Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida: How Many More Women?

It’s important for one woman to speak because it encourages more women to come forward.

The right to free speech is also a part of your self-fulfilment and being able to speak about what you believe in, being able to speak about your experiences and the truth – we want judges to recognise that in defamation cases.

In the wake of #MeToo, women are increasingly speaking up against gender-based violence. But as they have grown empowered to speak, a new form of systematic silencing has become more evident: the spike in survivors speaking out has been followed by a spike in legal actions against them and the media.

How many more women: have to be raped or abused before we act? need to accuse him before we believe her? will be failed by the criminal justice system? need to say something before we do something? will be sued for defamation for speaking out? will be contracted to silence?

In How Many More Women? Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida examine the laws around the world that silence women, and explore the changes we need to make to ensure that women's freedoms are no longer threatened by the legal system that is supposed to protect them.

Hear Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida live in-conversation with Jane Caro for a powerful and accessible exploration of our legal systems as they break open the big judgments, developments and trends that have and continue to silence and disadvantage women.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas, UNSW Law & Justice and Sydney Writers' Festival, and supported by Allen & Unwin.

Transcript

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Welcome to the UNSW Center for Ideas podcast. A place to hear ideas from the world's leading thinkers and UNSW Sydney's brightest minds. The conversation you are about to hear features human rights lawyers, Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida, and is chaired by author Jane Caro, as they discuss the legal response to Me Too in Australia and around the world. We hope you enjoy.

Jane Caro: Well, hello, here we all are, speaking up! Let's hope we don't get sued. Becoming an occupational hazard of being a woman with a mouth, or so I felt when I read this book. And given that I've got a particularly loud mouth, I took lots of notes. Thank you, Justine, for that terrific introduction and summary of where we're at now. I was pretty horrified to hear we’re 143rd out of 146 on the Equality Index…yay! I also, of course, need to welcome Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida, it's so wonderful to see them both here. I have thoroughly enjoyed reading this book, and also been extremely disturbed by it. Now it says in front of me here, in my speaking notes that my name is Jane Caro and I'm, and then it says, insert own words about who you are. So I'm just gonna say my name is Jane Caro. I'm a feminist, and I speak up… and that’ll do it. But I'm not a lawyer. So I'm not going to be approaching this conversation from a legal expertise… perspective.

Before we get into that conversation, I would also like to acknowledge the Bidjigal people who are the traditional custodians of this land. And I would like to pay my respects to their elders, both past and present, and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are here with us today. And can I please also encourage you all, if you haven't already, to read the statement from the heart. Not only is it an important document, but it's actually a beautiful piece of writing. And there's not a lot of beautiful pieces of writing in the Australian Constitution. So it's good, somebody's done some, and for such an important and heartfelt reason, which is probably why it's so good.

Jennifer Robinson, who's sitting next to me is an Australian Human Rights media lawyer and feminist, who is internationally recognized for her work. She represented Amber Heard in relation to Johnny Depp's 2020 defamation case in the UK. We're going to hear a bit more about that, I think, because it features very heavily in the book and was one of the parts of the book that really, I don't often read a lot of books when my heart starts to thump, but I got quite agitated. So hopefully, you'll all get quite agitated too. She's also defended Julian Assange and advised WikiLeaks since 2010. She's a practicing barrister at Doughty Street Chambers in London and has acted in key human rights, freedom of speech and information cases before the British courts international and regional courts and UN special mechanisms. She's an ex-student from Bomaderry High School, and like me, an ex-student of Forest High, an absolutely stalwart supporter of public education in Australia. And that was not in the notes.

Next to Jennifer is Keina Yoshida, her co author and, Dr. Keina Yoshida is a human rights lawyer, media lawyer and feminist. She's a lawyer with the Center for Reproductive Rights and was a practicing human rights barrister at Doughty Street Chambers, where they are currently an associate tenant. Keina has acted in key human rights cases including on LGBTQIA rights and women's rights. Keina is a visiting fellow at the Center for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics. So we are sitting with two extremely impressive and highly qualified women.

I'm gonna ask you a fairly obvious question to start with, but it was one that really popped into my head as I was reading your book. We're in what they call the post ‘#metoo’ era, and as Justine pointed out, you know, there was a worldwide outpouring of women's stories of abuse and harassment. And there was also a huge rise in defamation cases, to those of us who naively perhaps celebrated the smashing of the giant female silence, which after all, this lasted for thousands of years, probably, and some of the most poignant stories in that tsunami of revelations, back in 2017, that I read, were of women in their 80s, who talked about experiences that they had never spoken of in their lives. And I thought that was just extraordinary. So some of us celebrated the smashing of that silence. And I expected anyway, a rise in prosecutions for rape and sexual assault. So why on earth? Did the opposite happen? Why did we get this spike in defamation cases? Not what we all thought would occur, which is, abusers being brought to account. Keina, what do you reckon?

Keina Yoshida: Okay, I think, first off what you had in 2017, is the viral hashtag Me Too. But it's important to recognize that Me Too started far before that, with Tarana Burke, starting the campaign in the US. And so that's the first thing. And the second thing is, I think you did get a rise in reporting, of sexual assault, sexual harassment and different types of claims. And then it's really quite obvious, because if you want to shut that speech down, well, then you can turn to law. And I think the law has always been complicit in being a tool for the most powerful. And what you've seen is defamation claims and other types of civil actions being used to silence women and other survivors of violence.

Jane Caro: You agree, Jennifer?

Jennifer Robinson: Well, obviously we agree, we write in a joint voice.

Keina Yoshida: Well, that’s true.

Jennifer Robinson: I absolutely agree with Keina. So, one of the reasons why we decided to write this book and write it together is because we were seeing this in our own practices. So we were being asked to advise, not just journalists, though we write in the book about our experience working in house with media organizations, and newspapers trying to get these stories through the newspaper. And so I hope what you get from one of the chapters in the book is actually, you'll never read another story, a Me Too story in the newspaper in the same way, because you'll see the obstacles that journalists have to jump through in order to get this to print. So it's not just getting the stories in the paper, but the number of defamation actions and the defamation risk. So we've been advising not just journalists and media organizations, but frontline services, rape crisis centers, women who have spoken out about their abuse, family members who have spoken in support of women who have come out about their abuse, their friends and family members who have spoken out or tweeted about them in in support. So because we were so frustrated by what we were seeing, and so much of what we see also doesn't get into the public domain, because a lot of this stuff actually settles because people can't afford to defend their right to free speech, the threat of litigation is enough to make someone be silent. And when you get a threat letter, it's confidential. And if you decide to self censor, which many people do, it never reaches the public domain. So what we write about in this book is the tip of the iceberg.

