march and protest is under threat. Is this an abuse of power and privilege? Or is it just about maintaining order?

I have seen this discussion happening in the news. Is that something that you guys have followed?

Tim Soutphommasane: Not in…

Sunanda Creagh: What do you think is this not the state of play in Australia in terms of our…

Tim Soutphommasane: … close detail, but I would say this, you know, the COVID experience, in my view, did see a very fundamental challenge to our culture of human rights and civil freedoms. And I for one, was alarmed at how ready the majority of Australians appeared to be, to not question, executive power being expanded in dramatic ways during the period of COVID. Now, that's not to say that restrictions may not have ultimately been justified for periods of time. Or, what alarmed me, was that, there did seem to be this instinctive response to questioning, about government powers and responses, which indicated that human rights, or civil rights, was something secondary. I mean, consider what Dan Andrews, for example, said when he was questioned about some of the actions that he took, as Victorian Premier. And to paraphrase, at one press conference, in an exchange that he had with journalists, I believe he said something along the lines of I'm not interested in human rights. And this is the Premier of a state that has a Charter of Human Rights, which, which I think was quite notable. What was just as notable was how few people seemed to get exercised by this at the time. And looking back, my view would be that anyone talking about freedom, or civil liberties may have been quickly painted as an anti-vaxxer, or culture warrior, who wanted to let COVID be let rip, who didn't care for the loss of life or for illness. And I'm not sure that was quite true. You know, obviously, there were elements that were ugly, in protests around COVID. But I think there was also a debate to be had about the limits of government power, and whether liberties and freedoms were restricted for longer than they needed to be.

And bear in mind, the restrictions we lived under, for periods during COVID, where you couldn't leave your house without a legitimate reason, or you only had an hour to exercise, public health orders coming up at the rate of one every few days or one every week. You know, think about the culture we had in 2020, where you really needed to be on top of your public health orders in case you were stopped by a policeman when you were out shopping, you know, did you have a legitimate excuse to be out? Were you in a designated area of concern, or whatever the language might have been? And think about how we were here in Sydney, for example, living in two different cities, where 12 local government areas were subjected to particularly harsh restrictions. And I'm not sure we had the kind of public scrutiny or debate of those interventions that I would have expected from a country that is committed to human rights or civil liberties, you know, may not be a popular view. But I dare say that these were debates we didn't have, because people were very content to say that anyone who, who was referring to freedom was a bit of a nutter, and wasn't sensible around COVID. And that's something of concern for me.

Sunanda Creagh: Mmm, okay. The discussion around that COVID lock down period reminds me, Michelle, of a brilliant conversation essay you wrote at the time about returning to Kath and Kim, during lockdown, and finding comfort in that place again. And then, there's been some, there's a bit of a part two to that story isn't there? Something happened recently with Kath and Kim?

Michelle Arrow: Yes. So I… during Kath and Kim, which was first aired on Australian television in 2002, so, 20 years ago, this year. I introduced it to my 12 year old daughter last year during lockdown, because we were, you know, looking for fun things to watch. And I thought she would enjoy it. And of course, she's become completely obsessed with it and can quote large bits of it back to me, you know, at length. And so when I was I was thinking about contributing to that series about writing about, you know, what we were watching in lockdown. I was thinking about it as a historian, what does it mean, this show is 20 years old. You know, it emerged in the, sort of, wake of 911, and a time when Australians were generally kind of retreating to their homes and focusing on their backyards and renovations and reality TV and all of these things. So, kind of, the essay was great fun to kind of reflect on that. And then of course, one of the things that came out of writing that essay was that they read it, Kath and Kim, the creators of Kath and Kim, read the essay, really liked it. And so the anniversary special, I don't know if any of you have noticed, it's coming up this weekend, on Channel Seven. And so they asked me if I would kind of contribute to that in the capacity as, kind of, historian. So I'm Kath and Kim's historian on this show, apparently. I reckon I'll be like, two seconds worth, you know, on the show, but it was just one of those lovely things, of, where, the conversation can take you. You know, like writing this little piece that was really, you know, a lot about comforting myself and my daughter and thinking about what what it meant to be in lockdown and kind of using the screens, you know, that we watch at home as a sort of window into the outside world when things felt a bit uncertain. It was a lovely little, sort of second act for this little piece that I wrote.

Sunanda Creagh: So your vast body of scholarly work on everything to do with gender, politics, history. The thing you'll be remembered for is Professor Kath and Kim.