Jane Caro: Yes, I've often thought that the reality of power is not that the powerful person actually has to do anything. They merely have to have people around them who know what they might do, which is enough to actually send that chill right across. Do you think that's actually happening now? Is that chill occurring? Are women shutting down and shutting up going back into the old silence?

Jennifer Robinson: Well, I mean, I can only just speak to my own experience after the Depp case in the United States. And I think, the vitriol and the global shaming and ridicule of Amber online. I can speak to anecdotal experience from my colleagues who have been sending me messages saying how, particularly women working with domestic violence victims, how many of their clients are deciding not to take their cases, not to sue their perpetrator, being threatened by their perpetrator, saying don't be an Amber, if you speak out, no one will believe you. You know, Amber's name has become synonymous with that now, and so I absolutely believe that the impact of that case is, and I'm hearing from my colleagues that it is having an impact. And not just in the UK where we work. I'm getting reports from lawyers in India and Pakistan. That's the depth and the global nature of the reporting on that case. And so just imagine, and I say this all the time, but if you're a woman, and one in three women have suffered sexual violence or gender based violence, if you've heard your family members, your friends, your colleagues, ridicule Amber, through the course of what they saw on social media, and make comments like that, why would they ever come forward with her own story of abuse? If they see your attitude towards that case.

Jane Caro: It almost felt deliberate to me, and I do remember, I'm not going to mention any names, because having read your book, I'm now too terrified. But it was a high profile case, and one of the people involved in it said to me, privately, I don't understand why they're going so hard against her. They're even going for costs. And I said, oh, I think I know why they are, it's an example, so that no other woman, who might be in a similar situation will speak up, because they know that there will be no end to what they will pursue her for. So it feels like a deliberate strategy. Would you think that that's true?

Keina Yoshida: Yes. I mean, it's a weaponisation of the law. And the UN Special Rapporteur on free speech has said that. She has said, it is a form of gendered censorship. And I think at the same time, though, one of the great things about writing this book was that we were speaking to women and journalists and people who have been facing… two women in particular, who I mean, we interviewed one woman who said, yes, I've faced a defamation suit, but actually, you've got to speak to this other woman because she's got it way worse. So then we go to speak to her, Catalina Ruiz-Navarro, she's incredible, you can follow her on Twitter, catalinapordios, is her Twitter hashtag, and her and her friend started a small feminist online magazine together, Volcánicas, and they published some allegations about a very powerful, I won't say the name, film maker in Latin America. And he launched, we think, at least five lawsuits against them. And in Colombia, it's both criminal defamation and civil defamation. And it goes to a court and a judge says, well, actually, maybe there's an issue with fair and accurate reporting. So you need to have a correction, you need to provide more information. And so they went away. And they said, okay, it's not just allegations, it's 14, we're publishing. Here are the other ones that we didn't include in the first report. And you just think, wow, you know, and there's other examples in the book, where you see women being sued, these deliberate actions being taken against them, and them saying, no, wait, I'm also going to use the Master's tools to fight back.

Jane Caro: Yeah, you give a lot of examples of that, which is wonderful, because it gives you hope. But I want to, for a minute, look at kind of the other side of this, because one of the things that happened for me, following the social media stuff about Amber Heard was the number of women who were involved in that social media, really, crucifixion, of Amber Heard. Including women that I know, and like and admire, and who would say, absolutely they were feminists. Who were tweeting things like, oh, she's not being abused. She's the abuser. Which is the DARVO where the perpetrator manages to deflect, what does DARVO stand for, again? Deflect…

Keina Yoshida: And attack…

Jane Caro: Attack, reverse, victim and offender. And that's, basically it was a classic example of that. I know your lawyers, not psychiatrists, and psychologists or sociologists, but you must have thought about it. Why? Why did so many women get involved in this? Horrible evisceration of a woman?

Jennifer Robinson: I mean, internalised patriarchy is a thing.

Jane Caro: Mmmhmm!

Jennifer Robinson: But it's hard to talk about it and people get, you know, when you say it, people sort of feel patronised, but you know, we live in a patriarchal society and a culture where these male centric myths and stereotypes and tropes about gender based violence are pervasive. I mean, in the course of the book, and that's why we start with the history of the law and some statistics around the way the law has regulated gender based violence and the way that society perceives it, is because these myths are so pervasive, within society, within the police, within judges, among lawyers. That's why they run these kinds of arguments in court, and that's why they work in front of juries. And so I think we have a big cultural issue and a big education piece to be doing around gender based violence in society. And I think we really need to examine our views. So for example, the immunity for rape within marriage was removed from the law in this country in 1994. That was the last state to change the law. So that was, you know, marriage was an irrevocable contract for sex, you could be if you beat your wife up and raped her, you could be prosecuted for assault, but not for rape. That was so recent. But recent studies, both in the UK and Australia show that most men, and some women, still perceive that it is your obligation and a man's right to have sex with you, if you're in a relationship.

Jane Caro: Yes, he's bought you body and soul, in return for a home. You have to come across.

Jennifer Robinson: But I mean, I think that we are all affected by these myths and tropes, which are so pervasive in our society. And unfortunately, we're perpetuated through that awful online social media campaign, to the point where it was horrific. I had friends calling me saying my kids are on TikTok, and they're saying she's a liar and she deserved it, and you know, she was, you know, she was awful, she was bad, you know, there was all this… it was really devastating actually.