Michelle Arrow: Professor Kath and Kim. Yeah, yeah.

Sunanda Creagh: Brilliant.

Michelle Arrow: Look, there are worse things to be remembered for. That's totally fine.

Sunanda Creagh: Tim, there's a question here, referring to an Australian being held prisoner in London, and, as a political prisoner in London, which I think is a reference to Julian Assange. We haven't heard a lot from this government about that issue. I wonder if, do you think we will? Or do you think that there's, you know, he's somebody who was doing journalistic work, I know that the journalist union, which I'm part of, has been advocating for his release. Do we think that there is progress that could be made there? Or is that a closed chapter?

Tim Soutphommasane: I'm not privy to what the government is thinking about here. But looking at the broader public sentiment, I am detecting a bit of a shift, perhaps, in sentiment. I think there appears to be some growing public sympathy for Julian Assange. And it wouldn't surprise me if the issue returned to the political debate in a more noticeable way.

Sunanda Creagh: Michelle, I know that earlier, I think, was earlier this year, you were doing something about the anniversary of the Whitlam election, which I think is coming up in early December is that right?

Michelle Arrow: That's right. Yeah. Second of December is the 50th anniversary of the election for Whitlam government.

Sunanda Creagh: What are your reflections on that period? And where we are now and how things compare?

Michelle Arrow: Yeah, so I've edited a book of essays about women and Whitlam, which will be released early next year. And so I've been thinking very much about this. And so, you know, writing about Grace Tame, and Brittany Higgins and the whole issue of women and politics in Australia, and kind of reflecting back on what was happening 50 years ago. Because I think one of the things… and it's again, it sort of speaks to this point about – government's agendas are not always shaped by what governments want to do. Sometimes government agendas are shaped by what citizens get together and decide to do. And I think one of the things that we can take away from 1972 is that women kind of barged their way onto the political agenda of the Whitlam government. Whitlam had a number of issues in his policy platform that, of course, were of direct importance to women, promises around health care around education, around schools funding. But it was the women's electoral lobby, who organised in early 1972, and said, we're going to do a candidate survey. So we're going to interview every candidate running for office in Australia and ask them 30 questions on issues that are relevant to women. And that changed that election, because that meant that those issues suddenly became part of political debate, the government had to respond to those issues. And then, of course, the government found that they had, you know, there was an emergence of a new constituency of voters out of that election, that then shaped a lot of the decisions that they made over the next few years.

So I think one of the things that has been heartening, I suppose, about that, is thinking about, that we still, I think, do have some power to shape the political agenda in that way. And, that, you know, we can see in the phenomenon of the teal candidates, people who had never volunteered to help a political candidate before were suddenly becoming part of political debate and discourse and door knocking, and making volunteer calls and all of those things and, and that, to me, I think, was a really positive sign that governments are shaped, in part, by the things that citizens bring to them and the ways that, you know, we can kind of shape that agenda. So I think 50 years on, it's important to reflect about those issues, as well as reflecting on the broader legacy. You know, it's interesting that we have a Labour Government 50 years later, but we haven't had a lot of Labour governments, you know, in Australia, and there haven't been a lot in the last few years. So it's interesting to think about what the legacy means to the Labour Party, as well as what it means to the nation. I mean, three short years, you know, in terms of the spate of reforms that Whitlam enacted, like, I think it's a reminder that governments should and can be ambitious, as well as meeting their promises, you know, and it's, I think, it's up to us, partly, to hold them to demand ambition from our politicians.

Sunanda Creagh: You use that phrase, it's up to us. And there is a question here that says, “Reckoning with power and privilege is about more than just party politics. It's about recognizing one's privilege and using your own sphere of influence to create a positive change. Can we talk about individuals, dot dot dot. Or universities question mark, exclamation mark.” But you know, we're not just talking about abstract figures in the government that each of us does have individual power to some extent to create change. So how do we recognize one's own privilege and use our own influence to create positive change?

Tim Soutphommasane: Whoa, I think it's a question about citizenship. You know, what does it mean to be a citizen? We often don't think about such questions because citizenship for many of us, many of you, might well be a birthright, something you're born with. But think about, again, I'm going to turn back to COVID, and the experience of COVID. One of the striking features of COVID was just how little the value of citizenship had for many of our fellow Australians. After all, many Australians, 10s of 1000s citizens, were unable to return home to Australia because we had shut the borders. This is not just shutting the borders to those who are not citizens or residents of Australia, this is in relation to Australian citizens seeking to come back. That to me has not really been reflected upon, to the degree I would have expected.

If we're talking about a ‘reckoning’ in 2022. More broadly, citizenship, of course, isn't just about your passport and your ability to move in and out of the country. It's about your place in the political community, having your voice heard, being part of the decision making processes of the country. A question for me listening to Michelle, is whether this surge of civic energy from the election this year with all of these people volunteering and being active in politics, for the first time, is whether this will be sustained in the years to come, or whether this will be a one off? Will all of these people being part of politics for the first time feel energised about this? Or will they feel disappointed, or disillusioned? You know, after all, one shouldn't be engaging in politics expecting edification all of the time, more often than not, the reality of politics and the reality of citizenship is that you will be disappointed. But that makes your achievements all the more sweeter if you're talking about achieving change or progress. And then I think this year, you know, you think of some of the figures that we've referred to already, and people like Britney Higgins and Grace Tame, these are examples, I think, of people who have been able to use their voice, and who have been able to shift debates and to change public understanding of the issues. You think of newly announced New South Wales Australian of the Year, Craig Foster. Another example of someone who has gone out in public debate and advocated for things in the realm of immigration, anti-racism, among other things. These are all examples of citizens who have spoken up and had an effect on our society. So I would hope that in reflecting on all of this, we can think about the change we can create. We don't always get the change we want, we can sometimes be disappointed. But you've got to be prepared to have a fight for what you believe in, if you are going to be thinking about change.

Sunanda Creagh: Well, I just wanted to touch on the death of the Queen this year. There is a question, which is now we have King Charles, is this going to reinvigorate the debate around the republic in Australia? I think the government has signalled they're pretty focused on, let's work on the Voice to Parliament referendum first, and we'll worry about the other stuff second. But do you think that there is an appetite in Australia for having that debate again? Or are people quite happy with what we've got? We voted on that, and we're staying where we were.

Michelle Arrow: Yeah, that's a good question. Look, I think it's interesting that it kind of hasn't really been on the boil as a big issue, I suppose. But it is interesting that the new government appointed a minister for the Republic. So there's clearly a sense of a sequence that we will do the Voice to Parliament first. And I think the optimistic idea is if, in a second term, there might be a vote on a Republic. It was always kind of one of those issues that was pushed off until after the Queen died. And I think the fact that it sort of feels like it happened very quickly, even though she'd been on the throne for a very long time. I think that that happened awfully quickly. And I don't get the sense there's a sort of strong wellspring of affection for King Charles, in the way that there was for the Queen. I think they're quite different political, public figures, you know, we sort of know more about Charles, perhaps, than we do about the Queen. And that may not necessarily be to his favour. I mean, I still remember the 19, living through the 1990s kind of tabloid scandals around Charles and Diana. And I do think that does have a different effect, a different colour, to his role as monarch. But then on the other hand, you know, the kind of advocacy around climate change and things like that. So I'm not quite sure whether, I just get the feeling there's not a great deal of enthusiasm for him. But I'm not sure that there's enthusiasm for a Republic in the way that there was, I think back in the late 1990s. I just, I don't know if the ground’s been prepared for that yet.

Tim Soutphommasane: Yeah, I agree. I don't detect the urgency of this yet. Although it does appear that there is still significant, if not, majority support for Australia to become a Republic, and it just isn't there with urgency. I mean, it's, you know, do you feel a sense of urgency around a piece of civic renewal involving how we think about the Head of State? I mean, that's not the language I think you use to drive political change, and this is the challenge for Australian Republicans. Is there a language that you can use to corral support for constitutional change? Because again, instinctively, there would be a conservative mindset, I would say, to Australian society around institutions and civic and political architecture. And even if people may sympathise with the idea of having an Australian as Head of State, or whether that translates to political will, and energy to agitate for a public is different. So I agree with Michelle, that when you had the debate in the 1990s, this was, and the referendum in 1999, this was the product and culmination of close to 10 years of public debate with Paul Keating, in particular, making this part of a national story and a big picture about renewing Australian identity, linking it in with reconciliation with Aboriginal people and linking it in with Australia's engagement with Asia that was part of a clear passage…

Michelle Arrow: A big narrative, part of a bigger narrative. Yeah.