Jane Caro: I felt the same way, I mean, I wasn't nearly as closely involved, as you were, but it felt almost medieval, as if she had been placed in a kind of global stocks, and everyone was throwing rotten vegetables at her. And the extraordinary thing, and I think perhaps, and I don't know, I'd forgotten this, even though I thought I'd followed it quite closely until I read the book again, is that Amber Heard hadn't done hadn't started this, she didn't actually take on Johnny Depp. She wrote an article where she didn't mention him or say anything about him specifically. And yet, he was still able to drag her through two lots of court cases, and eventually, after shopping around for a jurisdiction, win. I mean, I must be very naive, because I was utterly shocked by this, that this can still happen. And yet you point out in the book that this kind of thing happens all over the world. Tell us about a few, I mean, you've spoken about the Colombian situation, which actually seems rather enlightened in comparison to most of the others. But there is the Japanese lady who has stood up against, again, a powerful man, and of course, here, Eryn-Jean Norvill, who was dragged, unwilling, into a court case and saw herself and her reputation utterly trashed. So even if women don't actually do anything, don't actually name anyone publicly, the law can beat them into a pulp. How does this… how is this allowed?

Keina Yoshida: Yeah, I mean, Shiori’s case, I think, is one of those cases when we first started thinking about writing this book together, and we were working on these cases, that really just came to mind. I met Shiori many years ago, and she's been described as the leading light of the Me Too movement in Japan. And she was a young journalist. She went out for dinner with a very senior broadcaster. And then the facts after that are disputed, but she says that she was raped by this man in a hotel room when she was unconscious. And he says that the sex was consensual. She goes to the police about five days later, and then what happens is absolutely horrific. The other night in Melbourne, I think Clem Ford said, you know, give a trigger warning and this is real trigger warning territory where when she reports it to the police, she asked for a female police officer. She's not given one, instead, she is told to go into a room with a group of male police officers, given a life sized stall until to act out what happened, while they film it. Now, after that, the police decide not to investigate further or press charges. And what choice then, does Shiori have? She decides to hold a press conference and say, I want this to be investigated. And it's on the basis of that, on that public interest statement that she makes, that he sues her in defamation. And similar to Amber she gets absolutely horrific trolling. And when I met her in London, she was effectively exiled, the trolling had got so bad. And I think, you know, we are seeing this around the world. We spoke to lawyers from South Africa, from Kenya, from Uganda, and Shiori said, you know, different legal system, same story. And that is, I think what we are trying to achieve in the book, like, women are being silenced all over the world. The legal answer to your question, Jane would be, the problem is in defamation law, that the person just has to be identifiable to people who they know. And that is a part of the problem in Amber's case, and in many cases.

Jennifer Robinson: Yeah, so I think what people don't understand is in Amber… Amber didn't give any interviews to the media. So she signed an NDA, after she got… she went to court, got a restraining order signed, an NDA, didn't speak about the details of the violence ever again, didn't want to. And it was only post Me Too, when people started asking more questions about Johnny Depp being cast in films, that op-eds were written in the newspapers, and it was an op-ed in The Sun, where he was described as a wife beater, that he sued The Sun. And she was put in the same invidious position that Eryn-Jean Norville was whereby, well, even, I mean, arguably, her situation was worse because the details weren't public. But when the newspapers sued after publishing an accusation based on her personal experience, you have no agency over the proceedings. So the newspaper is the defendant, he's the claimant. He's suing saying that you lied, the only agency you have is to give a witness statement to help the newspaper prove your truth. And so Amber took that decision. In the US, it was different. She wrote an op-ed about advocating for Congress to improve protections for survivors, precisely because of what she had experienced after getting that restraining order. And she speaks in the article about being a survivor. Didn't mention him, didn't talk about what happened, just said, stated a fact. She became a public figure associated with domestic violence, ‘and this is what happened to me’. And that was enough for her to be sued for $50 million, and lose the case and be ordered to pay over $10 million.

Jane Caro: So that means…

Jennifer Robinson: Even though we had won the case in the United Kingdom. And I really recommend you go and read that judgment, it's over 100 pages long, a meticulous review of the evidence that I spent two years working on with Amber, outlying his evidence, her evidence, the text messages, the medical evidence, the corroborative evidence, and to me, it is absurd, in my opinion, that a jury could come to another outcome.

Jane Caro: Well, basically, what you're saying there is that any woman who was married to someone who abused them, can never say, publicly, I'm a survivor of a marriage where I… because he could claim, well, that identifies me, therefore you have defamed me.

Jennifer Robinson: Well, one of the people we interviewed for the book, and I want to acknowledge her if she's here, Chanel Contos, so I hope she's here somewhere. She's supposed to be here. So congratulations to Chanel, on her brilliant work. But what was really interesting is speaking to her… so with her teachers consent, was asking people to share their stories, anonymously, of their experience of sexual assault in schools, and was posting their stories anonymously online. Chanel was getting defamation threats. And because it doesn't, it doesn't… what people need to understand, as Keina explained, it doesn't matter if you don't name the person that you say did it to you, as long as they're identifiable. So if you say I was raped by my boyfriend when I was 16, then people will be able to identify who he is. There'll be people who know you, people who know him will go, I know who she was dating when she was 16. That's so and so. So when Chanel was posting these stories on the website, she was getting threats. And the threats were because… literal legal threats, from men who said, I am identifiable from that information, from the story that was told, I was the same year that it named someone, at this year at this boy's school, I was that person, I fit that description, you need to take this down. And so that's how difficult it is. So I think there's a perception that if you don't name the person, then you're fine. Actually you’re not. Or potentially not.

Jane Caro: I mean, the therapist once said to me, you are only as sick as your biggest secret. And that really, has always stayed with me as an extremely wise thing to say. But what we're now doing is saying to women, really, you keep it a secret. So how does this silencing affect women's ability to move on, from what is an appalling, traumatic experience, and actually heal if they are literally forbidden and in some of them, we're gonna get to NDAs in a minute, but in some of the NDAs, they're literally for bidding from telling anyone, including a therapist, or their most beloved…

Jennifer Robinson: People.

Jane Caro: People, about what’s happened to them. What does that do?

Keina Yoshida: Yeah, I think we look at some of the judgments that exist around the core on this issue. And there's a really interesting case in the UK, which was about a, an incumbent MP, who was fined on the balance of probabilities by a judge to have been raping his wife. And he wanted that judgement to be kept a secret. And she argued, along with some women's rights organisations, that effectively that would silence her forever. And the judge had already found, on that balance of probabilities, that he had been carrying out coercive control, and that that silencing through the judicial system was would be a continuation of a form of coercive control. And I think some cases that have recognised this importance of the right to be able to tell your truth. And then not only that, right to tell your truth, but for other people to be able to listen to that. And I think it's a really important point that the right to free speech is also a part of your self fulfilment, being able to speak about what you believe in, being able to speak about your experiences and the truth, and we want judges to recognise that in defamation cases, both those cases that we talk about in the book are not defamation cases. They are, I mean, one's an injunction type case, and the other one is a family law case, you can read about it. But you know, we need defamation courts to recognize that this is a part of the healing process. And that this is free speech.

Jane Caro: Yeah. Yeah. And you point out that it's a ,sort of, it is actually about his right to reputation and privacy, versus her right, to literally free speech. To be able to speak about her own life and her own experiences. And how, after all, do you help other women avoid finding themselves in similar situations? If you're never allowed to speak about what happened? I mean, you talk about the Harvey Weinstein case, which is very much about literal use of money and power with NDAs and spy agencies. I mean, if he wasn't a Hollywood producer, he should be, because it's very overly dramatic, but incredibly effective. This inability of the women who all knew what Harvey was… to have to actually be able to warn young, naive, starstruck, ambitious women coming to work for that organisation. Surely, it puts all women at greater risk?

Jennifer Robinson: Well, I mean, that's what we talk a lot about, silos of silence, about how the law keeps women in silos of silence. And one of the key points we wrote in the book, is that we can't, as a society grapple with the problem of violence against women, if we can't talk about it. If we don't know that it's happened, we don't know the extent of it, women can't talk about it, then we can't even begin to deal with it. And that's the starting point that we come from in talking about the public interest, and women being able to speak out about it. Because if we are kept in silos of silence, then we don't we don't know whether there's a repeat perpetrator. We don't know the extent of the problem. We don't know how much resources as a government we need to be putting into addressing this problem. And so, being able to talk about it is incredibly important. Weinstein was really using contract, to keep women in silos of silence. And so when we're talking about non-disclosure agreements… and non-disclosure agreements are prolific. And, I mean, it is a contractual term, but they're in all kinds of contracts. So divorce agreements, settlement agreements, for any kind of dispute, a defamation dispute, any other… employment contracts. And so if you're sexually harassed at work, and you've got an NDA in the context of the contract that you signed, when you started your job, then that covers it.

Jane Caro: So you sign in advance?

Jennfider Robinson: Sign up!

Jane Caro: Wouldn’t you have thought, there might be a reason, a little flag saying, don't work here.

Jennfider Robinson: Exactly. But I mean, we see examples in our practice, and we give a hypothetical example based on some of the things we've seen, where women have… one woman told… I'm going to do it hypothetically, though, so I don't identify anyone. But imagine a woman working in a financial firm, and she is suffering sexual harassment from her boss. And nobody really talks about it, and she's trying to manage it. And then, you know, he comes on to her. She calls him out and says, no, thank you, or no, very much, no thank you, and then decides to report it to HR and she says she felt like she was being put through a well oiled machine. And so she was, sort of, signed off, asked to sign a… you know, they had the agreement in place, she was asked to sign a nondisclosure agreement, and she signed it, thinking, I don't want to be here anymore. I want out. I just want to get on with my life and my career. And if this is what is involved, fine. Only later did she find out that the woman before her had had the same experience, a woman after her had the same experience, but even to be able to figure out that that was happening, they were breaching the terms of their own agreements. And so this firm was getting away with repeat incidents and placing women in an unsafe workplace, because of these contractual terms, but because of the silence around it, it's really difficult to get at it. And so I've had clients who were in that position, but aren't willing to put their head above the parapet and sue, because they don't want to be associated with what was done to them. And I understand that. And I think every woman should have the right to choose if they want to be public, or if they don't want to be public about it. But in order to litigate, it is expensive, the cost risk… so we talk about a case where a journalist wanted to publish a story about Philip Green, it's now in the public domain, so we can say his name. But he sought an injunction to try and stop a story about sexual harassment stories in the workplace. And the journalist tried to publish it. So journalists… if you sign an NDA, and you decide later, you want to go to a journalist, if the journalist then knows that you have an NDA, and still tries to report the story, they can be injuncted, because they're using information they know to be deemed confidential via contract. So it silences the woman, it silences any journalist from talking about it, and then if you go to court, that court case, just the pre-trial stage cost, I think, what was the like, in the millions of pounds. Who can afford? So you want to challenge your NDA? You're going to have to be potentially public about it, you might have anonymity until, you know, the injunctions overturned, because that could identify him too. But the expense is crazy. And women don't understand this when they sign these agreements. For a pittance as well, like the amount of money women are getting paid in settlements for sexual harassment is next to nothing. Next to nothing, when you compare it to what men are getting for defamation for having been accused of sexual harassment, it's just worlds apart, the system is skewed.

Jane Caro: So what do we do? How do we… you know, we've got, hey, 22 minutes left, you can fix this. What do we do? How do we stop powerful men using the law to circle the wagons and basically make this horrible #MeeToo thing, just go away? What do we do? What sort of thing… What can an ordinary woman do, who finds herself in that position?

Keina Yoshida: Well.

Jane Caro: You knew you were going to get this question.

Keina Yoshida: Let me start, rather than talk to the ordinary woman, I’d like to say, is what I want from this book, and from the two of us writing this book, is first to let people understand how the system works, and what the problem is. Because I think, unless you're an in-house lawyer, unless you're seeing these legal threats, and unless you understand how it's all… the silencing upon silencing is happening, then you don't understand, as Jen says, how much it is a part of a well oiled machine. So you know, we need first to be aware of the problem. We need to talk about it, and then we need to combat it that way. The second thing is, and this is very much for the lawyers and the judges, you know, Jen, and I started out because we wanted to intervene in a Supreme Court case in the UK called Stocker and Stocker. And this is about a woman Nicola Stocker, who goes on Facebook, and is talking to Mr. Stoker's new girlfriend. And essentially, she says, listen, this guy is dangerous, he tried to strangle me. And on the basis of that, not very many people saw it. I mean, his new girlfriend saw it. He sues her in defamation. He wins the case against her. And it takes her seven years to get the case to the Supreme Court, and she finally wins there. Now, in that case, the police were called, they saw marks around her neck. It was an accepted case. Both parties accepted what had happened. But the problem was that the trial judge had said, he tried to strangle her, means that he tried to kill her or he had the intention to kill her, and because she's alive, well then, you know, he didn't actually try to strangle her, under the legal dictionary definition, and therefore she defamed him. Real case, Mr. Justice Mitting, lovely man.