Tim Soutphommasane: …So the question would be, well, if that's what's needed to take constitutional reform, into political debate and into widespread public consciousness, what's the package for the Republic today? And that remains to be seen yet. Isn't to say that there isn't a story that could be crafted and told, but the tilling of the soil has not taken place yet.

Sunanda Creagh: This, I think, might be my final question. We're coming close to the end. But, we've talked a little bit tonight about some of those economic pressures, you know, interest rates, cost of living, wages stagnating, it occurs to me that the impacts of those problems are not evenly distributed in our society. I wonder if you could just reflect on, you know, what the ways in which those impacts are unevenly distributed? You know, your work is particularly around women, you know, in a world where those, you know, economic pressures are there. What are some of the impacts?

Michelle Arrow: Yeah, I mean, one of the things that I think was most kind of devastating, really about reflecting on the early days of the pandemic, back in 2020, was when the COVID supplement was introduced for people on job seeker parenting payments. And ACOS did a really amazing report where they interviewed a lot of people who talked about the impact of that extra money, and, you know, single mums talking about, I could buy my children, new shoes, and, and a winter coat, you know, and things like that. Like, it was quite appalling, the kind of ways that we still, I think, haven't really grappled with the lives of people on those very low incomes, who rely on government support, in order to live and that the way that those payments are very low. And of course, we're now seeing a kind of rising homelessness and rental crisis around people on, not even just people on very low incomes. But I think people on very low incomes are, of course, the most acutely affected by that, you know, and we're going to see, you know, an increase in homelessness, because of those rental crises. And they're complicated, they've had a very, we've almost had sort of 20 or 30 years of policy settings that have created these problems. But of course, they're now coming home to roost, quite spectacularly with this increase in inflation. And, you know, the kind of inability, I think, to really grapple with disadvantage, we've been so focused, I think, on the role of the policy settings that can help people buy an investment property, and not necessarily thinking about the people that need, you know, people who, for many reasons, no fault of their own, are relying on government payments for, you know, basic needs, and haven't really been able to get them. So I really, I'm very concerned about what the future looks like for those people, as well as all those people who bought homes in the last couple of years and are now going to have to deal with, you know, rapidly increasing interest rates. And there's already research that suggests that there's a lot of not just rental stress, but mortgage stress. And that's, that's increasing, too. So it's a huge political problem, I think, potentially, for this government. They're going to need to grapple with that really quickly.

Sunanda Creagh: As we head into a potential recession? I don't know? Tim?

Tim Soutphommasane: Oh, it's, you know, it's a mug's game to predict what's going to happen, but it's very, it's possible, you know, I think the clouds are gathering and what we're seeing is, is how economic reality is exposing some aspects of our society which may have been conveniently concealed by close to three decades of economic growth. And by statistics of low unemployment. I mean, if you were to look at the overall picture of the Australian economy today and look at, you know, we're still in positive territory and economic growth, unemployment is very low by historical standards, but that does mask a lot of precarious living that people are experiencing, you know, the the technical definition of unemployment is that you actively seeking work and haven't worked to one hour for the past month, I believe, someone may well correct me on the formal definition of unemployment.

Sunanda Creagh: But there's a lot of people who fall through the cracks of that definition.

Tim Soutphommasane: So, the unemployment rate that we see, that's constantly referred to as a marker of the state of the economy, does mask a lot of underemployment, and doesn't tell us much about the casualisation of work either. All of these things, we may well have been able to have some level of indifference to, I'm not saying it was right, because the economy was chugging along. But when the economy isn't doing so well, it becomes harder to continue as though things are normal. So we will see a test of our safety net in Australian society in the coming years. And how we respond to it will reflect our values as a society to some degree. I mean, we're seeing here, a challenge to the kind of society we want to be. The federal government right now is in an unenviable position, where it has a very difficult economic situation that it has to navigate its way through. And if we think of history, you know, we've talked about the Whitlam government, that was, you know, a reforming government that had to confront the brutal reality of stagflation. And if you think of the long sweep of history and where things are at right now, there are some big questions that Anthony Albanese and his cabinet will need to answer very soon. We've reset for now, but the hard work for them begins.

Sunanda Creagh: On that cheery note, we might draw it to a close. Thank you very much for joining us tonight at 2022: Reckoning with Power and Privilege. I just wanted to thank our panel for a fantastic discussion. And taking part in this conversation. Let's give them a round of applause.