Jane Caro: Who we name and shame.

Keina Yoshida: And his very words were, I think, his intention was to silence or not to kill, and therefore, you know, the irony…

Jane Caro: So that's okay, then?

Keina Yoshida: The irony is just, you know, it's… and she had a restraining order in that case against him as well. And Jen and I wanted to intervene in the Supreme Court, we were instructed to do so by the civil liberties organisation Liberty, in the UK, the Supreme Court refused to hear us. And the arguments we would have made is that, the balancing exercise of that woman standing up there is not just his right to reputation, versus her right to free speech. It's also her right to equality, it's her right to dignity, and it's her right to live a life free from gender based violence, and all these other human rights that the ‘ordinary woman’, as you've called it, have, and that's what we need the courts to understand. And they've done so in Colombia, and they've done so in India, but they have not done it in the UK. I don't think they've done it in Australia. So, you know, we need our judges to understand violence against women, and we need lawyers to understand it as well and bring those into the civil courts.

Jane Caro: But in a way, how do we do that? Because, as you said, these are ancient tropes about the fact that women are liars, that women make these stories up, because somehow we're crazed with a desire for vengeance. Or, you know, what is it? Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned? And so, there is this image of the Medusa, the kind of destroyer of men. So how do we educate judges? How do we make our legal practitioners, many of whom come from the sorts of schools that Chanel Contos’ original exposé, and we are not free of regular, shall we say, scandals, in the press involving elite, I prefer to call them exclusive, and that's because they shut people out, exclusive boys schools, where an awful lot of them are going to have ambitions to grow up and be a barrister, a lawyer or a judge like Daddy, How do we change this mindset which accepts these ancient tropes? And particularly, just draw in here also the social media stuff. So I think you say in the book at one point, that it appears to be organised. That this social media it's manipulated, it's purposeful. It's not just, as I think Me Too genuinely was an outpouring of real, pent up miseries, secrecy and silencing. It's an organised - in some way, and by someone, I don't know who - response by powerful people to continue these sexist tropes, to turbocharge them. What do we do?

Jennifer Robinson: Well, I think there's a lot in that question.

Jane Caro: There is, sorry. It sort of wasn’t a question.

Jennifer Robinson: Let me address two of those points. So I guess, there's the issue about representation in our courts, and on the bench, and the issue of online trolling. And I'll speak to both of them.

Jane Caro: Yeah, I just kind of stuck them together cheekily.

Jennifer Robinson: But I think, so, one of the things we talked about in the book is that we need to have more women in the law, we need to have more women on the bench, we need to have more judges who understand what women's lived experiences are. And if you look at the bench, both in Australia and the UK, the two jurisdictions which we sort of focus on through the book, I think it's quite scary, actually. So we're approaching 50% women on the bench, and I'm delighted that we have a majority on our high court for the first time ever, as of this week, which is really exciting. It's not reflected in the lower courts, so we still have a lot of work to do. But if you look at the percentages of women going into the law and making it to the upper echelons, where we practise in the UK, 40% of women are Barristers. That drops to something around 20% of Senior Council or King's Council, as we call them in London now. In Australia, it's worse, or in New South Wales in this state, it's something like, something like, I can't remember the figure of how many barristers there are in practice, but, silks it drops down maybe 18%. And it drops down to like, 8% of Senior Counsel in this state are women. And that so it's, it's from the upper echelon. from Kings Counsel, Senior Counsel that you get appointed to the bench, and we just don't have the women coming through, to be appointed. In this state, the moment you get appointed silk you're almost tapped to go on the bench because there's such a demand. And we have to look at the structural issues to see why that's happening. At this rate, the Bar Council in the UK says that women will never take silk at the same rate as men. Never. That's terrifying. So I think we need to look at that. That's before we even get into the class questions about the old white boys, private school boys, on the bench.

Jane Caro: So many levels.

Jennifer Robinson: There's so many levels, but in terms of education, we do have, there is education for judges in this country. We have bench books on domestic violence which debunk these gender based violence myths and stereotypes. In criminal courts, juries have warned now, in sexual violence trials, about about ignoring any of the myths and stereotypes they hear in the context of the arguments.

Jane Caro: That didn't happen in the Amber Herd…

Jennifer Robinson: Precisely. So one of our recommendations is that, what we see in the civil justice system, we're seeing all these now civil cases, defamation cases being heard on gender based violence, but none of the same protections that we have in the criminal justice system exist. So in criminal cases, you'd get a warning. In the Depp case, they certainly got no warning about the tropes that have been rolled out in front of them. And so basically, Amber should never have been giving evidence live about sexual violence, that I mean, even live streaming a trial in our jurisdictions would be sort of countercultural, we would we don't do that here, but live streaming evidence of sexual violence… In the UK, during the defamation case, when she gave that evidence, the court was cleared. We applied to make sure that she had protection, so she didn't have to give that evidence in front of the world's media. And then she had to do it live streamed online, with thousands of comments from YouTube, people on YouTube commenting on every word she said, and every facial expression she shared. So some of these same protections need to be brought into the civil justice system. But it is a much bigger cultural problem, and we see it reflected in the online space.

Jane Caro: Absolutely we do. I think you make some really good points about the protection, because my impression is that many women, I mean, quite apart from the deformation, quite apart from the fear of, you know, losing everything they have, and all the social media and all of that, there's also the sense of being violated all over again, by the very system that is meant to be about distributing justice in a blind and fair way. Particularly Amber Heard, it seems to me, that's so traumatic, what has been done to her.

Jennifer Robinson: It’s horrific.

Jane Caro: And you also put other things in the book that really kind of horrified me. Situations where women are actually forced to apologise to their abuser, I just, I found that… and being cross examined by their abuser. There's a sense in which some of our court systems are designed not just to protect men, but to punish women who dare to speak up. How do we… I mean, it strikes me also, NDAs, I know you make an argument that there's reasons for them, and that can be used for good purposes. But if surely, there should be no place where if a crime has been committed, someone can say, oh, well, I'll never speak of this crime, because I've signed some document, given to me by a lawyer who I thought, I am naive, was meant to, you know, defend the law and report crime, if it's committed. Why are these things allowed to happen? Because, okay, the crime hasn't been proved, but there is an accusation. Surely there is a process when a crime is, you know, someone's accused of a crime. And it doesn't include, you're not allowed to say crime happened.

Keina Yoshida: So, there's a lot in that as well.

Jane Caro: I'm not a lawyer, why did you ask me to do this?

Keina Yoshida: Let's take that step by step. Okay. So I think I'll deal with one part of it, and then I think you should deal with Zelda’s story.

Jennifer Robinson: Yeah sure.

Keina Yoshida: Because that makes sense. Okay. So in terms of the first part of it, there's a criminal justice process. And it's really important that you have some really bad defamation cases, in our view, whereby the courts have said that you need to have a criminal conviction, in order for someone to say anything about their own experiences of abuse. So to use an example, there's a director of a domestic violence shelter, and she gives an interview on radio after she's accused of kidnapping a woman and her child who are in the domestic violence shelter. And she said, I didn't kidnap them, they came because they were fleeing from domestic violence. And the man sues her and actually brings a criminal prosecution against her and she gets a criminal conviction. And his argument was, because I have not been convicted of a domestic violence offence. It took 17 years for this woman to overturn her criminal conviction. And she only was able to overturn it because she was able to go to the European Court of Human Rights, because we're lucky enough to have a regional system of human rights in Europe. And in places like Latin America. It's not something you have here, so you should get one of those, as well. And it's really important. And the Court said in that case, no wait, that was in the public interest, and to have that level, like, needing a conviction in order to talk about a crime is a violation of free speech rights. So I think, one, that's one thing I'd like to say. The second thing I'd like to say is, a lot of women we spoke to said, I'm not interested in the criminal justice process, I'm not interested in proving if this is a crime or not, what I want is for this to stop, and what I want is to warn other women that this is happening. So I think it's important that we talk about the value of speech in and of itself, not just when it's a crime or not a crime.

Jennifer Robinson: I'll deal with the NDA point. So first and foremost, for anyone in the room who has signed an NDA, it cannot prevent you from going to the police and reporting a crime. And if you have an NDA that purports to try to do that it is unethical and unenforceable. So, unfortunately, though, there was a misperception around that. And we saw in the Weinstein NDAs, that they sailed very close to the wind and crossed the line of what was ethical or not. And there's now new guidance out advising lawyers, what they should have already known, which is you can't do that. So you can't stop someone from going to the police. And we saw that in the Bill Cosby case, for example, in the United States. So Andrea Constand was the one case that was prosecuted because she was the only person who spoke out who was within the statute of limitations in the United States. It was the one case that he was prosecuted for, and ultimately got off on appeal. But interestingly, before that criminal process started, when the women started speaking out, she spoke out and she talked about her experience and tweeted about it. And he sued her, saying… and he sued him on a couple of grounds. He sued her saying, I'm suing you, because you went, you talked to the police voluntarily, and your NDA prohibits that. And because you spoke publicly. And interestingly, the judge threw out the case on the police point, for the very same reasons I just explained, but allowed the rest of the case to continue. Now, that case didn't go all the way because I think Cosby and his lawyers, quite rightly, took the decision that probably wasn't a good look when you're about to be prosecuted for raping her, to be suing her, to try and silence her. So that case never was ultimately decided.

So you can't be prevented from going to the police, but you can be prevented from speaking to other people. And we've seen nondisclosure agreements which prevent you from, you can't tell your friends about it, and if your friends speak out about it, there's even been provisions non disparagement or disparagement clauses in these contracts, which means if anybody else who knows about it speaks about it, you have to disparage that person and deny that it happened. You sign an agreement saying that you won't speak badly of your perpetrator. So the terms of these agreements, I think, historically, and because they are themselves secret, it's not like there's a public register where once you sign an NDA, it goes and sits. And maybe I should mention a bit about Zelda. Zelda Perkins is this remarkable woman who worked with Harvey Weinstein, and she is the woman who blew the whistle on non disclosure agreements. So she worked for him. He sexually harassed her, he ended up sexually assaulting a junior woman who was working with her. And that was the point at which she said, enough is enough. I have put up with this too long myself, but I cannot facilitate him doing this to somebody else. So she and this woman quit. They wanted to hold him accountable. They went to lawyers, the lawyers said, no hope it’s Harvey Weinstein he is, you know, too powerful. They'll run you through the courts and make your life hell. But she insisted. And they offered an NDA. And she thought when she was signing the… you know, she thought she was just going to get a payout. And then at the last point of this settlement process, they were in these legal offices until 5am in the morning negotiating this stuff, it's, you know, she described it as a hostage like situation. And they were asked to sign an NDA, and she didn't really even know what it was. They had to write down every single person they had told what had happened. And they went into a schedule with the contract. She refused to name people. She just wrote categories of people around her who knew, because she was scared about what might happen to them. And she really believed that she wasn't allowed to tell anyone, but their NDA actually prevented them from, they weren't even allowed to talk to a lawyer or a therapist without the approval of Weinstein's lawyers. And so, I mean, these contracts. That's a particularly odious contract and we know, thanks to Zelda. But when Zelda spoke out she risked being sued. And the thing about when you're sued under a nondisclosure agreement, and you've been paid a settlement for, not just for what happened to you, but you're being paid for your silence, and so he can sue you, and not only sue you for damages for having revealed it, but sue you and sue you for the cost of suing you, but also take back everything that he paid you in the first place.

Jane Caro: It's coercive control, I would have thought of it, on an extreme level. Now we have some audience questions, and not much time left, but we might sneak a little bit, because I was told we could go a little bit over. This is from anonymous. In fact, they all are apart from Kya. I think this whole idea about ‘don't name anyone’, has really gotten into the audience. How do you respond to the argument of, ‘innocent until proven guilty’, and believe her? This is often something I hear coming up in casual conversations, what do you think, Keina?

Keina Yoshida: Well, I think, we talk about this in the book, and there is an important principle in the law, which is the presumption of innocence. And that is, a principle that is within the criminal justice system. So you're presumed innocent until you're proven guilty. The statement ‘believe her’, as Tarana Burke explains it, and also very eloquently, is that, it’s not ‘believe everything that somebody says’, it is, when people come forward with these allegations, these should be taken seriously. And what happens is, in fact, they're not taken seriously most of the time, and they haven't been in history. And women have faced obstacles at every single stage of investigation or prosecutorial decision, and in the trials themselves, so I agree with her. I think that's what ‘believe her’ or iota creo means. I don't think it's an attack on the presumption of innocence.