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. For more information, visit centerforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

-

1/3

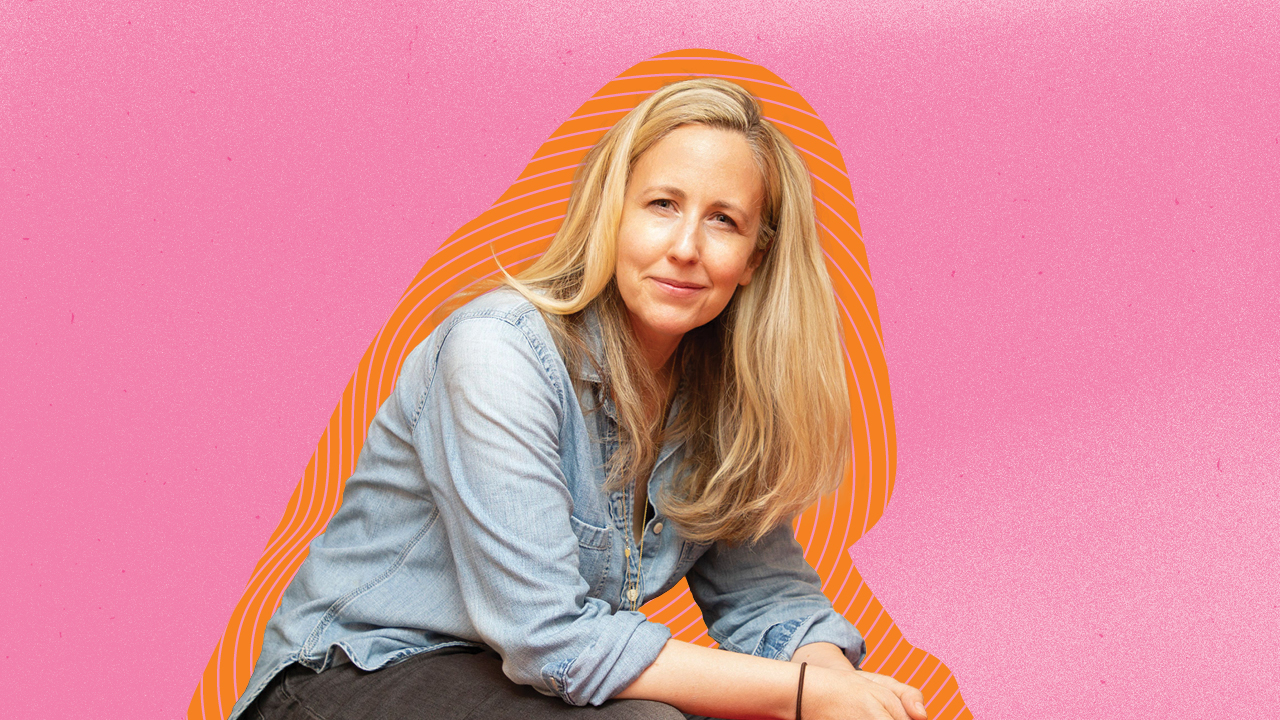

Michelle Arrow

-

2/3

Sununda Creagh, Tim Soutphommasane, and Michelle Arrow

-

3/3

Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane is a Professor of Practice (Sociology and Political Theory) and Director of Culture Strategy at the University of Sydney. A political theorist and human rights advocate, from 2013 to 2018 Tim was Australia’s Race Discrimination Commissioner. His thinking on patriotism, multiculturalism and national identity has been influential in debates in Australia and Britain. He is the author of five books, most recently On Hate, and has been a columnist for The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and the Weekend Australian.

Read Tim Soutphommasane’s article, ‘We’re about to have Australia’s most diverse parliament yet – but there’s still a long way to go’, here.

Photo credit: Michael Amendolia

Michelle Arrow

Michelle Arrow is a Professor in Modern History at Macquarie University and a fellow of the Whitlam Institute. She is the author of three books, including The Seventies: The Personal, the Political and the Making of Modern Australia, which was awarded the 2020 Ernest Scott Prize for history.

Read Michelle Arrow’s article, ‘Making change, making history, making noise: Brittany Higgins and Grace Tame at the National Press Club’, here.

Sunanda Creagh (Chairperson)

Sunanda Creagh is an award-winning journalist and a Senior Editor at The Conversation. Previously, Sunanda has been The Conversation's FactCheck Editor, News Editor and Arts + Culture Deputy Editor. She began her career at The Sydney Morning Herald and worked at the Reuters bureau in Jakarta as a political correspondent before joining The Conversation in 2011.