Jane Caro: The next question, Australia recently passed long overdue defamation law reforms, including the introduction of the Public Interest Defence. You mentioned public interest quite a lot in the book as being something that can be used to start to change these… and you mentioned it too Keina in a conversation, and the serious harm threshold. Will these reforms improve the plight for defamation defendants?

Jennifer Robinson: I believe they will. But it's the safety thing. So the serious harm threshold that's been introduced into the law here is the same threshold that was introduced into the UK as law in 2013. So we've actually been engaging with that test already through the defamation cases we deal with. In cases where you are reporting on gender based violence, you are always going to reach that threshold, and we talk about that in the book. It will be a very rare case where you're accusing someone of that kind of conduct, and a judge won't find that it will meet that threshold. An allegation of that nature does serious damage to a person's reputation, we accept that. So that threshold is not going to help in these kinds of cases. The public interest test is important. And so we talk a lot in the book about the importance of the public interest defence, because we say, as I said earlier, women's ability to be able to speak about their experience of abuse is a matter of public interest, and must be considered as such, in the law for the purposes of defamation. There's been a number of cases in the United Kingdom, which have recognized that. Not enough. So we have had judgments under the equivalent defence in the UK. The difficulty with the public interest defence is that this test is actually more difficult than you think. So what we talk about is like, you have to reasonably believe it's in the public interest. The statement you're making. And you have to have taken adequate steps to verify the information. Now, if you're a journalist, that test is actually quite strict. So for example, had that test existed in the law when Eryn-Jean Norville in the Geoffrey Rush case was going forward, the telegraph wouldn't have met that standard because of the nature of the way in which they conducted their journalism. So journalism goes on trial…

Jane Caro: Yeah.

Jennifer Robinson: In this defence. We haven't yet seen the public interest defence being used and deployed on behalf of a survivor. So what happens when you personally tell your story? So it hasn't actually come out in that context yet, and we say it ought to be used, and that should be a full defence.

Jane Caro: You do talk about how if truth is the defence, the woman goes on trial. If public interest is the defence, journalism goes on trial. So that's an interesting…

Jennifer Robinson: So journalists don't do their job. They don't properly investigate the facts. They don't go to the perpetrator, or the alleged perpetrator, to ask for their side of the story. They don't include that. If the judge disagrees with their assessment of credibility, there's a whole range of things. And so I think, here in Australia, we are fast becoming the liable capital of the world. London is losing its lustre. So we are notoriously pro claimant. We have incredibly high damage payouts, incredibly high legal costs, it's very expensive. So I hope that this law reform goes some way to mitigating that. Because in the, sort of, you know, we get so few judgments that go all the way to trial and judgments, you get so few reasoned judgments. But I'm hoping that in that back and forth that we experience in the newsroom with journalists, that here will be a more robust approach taken because we have the availability of that defence. But what that will look like, we have to wait to see how the cases play out.

Jane Caro: We are at the end of our time, but there is one last one I just like to very quickly go through. More women on the bench won't necessarily change the application of outdoor dated laws and processes. What are the main factors that can inform progressive law reform in this area? Must this be driven by political will? Or are there other ways? And I did want to bring up in the context of more women in senior positions, the accusations about a judge in Australia, not that long ago, only actually got taken seriously because we had a female high court judge. You know, Chief Justice. For the first time Susan Fraser, I'm talking about, I will say her name. Judge Dyson, the case about the accusations there…

Jennifer Robinson: Dyson Heydon

Jane Caro: Yep. Dyson Heydon. That's it, sorry, Dyson Heydon. I don’t know what's wrong with me and names tonight. But um, so that's an example of where having a woman in a position of power actually meant something changed. Something fundamental changed.

Jennifer Robinson: Well, I don't think it was just having a woman in a position of power. Personally, if you don't mind me addressing it, it's because so many women came forward.

Jane Caro: Yeah. True. And, that… in a way… how many more women is… I mean, Bill Cosby had 60!

Jennifer Robinson: Exactly. I mean, and that's why we ended up calling the book this, because it became, we talked about it, it comes up in so many contexts. When we were writing this book, we tried for ages to find a title. And I have to attribute it to Kelly Fagan, our publisher who chose the title, after us ranting about this. But it comes up so much so often. So we're, you know, we're legaling a story. How many more women have to accuse this man before the journalist will publish this story? How many more women have to speak about Dyson Heydon before the High Court actually investigated? It took a few of them to get together to get that done. And so that's again, why we talk about why it's so important for one woman to be able to speak, because it often encourages more women to come forward. And sadly, despite feminist’s fights to ensure that one woman's testimony is enough in a criminal context, we're increasingly seeing, I think, through the way that journalism is practiced, the way these defamation cases have been heard, that one woman's testimony is not enough. So how many more women? Have to accuse, before we believe her?

Jane Caro: Yeah. Them. Us. Well, I think we really have reached the end of our time now with these two extraordinary legal minds, brilliant writers, awesome, powerful, feminists and advocates for women and for survivors. I think this is such an important fight, we cannot allow ourselves and anyone who has been abused, whatever their gender, to be silenced in this way. Because, to my mind, silence makes the world safer for those who would misuse their power, and the rest of us, more vulnerable. When women or any survivor speaks up, they change that balance, just a little bit, which perhaps is why we see the viciousness, the organised trolling, the horrendous use of what ought to be good mechanisms, legal mechanisms, in such a brutal and raw kind of way, because we are shifting that dial. Sometimes they say, the more they hate you, the more effective you're being. I'm worried for you.

Jennifer Robinson: Look at my Twitter trolling.

Jane Caro: You might get a bit of crap, but just remember that everybody in this room, I'm speaking for you. Sod you if you don't agree. That everyone in this room loves and supports what you're doing. Thank you.

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. This event was presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas, UNSW Law and Justice and Sydney Writers Festival and was supported by Allen and Unwin. For more information visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

-

1/5

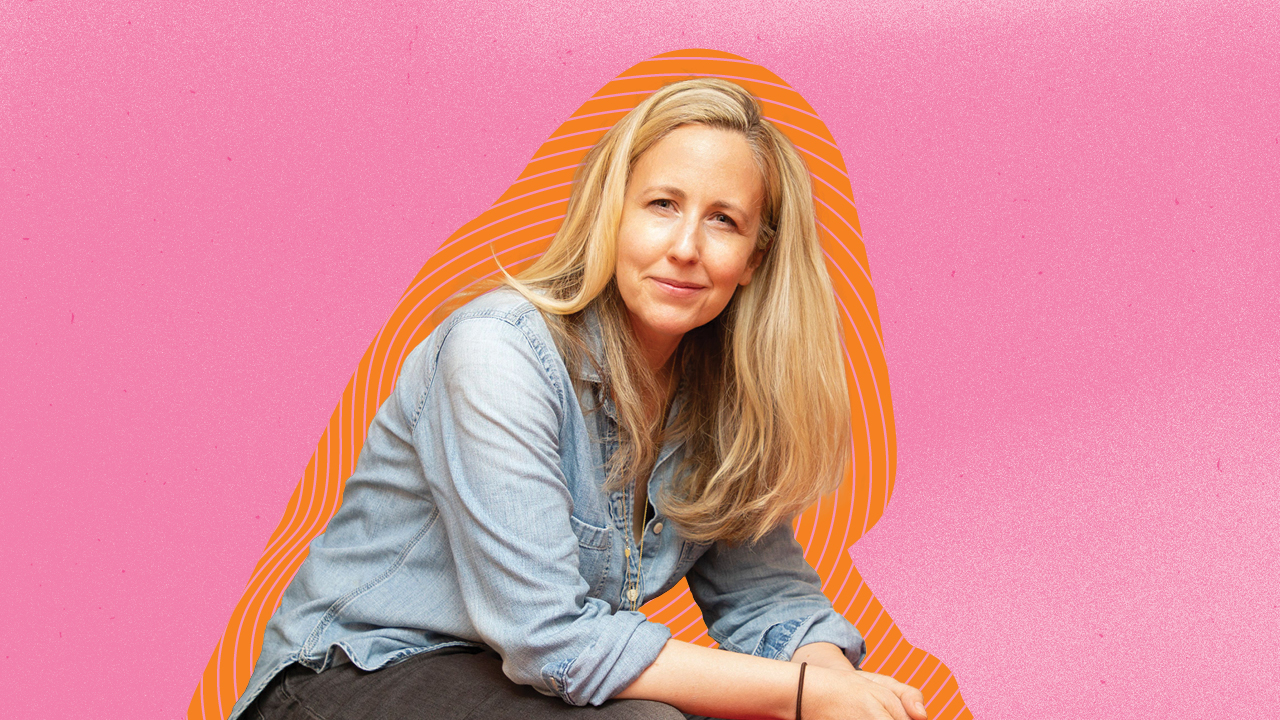

Jennifer Robinson

-

2/5

Keina Yoshida

-

3/5

Jane Caro

-

4/5

Justine Nolan

-

5/5

Jennifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida live in conversation at UNSW Sydney

Jennifer Robinson

Jennifer Robinson is a human rights lawyer and Barrister at Doughty Street Chambers in London. Jen has been instructed in domestic and international cases involving media law, public law and international law. She advises media organisations, journalists, whistle-blowers and high-profile individuals on all aspects of media law and reputation management. She has also been instructed in human rights related judicial review cases and has given expert evidence in Parliament and at the United Nations.

Jen advises individual and state clients on a wide range of international law issues, has appeared before the International Court of Justice and regularly engages with UN Special Mechanisms. Many of her cases and clients are high-profile and involve novel cross-jurisdictional and comparative law issues. Jen has also acted in judicial review proceedings before the Court of Appeal and High Court, including challenges to government policies related to climate change, fracking and the treatment of refugees.

Jennifer has acted in key free speech and freedom of information cases for clients such as the New York Times and Bloomberg. She is a member of the legal team for WikiLeaks and Julian Assange, having acted for Assange in extradition proceedings, advised WikiLeaks during Cablegate and worked with the Center for Constitutional Rights on United States v Bradley Manning. For more than a decade she has been involved in advocacy related to self-determination and human rights in West Papua. In 2008 the UK Attorney General recognised Jennifer as a National Pro Bono Hero. Jennifer was educated at the Australian National University and the University of Oxford where she was a Rhodes scholar. She writes for publications such as the Sydney Morning Herald and Al Jazeera.

Year of call: 2016 (2006 - Supreme Court of NSW, Australia)

Keina Yoshida

Dr Keina Yoshida is a human rights lawyer, media lawyer and feminist. Keina is a lawyer with the Center for Reproductive Rights and was a practicing human rights barrister at Doughty Street Chambers where they are currently an associate tenant. Keina has acted in key human rights cases including on LGBTI rights, and women ́s rights. Keina is a visiting fellow at the Center for Women, Peace and Security, at the London School of Economics.

Jane Caro (Chairperson)

Jane Caro AM is a Walkley Award-winning Australian columnist, author, novelist, broadcaster, advertising writer, documentary maker, feminist and social commentator. Jane appears frequently on Q&A, The Drum and Sunrise. She has created and presented five documentary series for ABC's Compass. She and Catherine Fox present a popular podcast with Podcast One, Austereo Women With Clout. She writes regular columns in Sunday Life. She has published twelve books, including Just a Girl, Just a Queen and Just Flesh & Blood, a young adult trilogy about the life of Elizabeth Tudor, and the memoir Plain Speaking Jane. She created and edited Unbreakable which featured stories women writers had never told before and was published just before the Harvey Weinstein revelations. Her most recent non-fiction work is Accidental Feminists, about the fate of women over 50.

Justine Nolan (Introduction)

Justine Nolan is the Director of the Australian Human Rights Institute and a Professor in the Faculty of Law & Justice at UNSW Sydney. She has published widely on business and human rights and her latest book, Addressing Modern Slavery (2019) (with M. Boersma) examines how consumers, business and government are both part of the problem and the solution in curbing modern slavery in global supply chains. She advises companies, NGOs and governments on these issues and is a member of the Australian Government’s Expert Advisory Body on Modern Slavery. Justine has practiced as a private sector and international human rights lawyer. She is the Executive Editor of the Australian Journal of Human Rights, a member of the Editorial Board of the Business and Human Rights Journal and is a Visiting Scholar at NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights.